Hainault Farm

HAINAULT FARM: Military aerodrome later civil aerodrome (Aka ROMFORD)

Military users: WW1: RFC (Royal Flying Corps) RAF (Royal Air Force)

RNAS (Royal Naval Air Service)

39 [Home Defence] Sqdn (Royal Aircraft Factory B.E.2 & B.E.12 types)

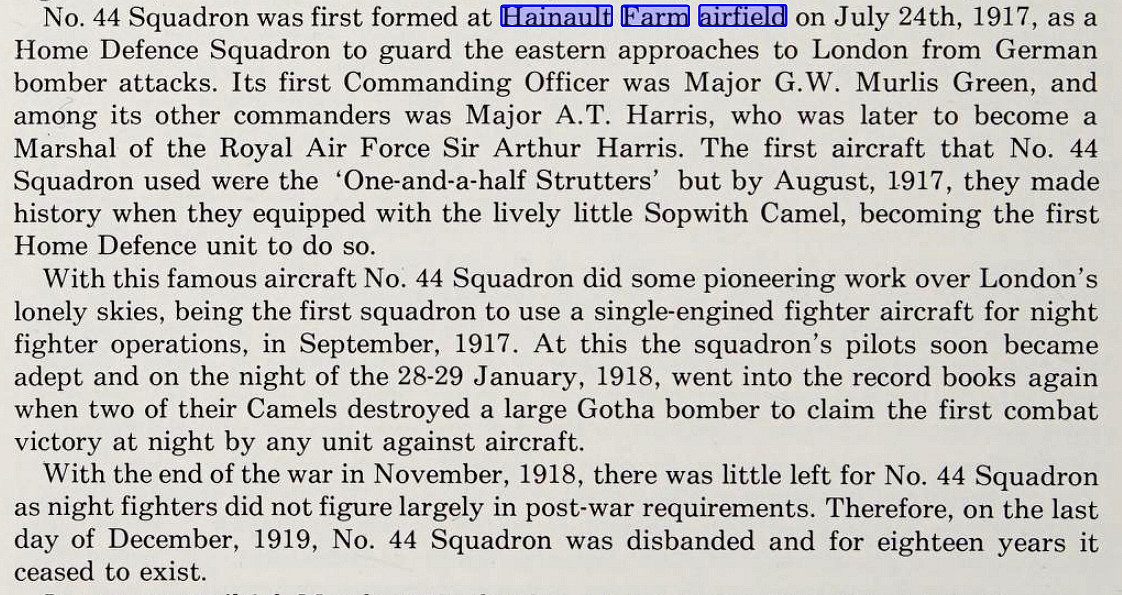

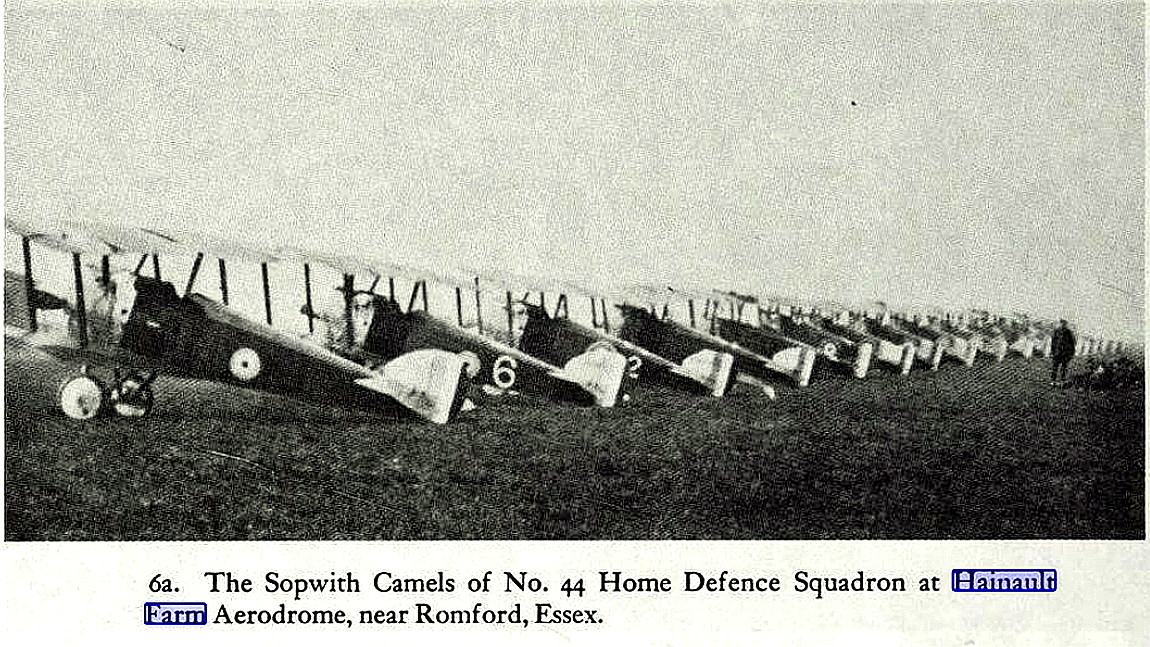

44 & 151 Sqdns (Sopwith Camels)

RNAS Day Landing Ground (1914 to 1915) (Avro 504s)

RFC Home Defence Night Landing Ground (1915 to 1916)

RFC/RAF Home Defence Flight Station (1916 to 1919)

WW2: RAF Emergency Landing Ground for RAF HORNCHURCH

Location: SE of Hainault

Period of operation: Military: 1914 to 1918 Civil: 1920s and 30s? Military again: 1940 to 41

