Dover flying sites

Note: This map only gives the location of Dover within the UK.

Pictures by the author unless specified.

DOVER see also DOVER COASTGUARD STATION

DOVER see also GUSTON ROAD

DOVER see also SWINGATE DOWN

DOVER AIR PORT see SWINGATE DOWN

DOVER see also WHITFIELD

DOVER: Temporary balloon launch site

Period of operation: 7th January 1785

NOTES: On this date the Frenchman Jean-Pierre François Blanchard, (a scientist and inventor), and the American Dr John Jeffries made the first successful aerial crossing of the English Channel in a hydrogen filled balloon landing near Calais. It seems the balloon sprang a leak, (early balloons did leak), but it could have been a temperature related event of course. Literally everything had to be jettisoned including most of their clothing to prevent a ditching. Such an event would almost certainly have been quickly fatal due to hypothermia unless quickly rescued and it seems they took no precautions about having some boats available. Bearing in mind this was in January, I bet they wished, (as at least one author mistakenly maintains?), that this was a hot-air balloon, when they could have at least warmed their hands.

In 2010 I came across an account of the proceedings in Flying’s Strangest Moments by John Harding from which I think this excerpt is well worth quoting. I trust you will be as amused as I was as Blanchard was obviously quite a character. His first attempt at building an aerial vehicle was an utter failure, but: “The achievements of the Montgolfier brothers then inspired him to try a combination of the lifting power of the balloon with flapping wings for propulsion. His highly original contraption took its first flight on 2 March 1784.” It is perhaps worth mentioning that the first ‘human’ passenger flight in a Montgolfier balloon took place in November 1783 although on the 27th of August 1783 the French physicist Jacques Charles had ‘flown’ a large unmanned hydrogen filled balloon across Paris.

But, back to the story: “Like many inventors, Blanchard depended on the generosity of benefactors, although he was often loath to acknowledge them. In 1784, an American doctor named Jeffries, who had an interest in meteorology, offered to pay Blanchard the costs of taking his new balloon across the English Channel to France. Such generosity was to be no guarantee that the doctor would actually be able to take part in the flight, and share the glory, however! Blanchard insisted on travelling alone.”

“In December 1784, he took the balloon to Dover, then barricaded himself inside Dover Castle, locking Jeffries out. Jeffries recruited a squad of sailors and then enlisted the services of the castle governor to negotiate an agreement between the two men. To no avail, however, as Blanchard persisted in trying to leave his sponsor behind.” I do hope this story is true, despite it coming very close to becoming the script for a Monty Python sketch!

It gets better: “When the inflated balloon (carrying a gondola packed with Blanchard’s own steering gear, consisting of wing paddles and a hand-turned fan to act as a propeller) was tested for lift-off with the two men aboard, it was found to be too heavy. Blanchard again suggested he should make the flight alone, but Jeffries was suspicious enough to inspect the Frenchman’s clothing – to find he was wearing a belt under his coat, fitted with a set of heavy lead weights!”

“The flight was postponed. At last, however, on the 7 January 1785, with both men on board, the balloon took off in good conditions from the cliffs of Dover, heading towards Boulogne. They carried only 30 pounds of ballast with Blanchard still doubtful of the balloon’s capacity to carry two passengers. Apparently, Dr Jeffries had only been permitted to go on the understanding that he would jump overboard if necessary!”

“Although the pair had eventually dropped all their ballast overboard with the French coast still some miles away, the balloon never managed to climb to a safe altitude, and it seemed they would come down in the sea. Frantically, the two men began jettisoning everything they could. First to go were the extragavent gondola decorations, followed by Blanchard’s steering gear.” Why was it I wonder, that it was conceived as being absolutely essential that nigh on every balloon ascent HAD to be adorned with heavy and expensive decorations?

“Then followed the anchors and the two men’s coats, followed by their trousers! The remedy worked and the balloon climbed to a safe height, finally arriving at the French coast at 3 p.m. to land just outside Calais. On the following day a splendid fete was celebrated in their honour at Calais. Blanchard was presented with the freedom of the city in a golden casket. The municipal body purchased the balloon, with the intention of placing it in one of the churches as a memorial of the experiment, and also resolved to erect a marble monument on the spot where the famous aeronauts landed.”

FINDING THE LOCATION

As is so often the case, those recording aviation history rarely think to establish the place from which these events happened. For example, this is the case when Henry Dale, in his book Early Flying Machines, describes the ascent made on the 5th September 1862 by James Glaisher and Henry Coxwell. Incredible though it might seem, they are attributed to have ascended to an estimated 37,000ft (11,300m). “…higher than anyone had ever been before. At 29,000 feet (8840 m) they were experiencing paralysis and partial loss of consciousness, but continued to ascend as their plan was to go as high as possible. The account of the flight above this level is sketchy as the two seem to have been lapsing in and out of consciousness; fortunately Coxwell managed to pull the valve line with his teeth (his hands being paralysed) to release gas and descend, whereupon they recovered fully. They also released pigeons at different altitudes, some of which survived, while others perished.”

