Hornchurch

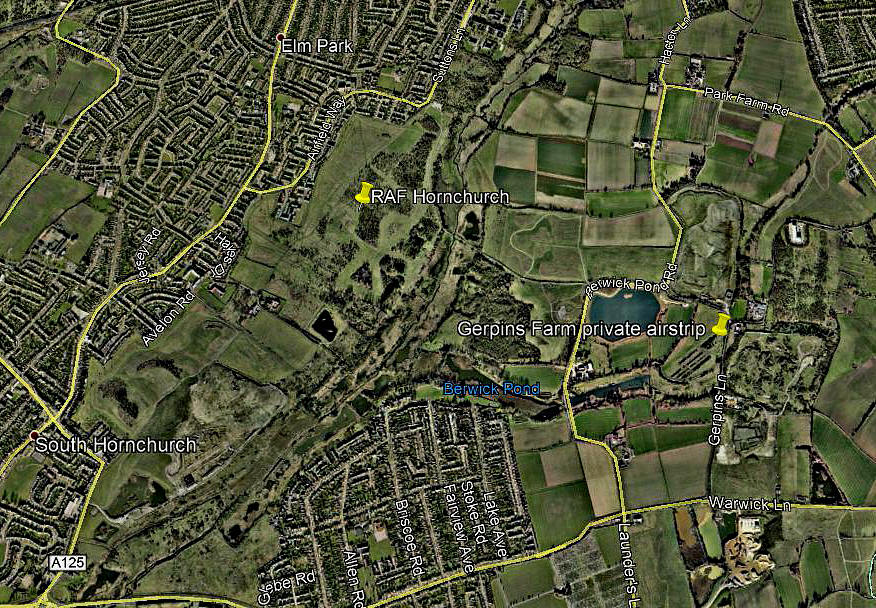

Note: I believe this is the correct location for RAF HORNCHURCH. Could anybody be kind enough to confirm this?

SUTTON’S FARM: HORNCHURCH (See another listing, pretty much the same; see SUTTONS FARM)

Note: This picture of the HORNCHURCH airfield location was obtained from Google Earth ©

Military aerodrome (Later known as RAF HORNCHURCH)

Military users: WW1: RFC/RAF (Royal Flying Corps / Royal Air Force)

Home Defence Flight Station and Night Training Squadron Station

39 [Home Defence] Sqdn (Royal Aircraft Factory B.E.2c and B.E.2e)

78 [Home Defence] Sqdn (Sopwith Camels)

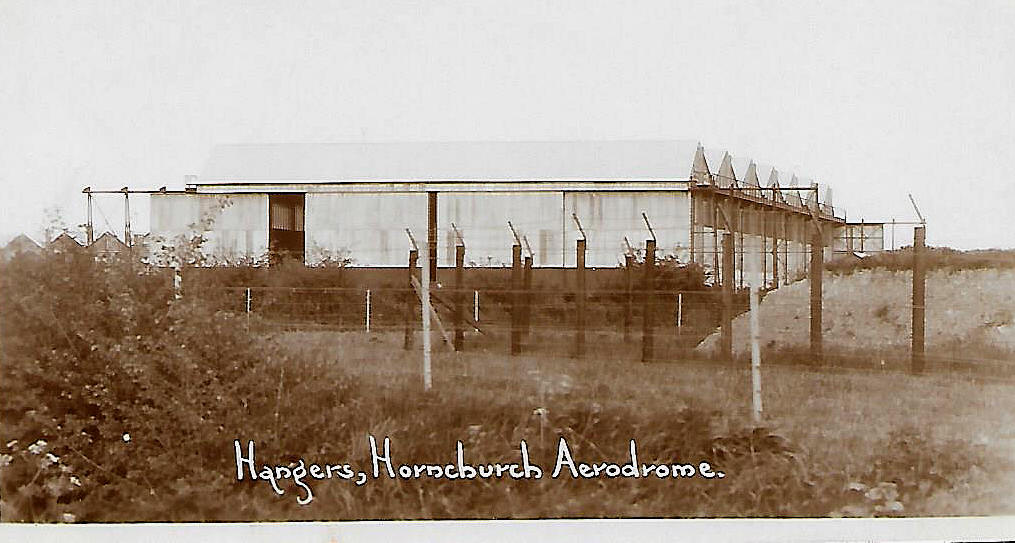

Note: This picture, from a postcard, was very kindly sent to me by Mike Charlton who has an amazing collection of British aviation postcards. See - www.aviationpostcard.co.uk