Site area: 100 acres 869 x 686

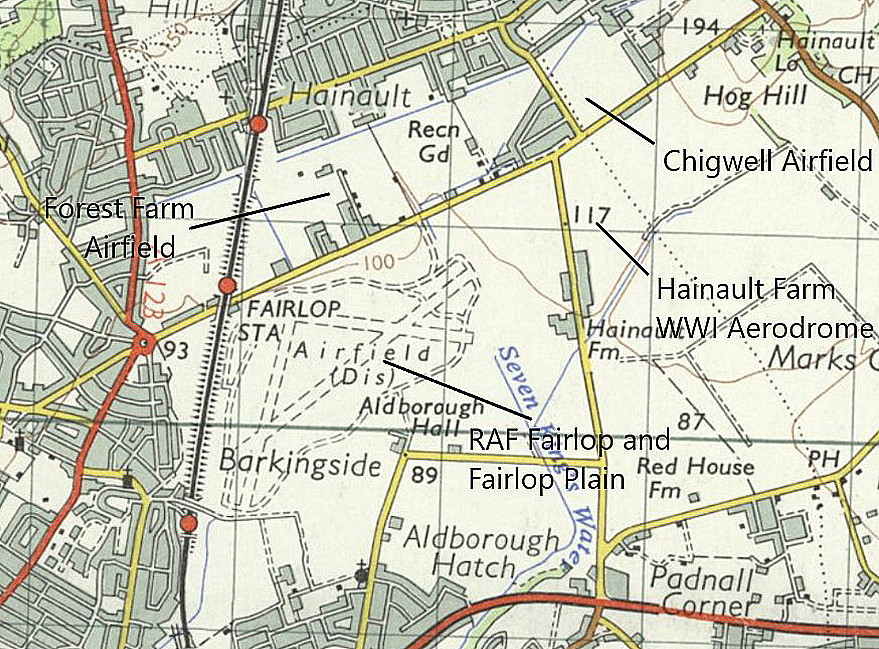

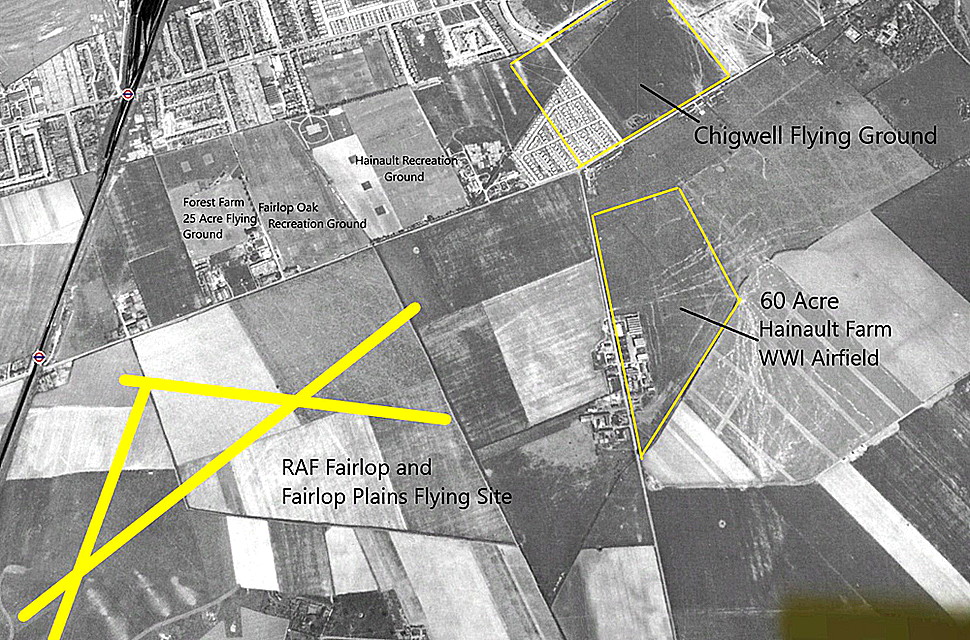

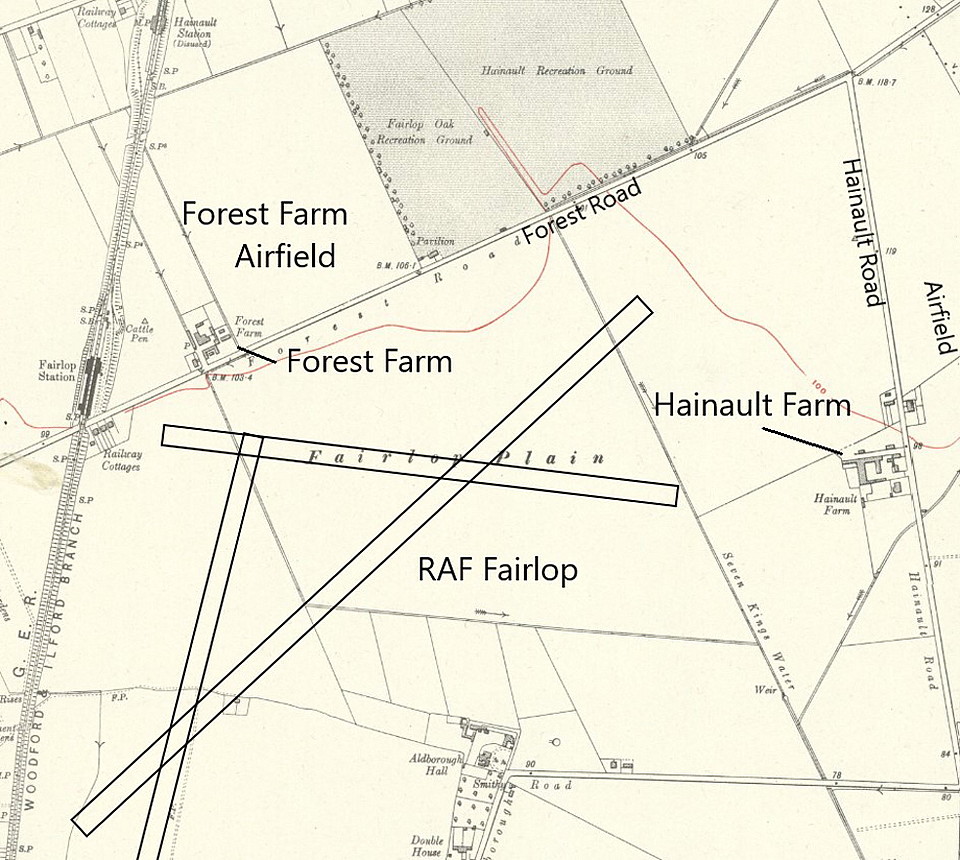

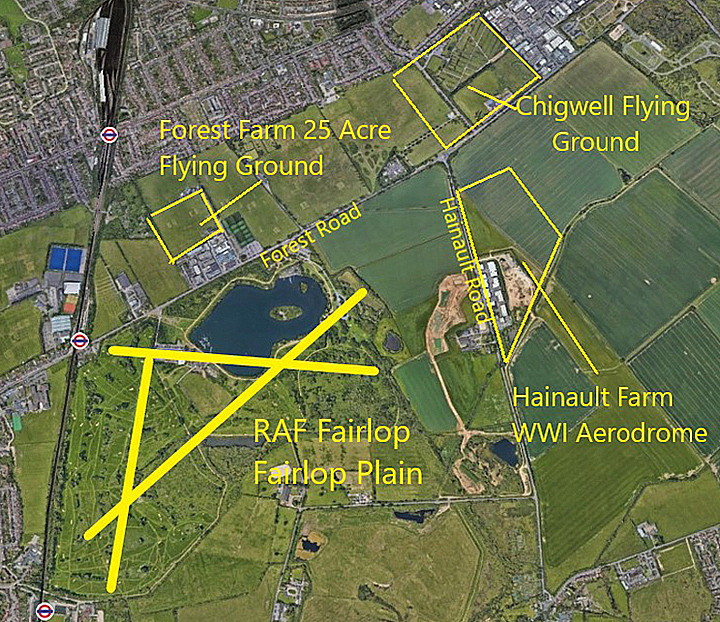

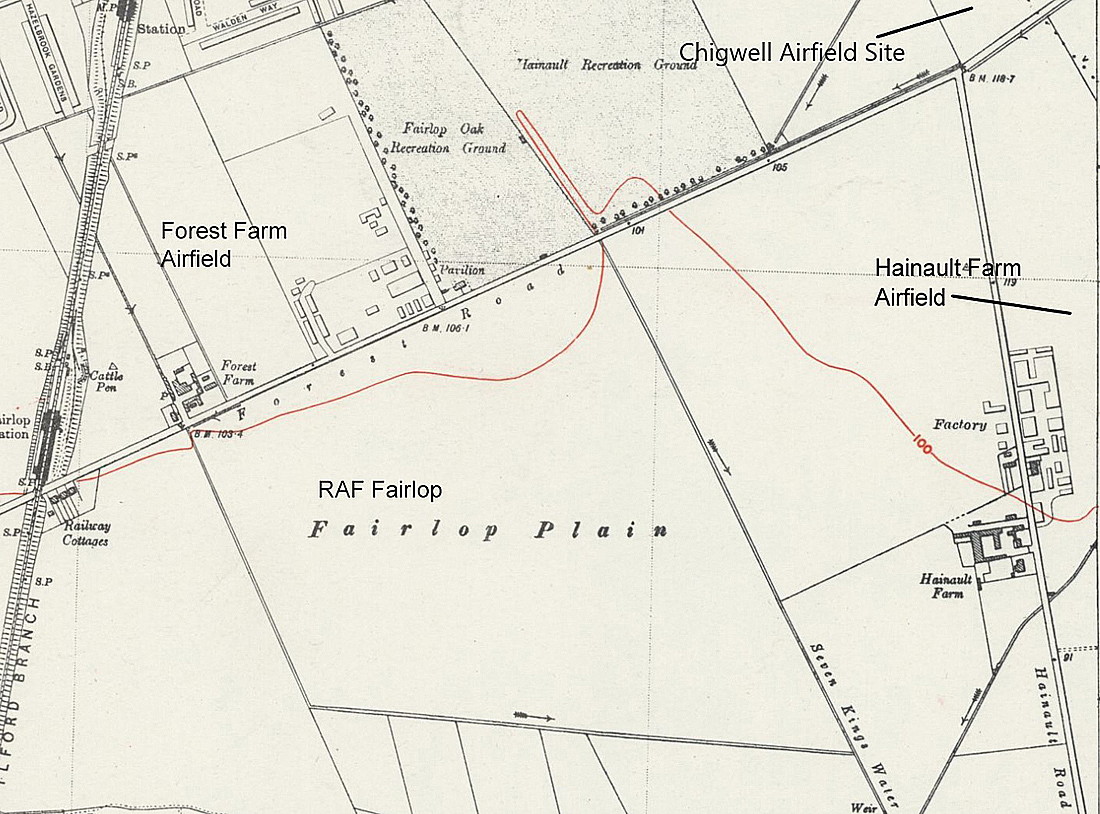

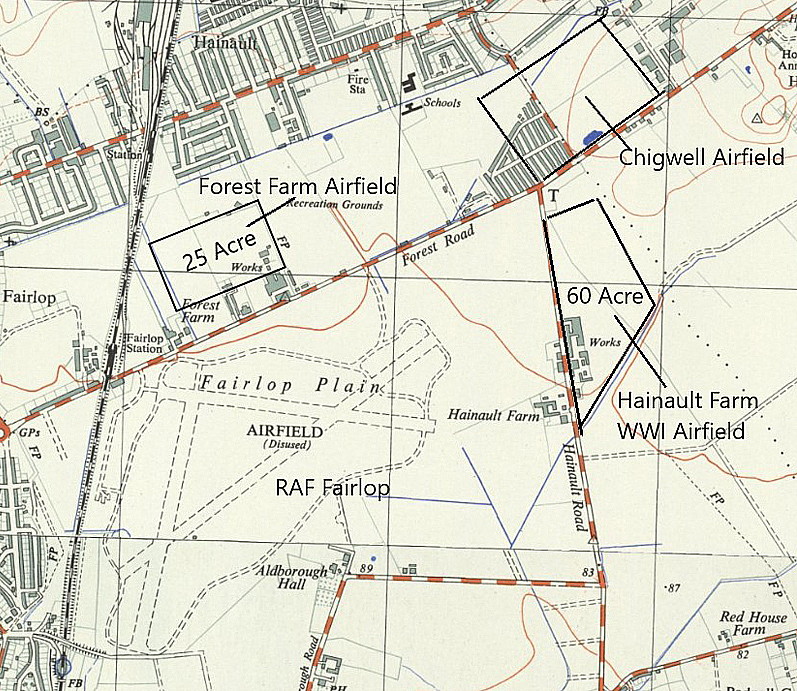

NOTES: In July 2017 I was sent this map by Alan Simpson who has been researching the history. It certainly clears up a variety of issues, and illustrates what must be an unique situation in the UK with four airfields so closely co-located. But it does raise quite a few questions. For example; was 39 (Home Defence) Squadron based both here and 'across the road' at FAIRLOP?