Two things here: Does anybody now know where this ascent was made? Also, has anybody written an account of how pigeons featured in aviation history up to, and including, WW2? I reckon it is very interesting to learn, again from Early Flying Machines by Henry Dale, that the first aerial crossing of the Adriatic occurred in 1804 and the first aerial crossing of the Alps was in 1849. It seems that today we tend to be too fixated on fixed wing and powered aerial history, the history of ballooning taking second place, along with early gliding achievements.

ANOTHER ATTEMPT

Another attempt to fly a balloon from France to England, also in 1785 by Pilâtre de Rozier, accompanied by Pierre-Ange Romain, ended in tragedy when their hydrogen filled part of the combined ‘double-bubble’ hot-air balloon caught fire. I suspect that few, (I certainly did not before starting this research), realise today just how early and quickly ballooning ‘took off’. Manned balloons flew, in 1784, from Austria, Great Britain, Italy and Spain. In 1785 from Belgium, Germany and The Netherlands. By 1788 Switzerland was added and during 1789 flights were made in Poland and Austro-Hungary. The USA was way behind, perhaps quite understandably, with their first balloon flights taking place in 1793.

DOVER: Man-carrying kite landing area

Period of operation: One day in 1903

NOTES: I will fully understand if you think I’ve now lost the plot here but please bear with me. Around the turn of the 20th century the British War Department only saw two possibilities for airborne machines, balloons and kites, and both primarily for battlefield observation duties. One of the best exponents of man-carrying kites was Samuel Franklin Cody, the flamboyant American leader of a Wild West show that toured the UK and who later became the first ‘official’ pilot to perform a powered flight in the UK at LAFFINS PLAIN or FARNBOROUGH, (see FARNBOROUGH for more info). I strikes me as being very interesting to find, or so it appears, that such a 'large character' and self-publicist as Cody never claimed to make the first UK flight.

It would appear true, especially given his flair for publicity, that in December 1903 Mr Cody was towed across the English Channel to DOVER whilst controlling three kites to support his weight! Today of course we regard gliders and kites as being vastly different affairs but that simply wasn’t the case in those days. In fact it seems pretty hard to differentiate between these devices and the eventual fitting of an engine to either type of aircraft goes a long way to explaining how early fixed wing aviation evolved. It’s not for nothing that one of the earliest and successful Bristol, (or rather British and Colonial Aeroplane Company), designs was called the ‘Boxkite’. I wonder where Mr Cody actually landed - on the pebble beach where the Dover harbour complex now exists perhaps?

Another story has come about during my research. In the early1900s, (presumably before 1903?), Cody set about towing himself, (in a canoe he’d designed and built), across the English Channel from France, behind one of his kites. Indeed, a photograph exists of him having arrived in Dover sitting in his canoe. Unfortunately the picture I saw wasn’t dated.

However, it does seem that eventually these cross-Channel and other publicity stunts did finally awaken the interest of the War Office to the possibility of using man-carrying kites for reconnaissance duties. The Royal Navy invited him to Portsmouth for trials of a kite towed behind a warship. Apparently his son Leon was the first to fly and took a photograph of warships from 800ft. Several officers then had a go and commented on the potential the method had for gunnery ranging. In those years the Army too invited Cody to Salisbury Plain for trials.

THE 'MAN-LIFTER' KITE

In 1901 Cody patented his ‘Man-Lifter’ kite with a wing-warping arrangement to assist lateral control. Wing warping was by then a well known technique. Later, the incredibly greedy, small-minded and avaricious Wright brothers tried to patent the ‘aeroplane’ idea as being their own. The more I discover about these two the more astonished I have become. They really were disgraceful in many respects, often acting without principle and prepared to lie and cheat throughout their flying career if many accounts are to be believed. They certainly weren’t the first to ‘fly’ in the correct sense of the word and they cheated on that claim too. In 1903 their famous 'First flight' was only a hop and it is now beyond doubt other machines had performed similar 'hops' before 1903.

It is such a shame they behaved as unscrupulous rogues, although they would be mortified to be described in such terms – but deeds speak louder than words? Attempting for years to patent ‘The Aeroplane’ as their idea! This now seems doubly ironic as there appears little doubt that they did indeed perform the first flights; albiet in relative secrecy near their home in Dayton, Ohio. To explain; To make a ‘flight’ this requires a pilot to fly around a circuit exercising the aircraft in all three axis. Indeed, the same rule applies even today for a ‘first solo’. It certainly would appear from various sources that back in Dayton, Ohio the brothers the brothers were the first to fly controlled flight circuits.