I would think that this picture was taken in the late 1930s? If anybody can kindly offer advice, this will be most welcome.

1928 to 1939: RAF Fighter Command

54 Sqdn (By 1938/9 Gloster Gladiators then Vickers-Supermarine Spitfires)

65 Sqdn (Hawker Demons, Gloster Gladiators)

74 “Tiger” Sqdn (Hawker Demons)

111 Sqdn (Armstrong Whitworth Siskins, Gloster Grebes, Bristol Bulldogs)

WW2: RAF Fighter Command 11 Group

*BATTLE OF BRITAIN SQUADRONS

54 Sqdn (Vickers-Supermarine Spitfires)

74 Sqdn (Vickers-Supermarine Spitfires)

266 Sqdn (Vickers-Supermarine Spitfires)

LATER IN WW2

41, 54, 64, 65, 74, 92, 222 (Natal), 340 (Free French), 485 (RNZAF), 603 (City of Edinburgh) and 611 Squadrons: (All flying Vickers-Supermarine Spitfires)

‘Comms Flight’ (Westland Lysanders &?)

70 Group

567 AAC Sqdn (Hurricanes, Martinets & Vengeance TT)

Location: Just NW of Hornchurch Country Park, W of the A125, in the area now known as Elm Park, about 2nm SE of Romford

Period of operation: 1915 to 1919 Then 1928 to 1962

Site area: WW1: 105 acres 731 x 686

Runways: WW2: N/S 1463 grass NE/SW 1463 grass

E/W 1463 grass

NOTES: Apparently the first “Zeppelin” to be shot down over England was by a BE2c fighter of 39 Squadron from SUTTONS FARM on the night of 2nd/3rd September 1916 - the pilot was Lt Leefe Robinson. It would appear that this airship which crashed at Cuffley in Herts wasn’t a Zeppelin type at all, but a Schutte-Lanz type, (the clue is in the serial number S.L. 11?). “Zeppelin” became the generic term for all German airships and many writers on aviation history fail to make this distinction, including me until 2005!

However, it appears this Squadron did shoot down an actual Zeppelin, (the L32 commanded by Werner Peterson), not long afterwards on the night of the 23rd/24th September. The pilot this time was Second Lieutenant Frederick Sowrey flying the BE2c, serial 4112 which is still preserved, (still at DUXFORD?), and Sowrey was awarded the DSO. In keeping with my new found love of aviation history in some depth, this BE2c made an earlier but unsuccessful attack on the Zeppelin LZ97 on the night of the 25th/26th April, flown by Captain Arthur T Harris. He who went on to lead Bomber Command in WW2 and known to the public as “Bomber” Harris, but “Butcher” Harris to his aircrews.

SOME NUMBERS

2nd March 2015. The following is something I wrote over ten years ago.

In doing this research I have had to keep continuously revising my perceptions about UK aviation history. In fact when I say revising - the truth has been; dump the lot and start from scratch! Just one example; to me NORTH WEALD is a major London aerodrome, steeped in history. Today, (and for some time actually), seemingly forever under threat from people who couldn’t care less about our aviation heritage or anything else except making piles of money by redeveloping the site. When starting this research I hadn’t even heard of RAF HORNCHURCH, (previously the WW1 RFC aerodrome known as SUTTON'S FARM), but I’ve discovered an interesting statistic which to me at least shows how

very quickly our perceptions about the importance of an aerodrome to the ‘local’ population so quickly changes even over a few years. In 1939 it appears that two major military air displays were held in this area, one at NORTH WEALD and the other at HORNCHURCH. It is reported that over 15,000 people attended the display at NORTH WEALD but 45,000 turned up to see the display at HORNCHURCH!