As Alan points out, this map has be overdrawn from a map in John Barfoot's book 'Over Here and Over There'.

A MICHAEL T HOLDER GALLERY

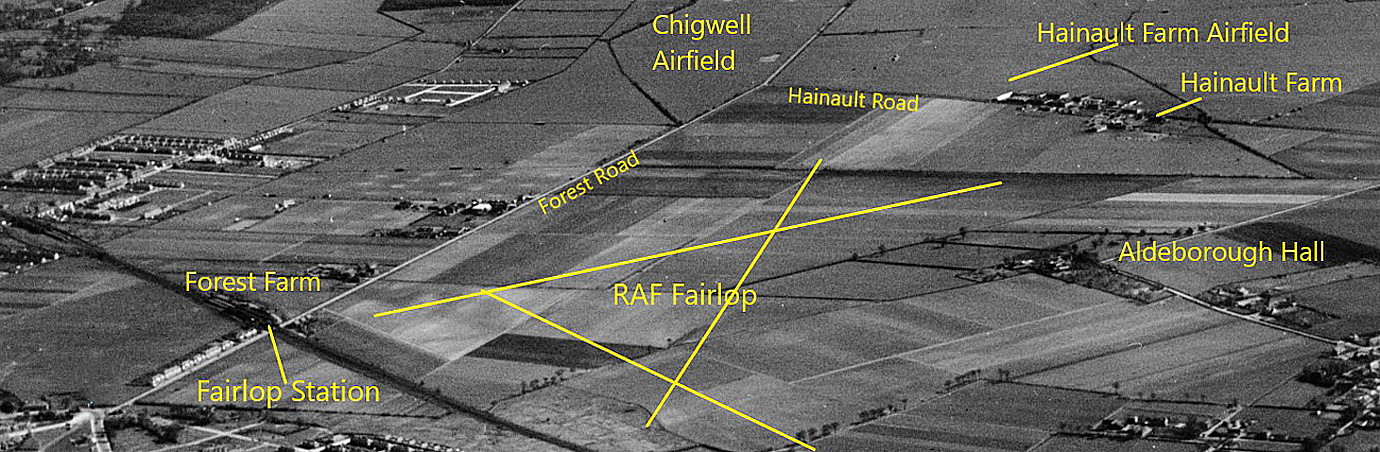

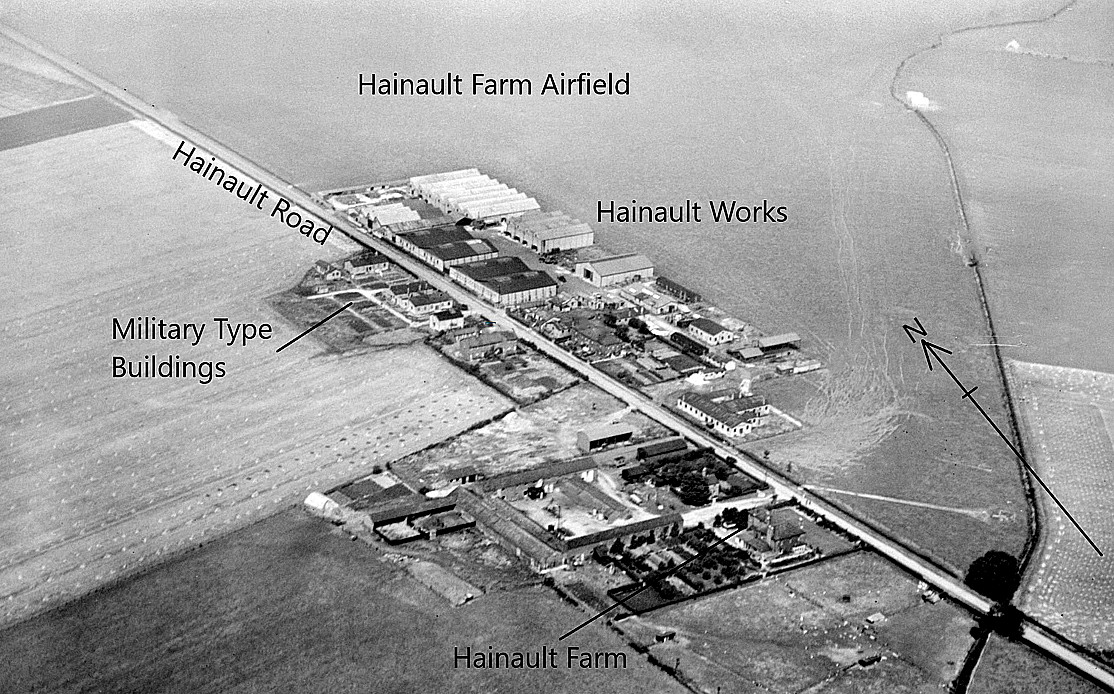

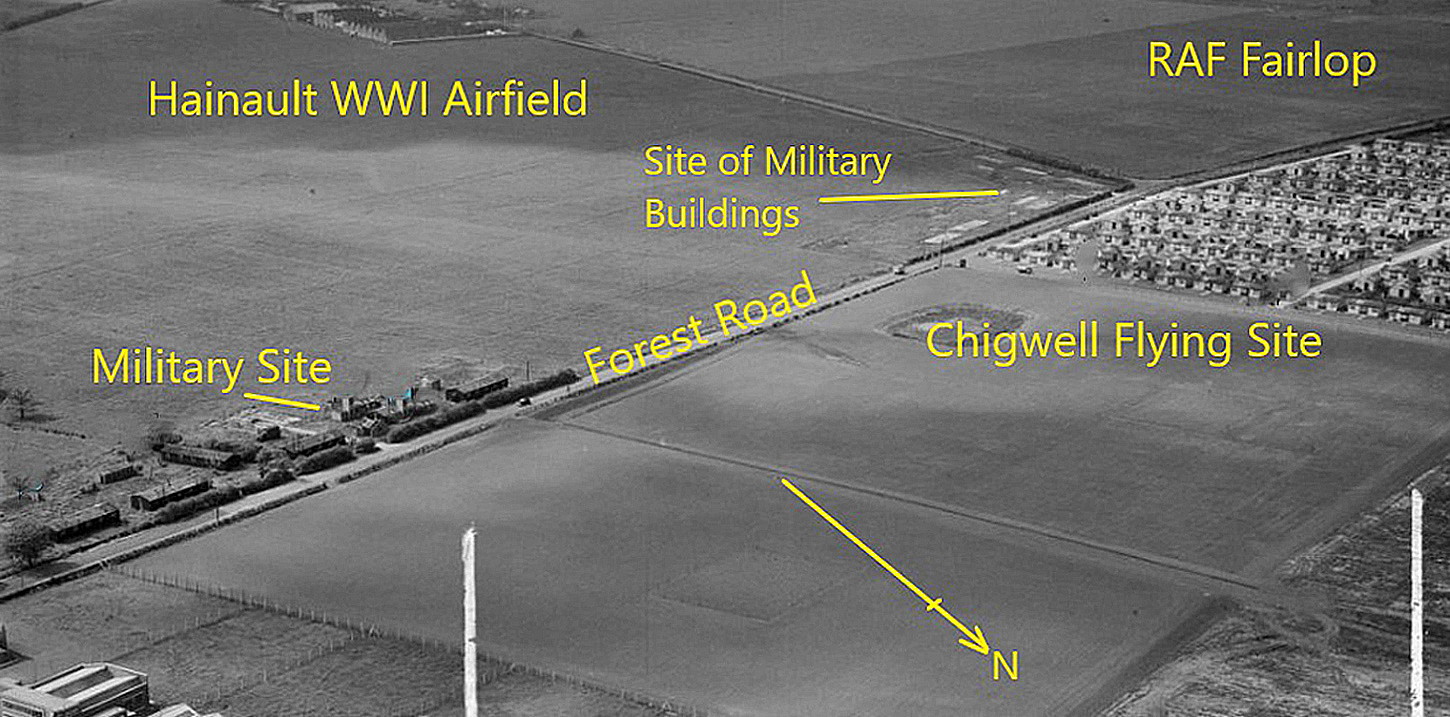

Later, in 2023, Mike Holder, a great friend of this 'Guide', decided to investigate this area containing four airfields (!), to see what else may be available, and these are the results.

The photo of the 44 Squadron pilots was obtained from Essex and its Race for Skies 1900 - 1939 by Graham Smith. Note that FOREST FARM was the western part of WW1 FAIRLOP aerodrome. (See seperate listing)