And, they did indeed, (as all the pilots at the Le Mans and first Reims Meetings in France agreed), design and build the best ‘all round’ practical aeroplane. I think this should be recorded in history as their ‘TRUE’ claim to fame.

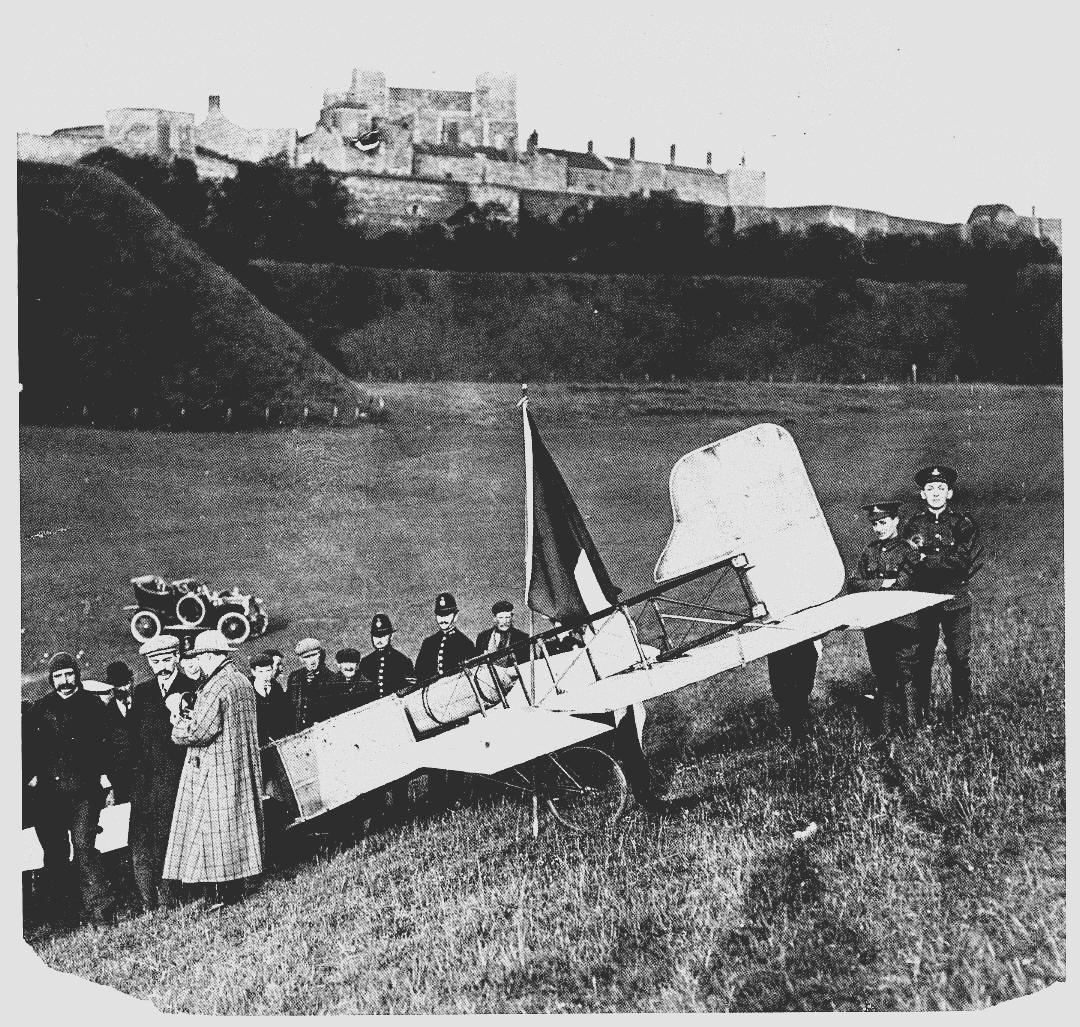

BLÉRIOT LANDS (FIRST CROSS CHANNEL FLIGHT)

Note: First picture by the author - NORTHFALL MEADOW is in the dip just beyond Dover Castle in the top left hand corner.

The second picture is a detail from the front cover of a music sheet for the Marche Aérrenne by Rodolphe Berger, composed in 1909.

The third picture was scanned from The Story Of Aircraft by David Charles, published in 1974.

The fourth picture: This was obtained from Google Earth ©

BLÉRIOT AT DOVER: Temporary landing site (aka NORTHFALL MEADOW)

Location: Near to and just north east of Dover Castle.