THE WW2 ERA

This was a time when individual pilots often achieved at least minor celebrity status. With HORNCHURCH squadrons becoming equipped with Spitfires their role of honour became assured during the ‘Battle of Britain’. For No.74 (Tiger) Squadron for example, pilots like “Sailor” Malan, “Tink” Measures and “Paddy” Treacy arrived. 65 Squadron could boast Stanford Tuck, Brian Kingcombe, Oliver and Proudman - obviously a Squadron with pilots not imaginative enough to invent nick-names? No.54 Squadron had “Al” Deere, Leathart and “Toby” Pearson. Obviously in later years a rich picking ground for writers of comic sketches for radio and TV. Being just a tad serious though, we really must remember just how much these pilots with their now seemingly comic nicknames contributed so much to the war effort.

The tradition in the RAF of assigning nicknames still continues.

SPITFIRE SQUADRONS

At HORNCHURCH in early WW2 No.54, 65 and 74 Squadrons were all flying Sptifires. It must be explained and emphasised time and time again that during WW2 especially and at other periods RAF Squadrons were in the main, and still are, always on the move! With a Guide such as this, only a ‘snapshot’ is possible to indicate the general nature of flying activity. For example, when the ‘Battle of Britain’ reached it’s all-out phase, when the balance of air power really did reach a critical point, DEBDEN onlyhad 17 Sqdn based there, NORTH WEALD had 151 Sqdn but HORNCHURCH had three Spitfire squadrons based here.

After the ‘Battle of Britain’ (which was nothing of the kind of course and mostly only seriously affected the south eastern portion of the country in terms of RAF involvement), it wasn’t long before the UK took an offensive attitude. To quote Robert Jackson from his book Britain’s Greatest Aircraft: “By March 1941, fighter sweeps over the continent were becoming organised affairs, with the Spitfire and Hurricane squadrons operating at wing strength. A Fighter Command wing consisted of three squadrons, each of twelve aircraft. There were Spitfire wings at Biggin Hill, Hornchurch and Tangmere, mixed Spitfire and Hurricane wings at Duxford, Middle Wallop and Wittering, and Hurricane wings at Kenley, Northolt and North Weald.”

It was when flying from here, at the head of a HORNCHURCH wing in the ‘Battle of Britain’, and knowing he couldn’t possibly survive the attack on his crippled aircraft “Paddy” Finucane broadcast his so few but now famous last words, “This is it, chaps”.

THE BATTLE OF BARKING CREEK

In his most excellent autobiography A Willingness To Die Brian Kingcome describes one incident in the ‘Phoney War’ period which the authorities dearly hoped would remain deeply buried. In RAF circles it became known as ‘The Battle of Barking Creek’. Basically an authorised air test of a Hurricane triggered off an all-out offensive, against ourselves! One Hurricane pilot died, shot down by a Spitfire, another Hurricane pilot baled out, and the ack-ack crews tried to shoot down everybody and fortunately missed. It really was a utter fiasco. Please read this book. Without any doubt it was, for me, quite a revelation.

WAS HORNCHURCH BOMBED?

Oddly perhaps I haven’t come across an account of the Luftwaffe bombing HORNCHURCH although surely they must have done? In his excellent book Wings Patrick Bishop describes how the 15th September 1940 became a very significant date: “This was subsequently taken as the point when the battle turned in Britain’s favour – though it did not feel like that to the pilots. The Luftwaffe had spent August following the sensible course of battering Fighter Command on the ground. Six of the seven sector stations in 11 Group had been bombed almost to the point of collapse and five of the advanced airfields were severely damaged. In the air, just over 300 RAF pilots had been lost and only 260 had arrived to replace them, and the factories were struggling to keep replacement aircraft flowing to the squadrons. This did not mean that Fighter Command was on the point of collapse. The system was strong and even if the 11 Group stations had been knocked out there were other lines of defence to fall back on in the West and Midlands.”