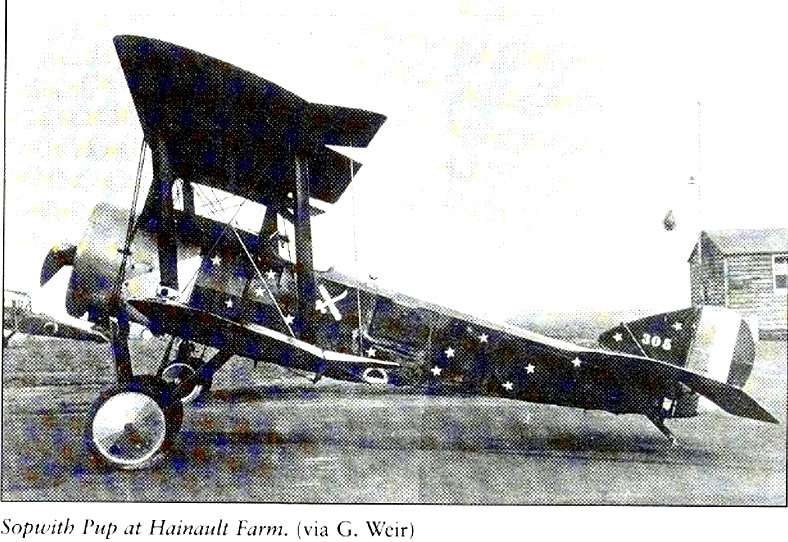

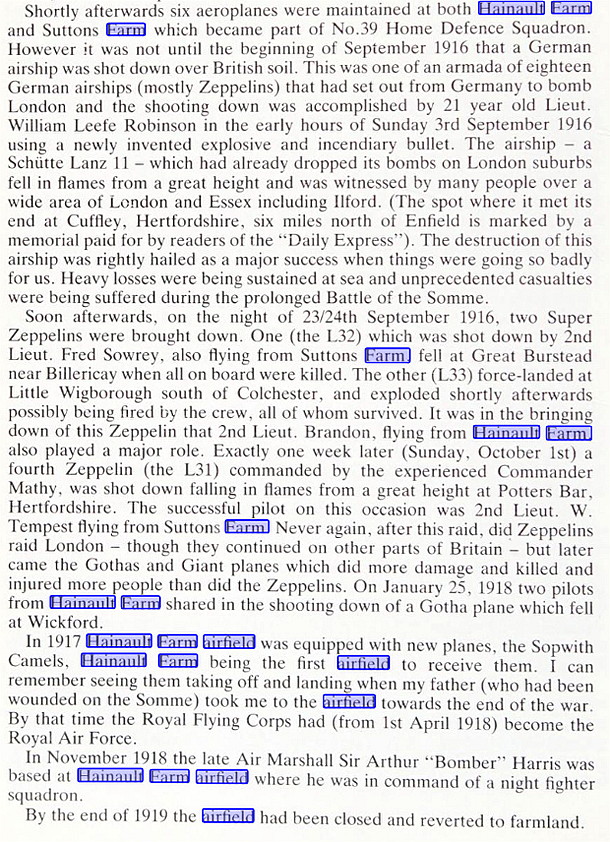

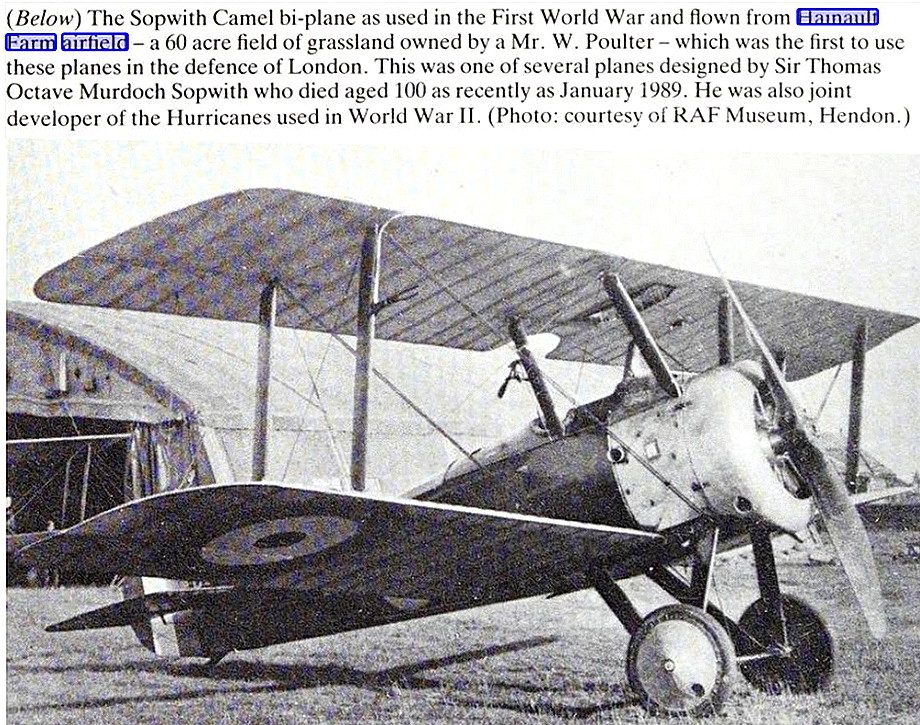

The excerpt is from the Potted History of Ilford by Norman Gunby. The picture of the Sopwith Pup is from Essex and its Race for the Skies 1900-1939 by Graham Smith.

The two excerpts are from The Sky on Fire by Raymond H Fredette.

A CONFESSION TO MAKE

When I started out on this project over twenty five years ago I thought I knew a thing or two about our aviation history - and it turns out I was quite correct. I did indeed know a thing or two - but nothing more! To be quite frank I knew next to nothing, and mostly nothing at all, about any of the flying sites now listed in this 'Guide'. Which of course is precisely why I embarked on the project. There are thankfully so many sources of information now available, especially on the, for me new fangled inter-web, (mostly trustworthy), but have to admit that when starting out I was blissfully unaware of HAINAULT FARM.

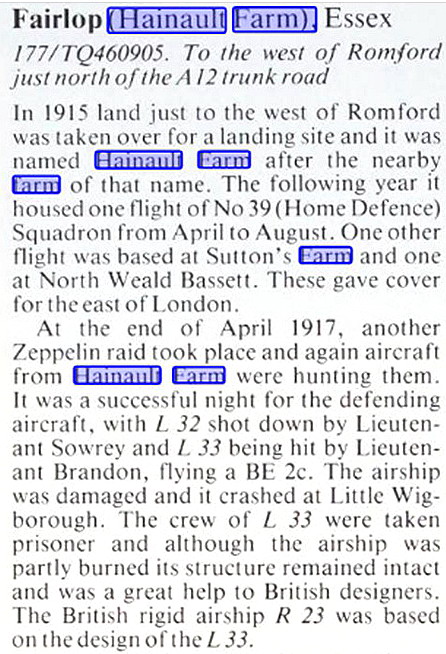

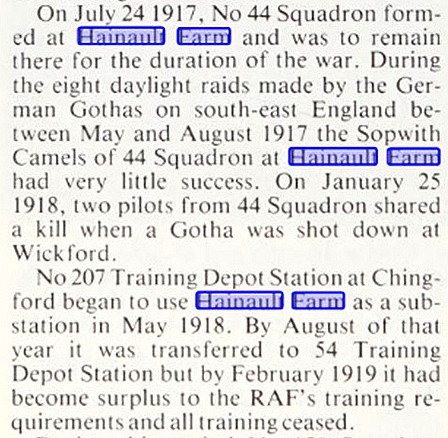

These three excerpts Mike Holder has found are from the fabulous series of books, Action Stations and Action Stations Revisited.

The line-up of Sopwith Camels is from The Sky on Fire by Raymond H Fredette. The excerpt and Sopwith Camel photo are both from the Potted History of Ilford by Norman Gunby.