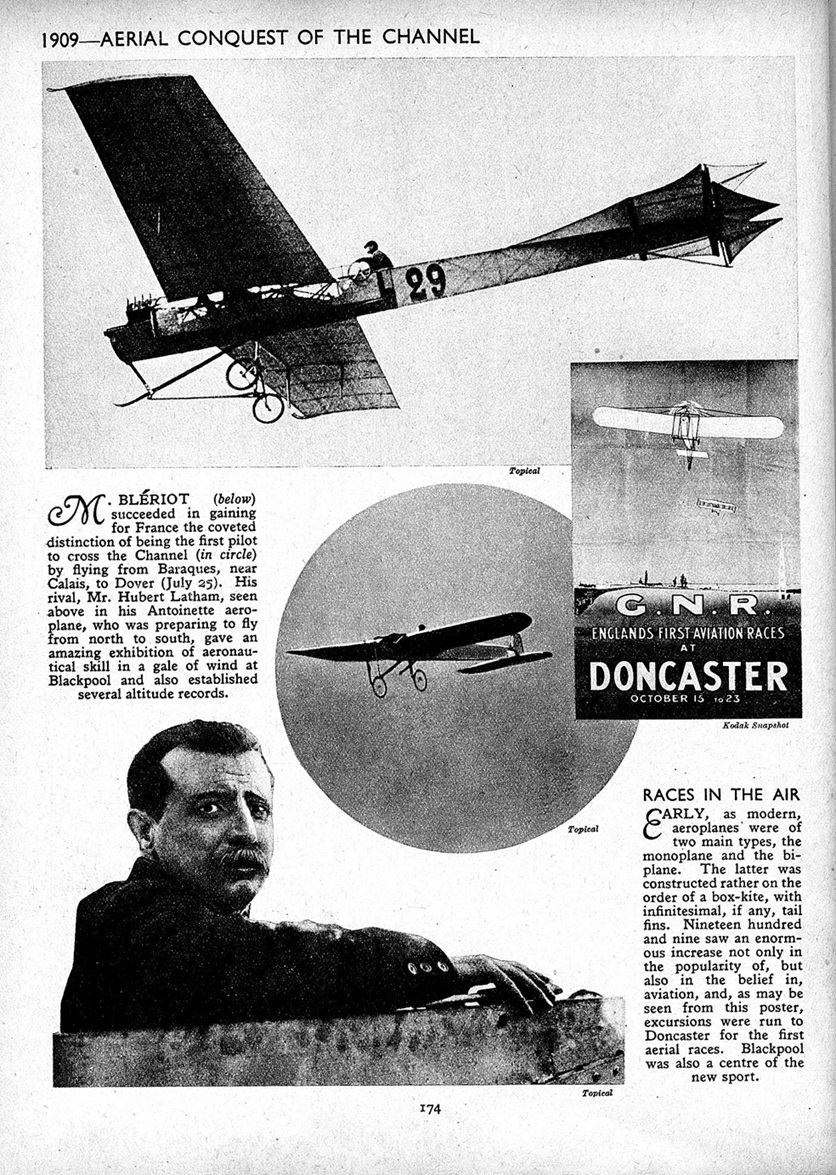

NOTES: At 05.18 on the 25th July 1909 Louis Blériot flying his Type XI monoplane was the first person to successfully fly across the English Channel in a fixed wing aeroplane although he did make a crash landing damaging his machine. In fact landings were not Blériot’s strong point. Two French journalists were in NORTHFALL MEADOW since dawn to wave a large French tricolore flag to mark the spot. The site had already been selected as it marks a low ‘gap’ in the cliffs as there is still some doubt if the 25hp Blériot XI could climb high enough to land on top of the cliffs.

In those days flying at an altitude of 50 metres (about 165ft) was considered a reasonably high altitude and later that year at the historic Reims Aviation Meeting the altitude prize went to Hubert Latham flying an Antoinette IV to 155 metres (508ft). This was brought home around seventy or so years later when Tony Biannchi at WYCOMBE AIR PARK received a commission to build an exact replica which resolutely refused to take-off. Every detail was checked and double-checked but still the machine failed to lift-off. Then somebody had the bright idea to ask, “What is the service ceiling of a Blériot XI?” Whatever it is, it was below the 520ft above sea level that WYCOMBE AIR PARK lies at!

The Blériot XI had minimal if any instrumentation and certainly wasn’t equipped with a compass and at some point he became somewhat lost taking a more northerly heading until he spotted the ‘white cliffs’ in the haze and turned westward. In fact three pilots and crews were assembled around Calais to attempt the crossing. Hubert Latham had made an attempt in a Antoinette IV on the 19th but he was forced to ditch after his engine failed. The ‘ex-pat’ Russian Charles Compte de Lambert was also in contention with a Wright biplane development of the ‘Flyer’.

Today we have the popular myth of Blériot making his way across the Channel utterly alone but this is not exactly true. The French Navy had sent two destroyers for the attempts and the English had several smaller boats on hand to assist if the flyer had difficulties. It is said that Latham didn’t even get wet after he ditched being picked up shortly afterwards by one of the French destroyers. Marconi had set up a radio station on the cliffs near Dover to send weather reports to France. The first known use of radio to aid pilots.