It seems to me that the biggest mistake made during the ‘Battle of Britain’ was to keep any aircraft based in KENT. A hurried withdrawal of aircraft and facilities to stations just beyond the circle of range of Me 109s would surely have produced much better results? Which in effect was what happened to some extent when the Luftwaffe switched to bombing London and the Luftwaffe really got a pasting with losses so severe they switched to night-time bombing which the RAF was almost powerless to counter. But of course, isn’t hindsight such a wonderful commodity. Another aspect is that the wholly inaccurate and somewhat emotive term “Battle of Britain” is grossly misleading. Indeed, although not much better, the “Battle of Kent and Sussex” would be better suited. Most of the United Kingdom and the majority of RAF Stations took little if any part in the proceedings. Please remember this for example, the majority of Bomber Command Stations were virtually untouched.

Returning to Mr Bishop’s account: “As it was, miraculously, the pressure lifted. On 7 September the Luftwaffe changed direction. The 11 Group bases were left alone. The target now was London. The decision was based on Goering’s natural impatience and the belief (stubbornly maintained, despite the evidence that the RAF was still well-stocked with aircraft) that Fighter Command was on its last legs. That hot, sunny Saturday the Blitz began. Just before 4-45 that afternoon the sirens sounded and soon great fleets of bombers were laying waste the East End. Twenty-three squadrons raced to catch them and an epic dogfight involving more than 1,000 aircraft developed over the city.” The RAF did not perform well: “Only thirty-eight enemy aircraft were shot down, while RAF losses totalled twenty-eight, with nineteen pilots killed.”

Some quick thinking was required and when the next major raid on London came, on the 15th September, the results were very different. As Mr Bishop states: “By the end of the day the same satisfaction was being felt all across Fighter Command. Wreckage of German aircraft and burned bodies lay in fields, lanes and streets all over south-east England. The figure of destroyed aircraft was given: 183 – a considerable exaggeration, as the true figure was nearer 60. RAF losses were light: 25 aircraft lost and 13 pilots killed.”

The result, put very simply, was the Blitz on British cities and here the experts had got it completely wrong. Catastrophic bombing did not produce widespread panic and chaos; if anything quite the opposite. It seems astonishing how large communities react. Faced with the ‘threat’ of so-called Zeppelin attacks in WW1, and indeed a few bombs being dropped, the British public reacted out of all proportion to the actual danger. But, when faced with a truly massive onslaught with appalling loss of life and damage to property, the majority dug their heals in and kept on going. England did not see the roads clogged with refugees desperate to escape. But of course, they didn’t have columns of troops and tanks advancing on them either.

For some reason, (it was the same in Germany later of course), the civilian population found something within themselves capable of resisting the most appalling bombing raids. Plus of course it provided, in London certainly, the surprisingly large ‘criminal class’ with a bonanza beyond their wildest dreams. I suspect this happens in every society everywhere faced with similar circumstances. The riots in London recently being added proof. Opportunism is very much an integral aspect of survival for many people – including many bankers, lawyers and especially politicians. It isn’t just a class issue.

Regarding the ‘Battle of Britain’ Mr Bishop states: “The victory lit a beacon of hope. This was the first time since German territorial expansion began in 1938 that Hitler’s forces had suffered a major defeat. Out of this came practical consequences that would profoundly affect the course of the war.”

Michael Holder

This comment was written on: 2020-05-08 15:51:20From the 25k Ordnance Survey published in 1959 - Hornchuch Airfield 51 32 18"N 000 12 32"E - approximate centre of the field. The map still shows 3 hangars on the NW of the field.

Les Tyler

This comment was written on: 2021-04-10 14:41:19As a national serviceman, I remember attending a 3-day aircrew selection board at Hornchurch in 1952 when the wartime buildings were intact.

We'd love to hear from you, so please scroll down to leave a comment!

Leave a comment ...

Copyright (c) UK Airfield Guide