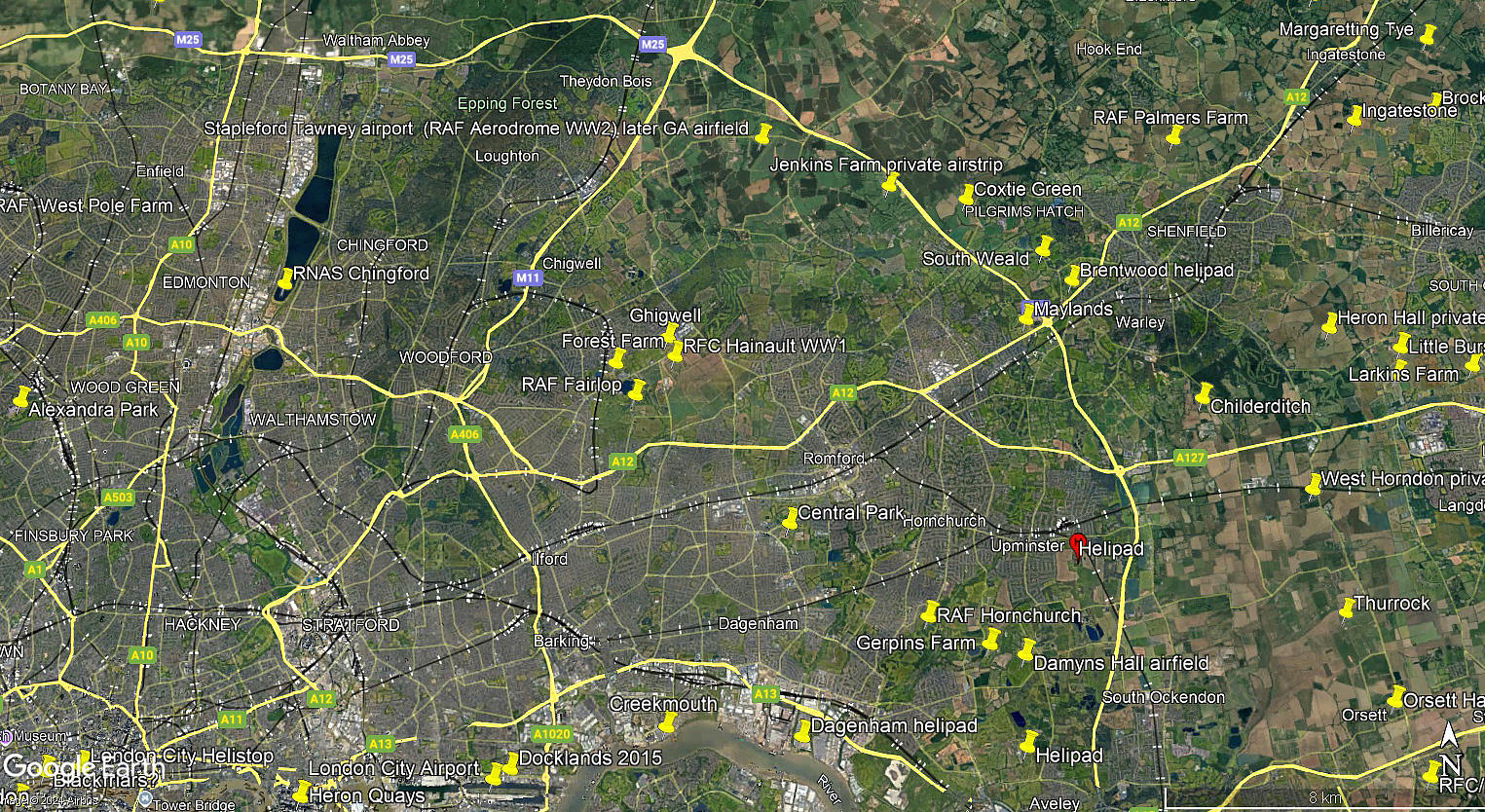

The area view is from my Google Earth © derived database.

A MAJOR VICTORY

In late September 1916 Lt Brandon flying a B.E.2c from HAINAULT FARM attacked the German airship L33 damaging it sufficiently to make it eventually crash land at Little Wigborough, a village I can’t find listed on modern maps. The real significance of this was although partly burned, (the crew survived and were taken prisoner), enough remained to provide British designers with enough information to build, (copy?), their first successful airship design, the R23.

THE BOMBING OF LONDON

When reading most accounts of bombing raids on England by German aircraft in WW1 you can easily be forgiven for thinking only airships were involved. In fact of the 116 attacks recorded, it appears that 53 were by airships and 63 were by aeroplanes! In fact it seems the first bomb to be dropped on England fell upon Dover from a lone aeroplane on Christmas Eve 1914.

This said the “Zeppelins”, (not all the German airships were designed and built by Zeppelin), started raiding in early 1915 and it wasn’t until the ‘Gotha’ entered service, (purpose built to bomb England), in early 1917 that by May German aeroplanes appeared in our skies. Initially these were daylight raids but the reasonably effective deterrent of the Home Defence squadrons led the Germans to make mainly night raids after August 1917.

Initially from May 1917 the RFC squadrons had little success but on the 7th July twenty one Gothas attacked London. About one hundred defending fighters were launched against them and five Gothas were shot down bringing about the end to daylight bombing by the Germans. I find it interesting to consider just how quickly the Germans adapted to night flying - presumably they’d been practising for some time beforehand? By the same token who in their right mind would want to go flying at night today in a Sopwith Camel, Pup or SE.5a? How on earth did they cope? (See below)

The last recorded bombing raid by German aeroplanes, (including both Gothas and the later bigger Giants, some forty in all), was on the 19th May 1918. It seems that six were shot down. It therefore now seems easy enough to understand why the airships now appear to have been the major threat as they not only started well before the aeroplanes, but continued after, and could in the early days out-climb fixed-wing aircraft at altitude. There is another important factor to consider; although they performed more raids the aeroplanes only attacked the south east of England whereas the airships ranged much further attacking East Anglia, the Midlands and the north of England.

THE FIRST NIGHT FLIGHTS

In his now classic autobiography, Sagittarius Rising, Cecil Lewis gives us this account: "When the August harvest moon loomed up over the flats of Essex one evening about ten o'clock, just adter dark, a raid warning came through. Nobody expected it. Most of the pilots were in town. We were thoroughly unprepared. At that time scout aeroplanes were considered tricky enough to land in the day-time, nobody thought of flying them at night. Moreover, most of the pilots had no experience of night flying. None of the machines was fitted with instrument lights, so to go up in the dark meant flying the machine by feel, ignorant of speed, engine revs, and of the vital question of oil pressure. If this gave out, a thing which happened quite frequently, a rotary engine would seize up in a few minutes, and the pilot might be forced down anywhere."

"However, two intrepid spirits crashed off into the warm moonlight, trusting their luck. These were the first night flights made by scout aircraft during the war. They remained up for two hours, failed to locate the raiders, who dropped their eggs and returned home unscathed. The next morning a feverish activity pervaded the squadron. Tenders rushed off to Aircraft Depots and returned with instrument-lighting installations which were hurriedly fitted in the machines. All pilots were instructed to make practice night landings, and in twenty-four hours the Home Defence squadrons ceased to be looked upon as anything but night fighters."

It now seems utterly incredible, and I trust you agree, that such a turn-around could be effected so quickly - and, that with so little experience, squadrons were, nevertheless, considered operational! I'll add just a bit more from Cecil Lewis.

"In those days night landings were effected by illuminating the aerodrome with flares. These consisted simply of two-gallon petrol tins with the tops cut off, half filled with cotton waste and soaked with parafin. They were placed in an "L," the long arm pointing into the wind and the short arm marking the limit past which the machine should not run after landing. The long arm had four flares, and the pilot endeavoured to judge his landing so that his wheels touched down at the first flare, thus bringing him to rest about the third, when he could turn and taxi into the sheds."

And I might add, certain 'airfields' used for night flying later on in WW1 were little more than about three hundred metres square. Without any doubt most operational pilots with some experience were very proficient indeed, but, a 'whizzo prang' was hardly a matter for investigation - just par for the course. If you have not read Sagittarius Rising, please do so - I put it off for far too long. I only wish I had known about it in my teens.