Blériot was based in a field at Les Baraques whereas Latham was based at Sangatte and it is said the noise of the Anzani engine of Blériot passing over nearby woke Hubert Latham, who, knowing the weather would be suitable had left instructions to have his aircraft prepared before dawn. It is said his crew overslept! If they hadn’t the history books could well be different because, and if anything, his Antoinette was, on paper at least, the better machine with which to attempt the crossing.

WORLD SHATTERING NEWS

Perhaps it is difficult today to realise what a truly earth-shattering achievement that 37 minute flight represented at the time. It was at the very least the equivalent of Yugi Gagarin first orbiting the earth in space! It triggered a truly massive outbreak of aviation ‘fever’ in France and within two days Blériot had more than a hundred orders for the Type XI. In Britain with its Empire and the most powerful Navy in the world the significance that it could no longer be defended by the Navy alone did not go unnoticed.

Today very few have heard of NORTHFALL MEADOW and LES BARAQUES but these sites are in fact two of the world’s most significant flying sites. Easily equivalent to Cape Canaveral! But, as anybody who starts to investigate aviation history, (or any other sort of history), soon realises, the facts soon get distorted to suit other peoples agendas. I can highly recommend ‘Taking Flight’ by Richard P Hallion if you wish to further your knowledge of the early years of aviation history, and quite a story he tells too.

It appears that on the 27th July 1929 eleven aircraft from 41 Squadron based at NORTHOLT escorted Louis Blériot from Calais to Dover to commemorate the 20th anniversary of his historic flight, although I doubt he was still flying? Can anybody tell more of this event?

A PICTURE PAGE

We have Mr Ed Whitaker to thank for loaning me his copy of 'The Pageant of the Century' published around the mid 1930s, obtained at a car boot sale. I have placed it here simply because it mainly features the two main contenders for being the first to fly across the English Channel.

DOVER: Temporary airfield (BROADLEES)

Location: Broadlees (Can anybody tell us where this was?)

NOTES: On the 2nd June 1910 The Honourable C S Rolls (of Rolls-Royce fame) took-off in his Short-Wright type from it’s launching rail near to his shed at BROADLEES at 18.30 and completed a return flight to France, (making landfall at Sangatte near Calais, without landing but dropping a letter to the Aero Club de France), the first aviator to do so - making a return non-stop flight that is; and not dropping something from the air! He landed back at BROADLEES, after circling Dover Castle at 20.06. Just over a month later on the 11th July he was killed at the aviation meeting in BOURNEMOUTH/SOUTHBORNE when his aircraft fell apart in mid-air - thus becoming the first British person to die in an aircraft accident.

On the 2nd June 2010 Paul Anderson flying the Cessna 150 G-BJOV set off to celebrate Rolls achievement which today is largely forgotten, except he took off at 18.30 from WALDERSHARE PARK gliding site near Dover and landed at Calais-Dunkerque airport to post his letter to the Aero Club de France, (dropping items from aircraft is not allowed today, unless you belong to the military or a parachute club), reminding them that C S Rolls was also a member of their Club. Even so he landed back at WALDERSHARE PARK at 19.38, (also circling Dover Castle), and making the point that, “….this was one occasion where a Cessna 150 outperformed another aircraft.” A rare occasion indeed! (Sorry, it’s a pilot joke).

ANOTHER RARE STORY

It is pushing the limits to say this concerns DOVER, but where else could I put it? In his fabulous book, British Aviation - The Pioneer Years, first published in 1967, Harald Penrose has this tale to tell. It concerns the introduction Tommy Sopwith had to aeroplanes, having previously been mostly concerned with ballooning - and racing in yachts.

"Ballooning had been his introduction to the air, but his urge to fly aeroplanes began in the summer of 1910, when he and his friend Bill Eyre, with Fred Sigrist as engineer-crew, put into Dover Harbour after a slow Channel crossing. They learned that an American architect of Spanish descent, Johnnie Moissant, had landed his Blériot in a field about 7 miles from Dover after crossing the Channel for the first time with a passenger - his hefty mechanic Albert Filieux. Sopwith and his friends soon located them, and were enchanted with their first sight of the airy grace of a flying machine and amazed that it could carry so heavy a passenger."

For my part I am amazed that Sopwith and his friends found Moissant and Filieux so easily, some seven miles away. How did they do this? But, we need to remember that in those days the 'word of mouth' method was remarkably effective. Probably more effective than having mobile phones and GPS etc.

"Sopwith decided there and then that he must turn from ballooning to aeroplanes, and within a few days was at Brooklands, where Mrs. Hilda V. Hewlett, the estranged wife of the author, Maurice Hewlett, had started a company with a Frenchman called Gustav Blondeau to operate a Henry Farman for tuition and joy rides. Sopwith paid a fiver and was taken for a sedate cruise of two circuits of Brooklands, only to confirm that he 'was terribly bitten by the aviation bug'.

The rest, as they say, is history.

DOVER: Temporary airfield

NOTES: From the 5th December 1910 Cecil Grace also decided to attempt a both ways crossing of the English Channel but this time actually landing in France, but abandoned the attempt. The next attempt on the 18th was abandoned due to bad weather but on the 22nd he flew to Les Baraques in France where Blériot took-off from. On the way back he encountered fog, (perhaps even haze?) and was heard still flying near the North Goodwin lightship. Shortly after he and his aeroplane disappeared without trace.

DOVER: WHITFIELD (See seperate listing with maps and pictures)

Period of operation: 3rd July 1911 for arrivals, no date for the return crossing?

NOTES: The European Circuit race, (held during June and July), included crossing to England, the initial landing site being DOVER, followed by HENDON via SHOREHAM. The race was divided into stages: Paris to Liége, Liége to Spa-Liége, (presumably near or where the present day F1 race circuit is situated?), Spa-Liége to Utrecht, Utrecht to Brussels, Brussels to Rubaix, Rubaix to Calais, Calais to Dover, Dover to London (HENDON via SHOREHAM), London to Dover (via SHOREHAM), Dover to Calais, Calais to Paris. A total of 1025 miles.

Unlike the previous two races in 1911, the Paris to Madrid race and the Paris to Turin and Rome Race, this race had “…no very difficult country to fly over.” And, “…the airmen were guided by patrol boats when crossing the Channel.” We need to remember of course that these most fantastic races were taking place just two years after Blériot first crossed the Channel.

To quote C C Turner, “They were allowed to change their machines at any of the stopping places. The prizes, which amounted to nearly £20,000, were so divided that each competitor had a good chance of recouping himself for expenses by doing well in one of the stages. Of the sixty entrants, thirty-eight started, and nine completed within the stipulated time, six of them on July 7, the other three on July 8. From the start until the crossing of the Channel the weather was very bad, and the airmen took big risks.”

“Dover waited up all night, and was well rewarded, for the eleven airmen arrived within a period of three-quarters of an hour. Védrines arrived at 4.38 a.m.” The entire account is stuffed full of nail-biting drama, thrilling deeds, heroic endeavour and, of course, tragedy. But, who today knows about this? Very few I suspect?

For the purposes of this 'Guide', discovering UK flying sites, other recorded landing sites used by these airmen for a variety of reasons during this stage of the race include; DORKING, EASTBOURNE and NEWHAVEN.

And, there are other elements to the story. During a lull in the arrivals at HENDON Mr C C Paterson gave exhibition flights in a “Baby” Grahame-White biplane. Lieut. Barrington-Kennet, of the Coldstream Guards, a member of the Army Air Battalion, also gave a fine display of flying on a military Bristol biplane. On flying his machine from FARNBOROUGH to HENDON his petrol feed-pipe went wrong when he was over UXBRIDGE, and he landed in a space so confined that he was said to have “alighted on a tablecloth”.

DOVER: WHITFIELD (See also seperate listing with maps and photos)

NOTES: On the 16th April 1912, the American aviatrix Harriet Quimby, (the first woman to gain a U.S. pilot’s certificate), took off from Dover to fly to Calais in her 50hp Blériot monoplane. She presumably got lost in the marginal weather and/or fog that day and actually landed on the beach at Hardelot-Plage about 25miles (40km) southwest, (having passed fairly close to Boulogne), although perhaps she didn’t see it due to the fog or haze?

She thereby became the first woman to fly across the English Channel although the achievement was barely recognised by the press either in the UK or the USA. I have seen it claimed, (more than once), that the reason for this being that the Titanic sank on the night of the 14th/15th April! So, whilst correct, certainly understandable in the circumstances.

Several people, including pilots, tried to dissuade her from undertaking such a foolhardy task and it is reported that the then very famous Gustav Hamel volunteered to dress himself in her clothing and perform the flight for her – landing at a remote location where they could swap places. Needless to say she quite rightly rejected the offer.

Some say that Hamel was also keen to get into Harriet’s bloomers for less honourable purposes? Of interest I think, she did apparently take Hamel’s advice to take a compass. Without much doubt this saved her life, but quite possibly only just? I’ll state my reasoning: As we now know installing a compass in an aeroplane without it being calibrated and compensated is pretty much a waste of time, and of course might well partly explain why she ended up roughly 50° west of her intended destination.