THE FEAR FACTOR

Without any doubt, viewed today, the fear of the 'Zeppelins' is reported to have "struck widespread terror" into the civilian population. And for good reason as the civilian population had never before known such a thing. Compared to the 'Blitz' a quarter of a century later the damage caused can perhaps be considered trifling - but many people died and quite a lot of damage was done. In many ways, this aerial bombardment can be considered as the first appearance of a 'terror' weapon. And of course, the whole point is that nobody knows if they will be the next target.

In his book Britain’s Greatest Aircraft Robert Jackson gives this account: “The first German bombing raid of 1918 was mounted on the night of 28/29 January, when thirteen Gothas and two Giants were despatched to attack London. In the event seven Gothas and one Giant succeeded in doing so, killing sixty-seven civilians, injuring another 166, and causing damage of nearly £190,000. The raid was thwarted to some degree by fog, as far as the Gothas were concerned, while one of the Giants had engine trouble and was forced to turn back, having jettisoned its bombs into the sea off Ostende.”

Attacks by the German military such as this, on a civilian population, are largely forgotten about today. Historically they do of course reinforce the idea that the bombing of German cities during WW2 was much more than simply justified. The unfortunate undeserving German civilian population suffered the brunt of retaliation and in this respect every single bomb dropped on them was more than justified– including Hamburg and Dresden. As the wise saying goes: “You shall reap what you sow.” It might seem difficult to believe today that despite these blatant atrocities by the German military in WW1, the RAF at the beginning of WW2 still had a deep aversion towards bombing civilians.

A SUCCESSFUL ATTACK

Again from Robert Jackson: “One of the Gothas involved in the London attack dropped its bombs on Hampstead at 9.45 pm and was then tracked by searchlights as it flew over north-east London. The beams attracted the attention of two patrolling Sopwith Camel pilots of No.44 Squadron from Hainault – Captain George Hackwill and Lieutenant Charles Banks – who at once gave chase and independently picked up the glow from the Gotha’s exhausts as it passed over Romford at 10,000 feet.

Banks was flying a Camel with an unconventional armament; in addition to its normal pair of Vickers guns it also carried a Lewis, mounted on the upper wing centre section and using the new RTS ammunition. Designed by Richard Threlfall and Son, this combined explosive and incendiary qualities. It was Banks who attacked first, closing from the left to about thirty yards behind the Gotha and opening fire with all three guns. Hackwill meanwhile closed in from the right and also opened fire, effectively boxing in the German bomber and presenting an impossible situation to its gunner, whose field of fire was restricted.

After ten minutes or so the Gotha caught fire and dived into the ground near Wickford, where it exploded. It would almost certainly have crashed anyway, even if it had not caught fire, for a subsequent examination of the crew’s bodies revealed that the pilot had been shot through the neck. Hackwill and Banks were each awarded the Military Cross for their exploit.”

“An hour after the last Gotha had cleared the coast, the Riesenflugzeug was over Sudbury, having made landfall over Hollesley Bay, east of Ipswich, and was droning towards London via a somewhat tortuous route. By this time, at least forty-four fighters were searching for it. Shortly after it had released its bombs over London, the Giant was picked up east of Woolwich by a Sopwith Camel of No.44 Squadron flown by Lieutenant Bob Hall, a South African. Hall followed it as far as Foulness, cursing in helpless frustration all the way because he could not get his guns to work. The Giant got away.

The anti-aircraft barrage scored one success that night, but unfortunately its victim was a Camel of No.78 Squadron flown by Lieutenant Idris Davies, whose engine stopped by a near shell burst at 11,000 feet over Woolwich. Davies tried to glide back to Sutton’s Farm, but he hit telegraph wires near the Hornchurch signal box and was catapulted out of the cockpit. He fell between the railway lines, amazingly without injury, but the Camel was a complete loss. Forty minutes later Davies was sitting in another Camel, ready to take off if need be.”

SOMETHING TO BE LEARNT

There are two lessons here: Firstly that until air-to-air radar became available in WW2, nearly all night interceptions were almost a complete a waste of time and resources in a military sense. However, the huge propaganda machine which was rolled out in the very few cases when a night attack on an enemy aircraft/airship was successful seemed to have had a calming effect on the general population? I have not found one report of even local panic during these ‘terror’ bombing raids.

ANTI-AIRCRAFT GUNS

The second aspect is the dubious value of anti-aircraft guns. It was a virtually worthless deterrent until radar-guided methods were evolved. Indeed, it does appear that in the UK during WW2 our pre-radar anti-aircraft, and so-called defence systems, shot down many more RAF and Royal Navy aircraft than enemy aircraft. Indeed, it now appears the first ‘casualty’ in WW2 was a RAF fighter aircraft shot down by one of our own anti-aircraft batteries. What now seems quite astonishing is that the senior officers in all the military forces must have quickly realised that this strategy was proving to be seriously counter-productive, plus being very costly, wasteful of resources etc, etc. And yet they continued to promote the strategy. Why?

There is another quite important aspect too, and that is that the laws of gravity dictate that what goes up needs to come back down. I have yet to discover a report on how much damage was caused by all this substantial amount of ordnance returning to earth in WW1. I could of course be mistaken, but I believe that it wasn't until WW2 that devices were available to make anti-aircraft shells explode at altitude.

A SUMMARY

It is remarkable, most unusual and possibly unique (?), to find six flying sites co-located in such a relatively small area. Initially Handley Page were using a site north of Forest Road prior to WW1 and this location was absorbed in WW1 for the military FAIRLOP aerodrome. After WW1 we have the short-lived FOREST FARM civil aerodrome at the western end near to Fairlop 'London Underground' station. In the 1930s we have the CHIGWELL aerodrome/airport being established to the east of the WW1 aerodrome.

HAINAULT FARM is located south of Forest Road and south of the later CHIGWELL location. Then in WW2, just west of HAINAULT FARM, we have the much larger RAF FAIRLOP aerodrome. It may not come as a surprise if I admit to being quite confused about these locations when I started this project over twenty-five years ago, but thanks to others offering their generous help, now reckon the situation mostly resolved.

We'd love to hear from you, so please scroll down to leave a comment!

Leave a comment ...

Copyright (c) UK Airfield Guide