She was very foolhardy indeed to even attempt the crossing and was very lucky to survive if reports can be relied upon. For example one account states, “…the craft sprang forward and took off at 5.30 a.m. She gained height and then rendezvoused with the film cameras over Dover Castle. The day was misty and she could no more see them than they could photograph her. She realised she would have to make the flight by compass, while timing her progress, hoping the weather would clear over the Channel. It didn’t but, as she neared what she hoped was the coast, rifts at last appeared in the mist and the morning sun began to shine through, down on ‘the white and sandy shores of France ”

It is possible to reconstruct her flight to some extent. Without much doubt she had to fly pretty low in these conditions, perhaps as low as 100ft or even less to both keep in sight of the sea surface and maintain some sort of horizon. To both fly the aeroplane and navigate by compass in such conditions is a very demanding task, which might explain why she took so long to figure out she was heading too far west? (My note: To navigate using a compass alone is far from easy, which is why the gyroscopic D. I. - (Direction Indicator) was invented), and also Harriet had had no practise in using a compass for navigation. In fact it seems she had little experience of flying the Blériot which was hardly a stable machine. We don’t know if the compass had been fixed to the airframe or was hand-held. And on top of this a magnetic compass points to magnetic north and you then have take your heading including 'variation' and other factors. In modern aircraft this is relatively easy as the actual heading is displayed numerically in a ‘window’, and the compass readings are 'compensated for' when being calibrated. But, it still takes quite a bit of practise before you can quickly visualise the ‘angle’ or direction within a sweep of 360°.

A BIT OF ANALYSIS

The French coast east of Calais runs ENE to WSW and Calais from Dover is roughly on a bearing of 110°. West of Calais the coast turns SW to Cap Griz-Nez which is on a bearing of 150° from Dover. As she didn’t see Cap Griz Nez she had already veered west by at least 40° after leaving Dover, and Dover to Cap Griz-Nez is only 18nm. Beyond Cap Griz-Nez the coast runs close to South for 40nm. Therefore she was by now heading roughly south to south-east, (heading south-east would have been the sensible thing to do at any time since leaving Dover), and spotted land on her left side thereby having already corrected her huge curving course deviation westward to quite a large extent. Possibly through 90° and perhaps more? We will never know how far she flew west of Cap Gris Nez before turning, and indeed, she might well have done this in increments whilst she got to grips with this new fangled device rather than a sudden dramatic change of heading.

What I cannot find out is the range of her Blériot, presumably a XI? This makes a big difference as to the outcome scenario. If it was in excess of 110km (70 miles) and if she had managed to maintain a southerly track, she would have made landfall somewhere NE of Dieppe. If a lesser range applies she could well have ditched and perished. It would appear simply fortuitous that a clearing of the mist/fog near Hardelot enabled her to land.

This said, Harriet was a very cool customer. As one report states: “…she was freezing so she landed, to be met by a crowd of fishermen. She had done it – but as she knew, she hadn’t really done anything until the press arrived, cold-foot from Calais and off the Daily Mirror tug which had been shadowing her, to record the event in words and pictures.” This is yet another example of very sloppy journalism. The Daily Mirror tug had obviously been employed, and suitablystationed along the Dover to Calais route. It would not and could not have been ‘shadowing’ the actual flight path. I wonder how many hours it took before the press, or at least the front runners, eventually arrived? Especially in those days!

She died a few months later back in the USA when, at an air meeting being held in Boston, for some never explained reason, her Blériot suddenly pitched violently down in flight ejecting both her and her passenger. She has been criticised for not making sure the seat belts weren’t fastened, but as far as I am aware, aircraft in those days weren’t fitted with them.

DOVER: WHITFIELD (See seperate listing with maps and photos)

NOTES: On the 17th April 1913 Gustave Hamel took-off from Dover carrying a British journalist on a non-stop 320 mile flight to Köln (Cologne), in Germany. (The straight line distance from Dover to Köln is about 260 miles incidentally). Here again I am amazed to discover this after four years since starting research for this Guide. Surely this flight should now be regarded as a most significant aviation achievement?

In 2009 I discovered it certainly shocked the British government who, upon hearing of this immediately and officially imposed a wide variety of restrictions on aerial activities according to one writer. Also, this time quoting C C Turner, “For the first time, without previous arrangement, an aeroplane, carrying a passenger, and representing a total weight of nearly a ton, travelled unchecked by any difficulties over five frontiers and the soil of four foreign nations – in a single flight.” The four foreign nations being France, Belgium, The Netherlands and Germany of course. Mind you, regarding “unchecked by any difficulties” C C Turner does also mention, “In addition to the obvious difficulty of the journey, the pilot had to outfly a storm which he overtook before reaching Holland, during which hailstones drew blood where they hit the aviators face.”

From a private pilots point of view, (assuming the 320 mile report is correct?), I wonder why Hamel decided to fly via Holland? Surely a more direct route via Oostende, Ghent and Bruxelles in Belgium, then onto Maastricht (The Netherlands), and Aachen (Germany) would have made more sense? Hamel had no controlled airspace in those days! And, it’s all pretty flat.

DOVER: Temporary airfield? (See SWINGATE DOWN)

NOTES: In his excellent book ‘Taking Flight’ Richard P Hallion states that on August 13th 1914 five dozen Royal Flying Corps aircraft flew from Dover to Amiens without incident - the first time aircraft had flown to war in another country.

My note: Although not about British flying sites in World War One I would highly recommend reading Winged Victory by V M Yeats as it provides a considerable insight into what RFC pilots endured after their training in the UK, and arriving in France. Although ostensibly a work of ‘fiction’ it is regarded as one of the finest accounts of this aspect of WW1. The Daily Mail called it, “The greatest novel of war in the air” and an anonymous fighter pilot in 1941 apparently called it, “The only book about flying that isn’t flannel”. Those pilots did of course face a very uncertain future, with an average life expectancy given as six weeks. So, broadly comparable to RAF bomber crews in World War Two.

Note: The Seaplane base was in the top right corner of this picture.

DOVER HARBOUR: Military Seaplane Station & Flying Boat Base later civil use

Military user: WW1: RNAS

Pleasure flights: ? There seems to be enough evidence of seaplane ‘joy-ride’ activity shortly after WW1 but who was operating the service. AVRO perhaps?

Location: Marine Parade

Period of operation: Military: 1914 to 1919 Civil: early 1920s only?

ANOTHER DOVER FLYING SITE?

This picture, (courtesy of Mrs Rosewarne), was scanned from the excellent book Cornwall Aviation Company by Ted Chapman published in 1979. It shows the Avro 504K G-EBIZ operated by the Cornwall Aviation Company, participating as a sub-contactor for the Alan Cobham Tour of the UK at Dover on the 24th May 1932. The question being, did they use a pre-existing site such as SWINGATE DOWNS, or another site?

If anybody can kindly offer advice, this will be much appreciated.

NOTES: In June 2010 a business acquaintance told me a story of when going on holiday with his family, aged 11, (therefore over forty years ago), and driving down to the Eastern Docks to catch a ferry, his grandfather pointed outa mundane little building/hangar which he claimed was part of the WW1 RNAS site he’d served at. We did the Google street search, followed it along Marine Parade, and lo and behold it was still there! Albiet with folding doors installed.

DOVER: Temporary Landing Site

Location: Duke of York’s Royal Military School

NOTES: On the centenary of Louis Blériots first crossing of the English Channel, (25th July 1909), four restored and replica examples of the Type XI assembled at Sangatte to celebrate the event and to recreate the flight but landing on the cricket pitch of the Duke of York’s Royal Military School (Royal Naval College) rather than crash landing about half a mile away as Blériot did. Incidentally it appears that the intrepid Monsieur Blériot never did get the hang of landing an aeroplane properly and suffered many a 'landing' by damaging the aircraft.

Various news reports seemed to be both confusing and misleading - but that’s the role of the press and media isn’t it? If they are mostly correct it appears the French pilot Edmond Salis did cross the Channel in a restored replica (?) XI before French ATC forbade further flights.

In the September 2009 issue of Light Aviation John Broad penned an article with rather more accuracy thankfully! Taking advantage of a lull in the wind and weather it seems the first to arrive at the Military School was indeed Edmond Salis flying an exact replica except it was powered by a 3-cylinder Potez engine of about 60hp built in about 1932. The Anzani engine Blériot used created about 25hp. Edmond Salis is the son of Jean Sallis who flew one of his collection of Blériot aircraft for the 60th anniversary in 1969, who in turn was the son of Jean Baptiste Salis who flew over for the 50th anniversary in 1959. But where did they both land I wonder? A second Blériot from the Salis collection arrived a short while after.

A PIETONPOL ARRIVES IN DOVER

It may, (or should be?), of interest that Alan James had already flown in with his Pietenpol Aircamper G-BUCO along with David Beale in his Tipsy Belfair to greet the arrivals…but am I jealous? You bet! The Swedish pilot Mikael Carlson did it make it, flying his original, (but restored of course), Blériot XI arriving on the 26th, a day late due to the inclement wind and weather, landing at 09.00 BST after a 33min flight. Sadly few were around to witness this arrival but in a rather odd and fitting way this turn of events mirrors the original crossing in as much as Blériot himself was the second pilot to make the attempt. As pointed out before, the first was Hubert Latham in an Antionette but he ditched after his engine failed. But, the French, bless them, have erected a monument to Hubert Latham.

After the two replica aircraft landed on the 25th an aerial parade of light aircraft flew past having departed from LYDD at regular intervals. Then an amazing aerial armada of about 300 French, Belgian and British microlights flew overhead from France landing at DAMYN’S HALL in ESSEX before flying on to SYWELL. The microlight event was organised by the BMAA. Later the Battle of Britain Memorial Flight flew their Lancaster past, then the Red Arrows followed by their French counterparts, the Patrouille de France. Quite a day! Incidentally the eventwas attended by Louis Blériot’s now rather elderly grandson, also named Louis.

We'd love to hear from you, so please scroll down to leave a comment!

Leave a comment ...

Copyright (c) UK Airfield Guide