Linton-on-Ouse

LINTON-on-OUSE: Military aerodrome

Note: All four of these pictures were obtained from Google Earth ©

Military users: WW2: RAF Bomber Command 4 Group

35 Sqdn (Handley Page Halifaxs)

58 Sqdn (Armstrong Whitworth Whitleys)

76 Sqdn (Initially Whiteleys, then Halifaxs and later Avro Lancasters)

78 Sqdn (Whitleys later Halifaxs)

6 Group (RCAF)

408 (RCAF) Sqdn (Avro Lancasters and later Handley Page Halifaxs!)

426 (RCAF) Sqdn (Avro Lancasters and later Halifaxs!)

Post 1945: 92 Sqdn (Gloster Meteors)

1953: 275 Sqdn (Bristol HC.13 Sycamore helicopters)

1 FTS (Jet Provosts in 1975 for example)

1 HIFTS

1998 snapshot: RAF Flying Training (Basic)

1 FTS 66 x Tucano T 1 (Facilities shared with the Central Flying School at TOPCLIFFE)

207 (Reserve) Sqdn (Short Tucanos)

2007 to 2011: 76 (Reserve) Sqdn (Short Tucanos)

2013: Yorkshire Universities Air Squadron (Grob 115 Tutors)

2014: 72 (Reserve) Sqdn (Tucanos)

Gliding: 1997: 642 VGS (Gliding listed as operating from 1975)

Location: W of A19, NW of Linton-on-Ouse village, roughly 7.5nm NW of York city centre

Period of operation: 1937 to 2014?

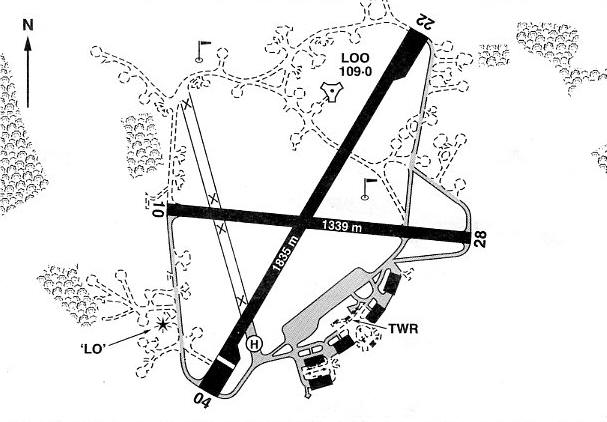

Note: This map is reproduced with the kind permission of Pooleys Flight Equipment Ltd. Copyright Robert Pooley 2014.

Runways: WW2: 04/22 1829x46 hard 10/28 1280x46 hard

17/35 1280x46 hard

2000: 04/22 1835x46 hard 10/28 1339x46 hard (1990s also)

NOTES: In his excellent book Bomber Crew John Sweetman gives considerable insight into the history leading up to WW2 and the earliest stages. As often as not his accounts left me bewildered, not knowing whether to laugh or cry in equal measure. One point mentioned was the leaflet dropping campaign which, (possibly?), 78 Squadron based here might have participated in when flying the Whitley?

An interesting point he makes is that after the ‘Phoney War’ when the RAF had airfields in northern France early in 1940, these enabled Bomber Command much greater range within enemy territory, certainly so for leaflet bombing. Many senior RAF officers were highly sceptical about the effectiveness of this campaign. One, later to be known as ‘Butcher’ Harris by his aircrews, and ‘Bomber’ Harris by the public, maintained the only achievement ‘was to supply the Continent’s requirement of toilet paper’.

THE FIRST HALIFAX SQUADRON

It is claimed that 35 Squadron, based here in 1941, (others say they were based at LEEMING), were the first to use the Halifax on an operational mission on the 10th March 1941. Typically other sources claim this was the raid on Le Havre in France on the night of 11/12 March.

What I now find very interesting is that the Handley Page Halifax first flew on the 25th October 1939 and was introduced into RAF service on the 13th November 1940. This appears to indicate that it took just a year and a half to get production started in sufficient numbers to get aircrews trained up to operational combat status. A phenomenal achievement. However, it must be pointed out that aircrews had to accept that they were flying a type which had hardly been properly tested and in effect had to do much of the 'flight testing' on operations - something it appears that they were quite willing to do - given the circumstances and the opportunity to hit back at the enemy.

76 SQUADRON

I found this in Max Hastings most excellent book Bomber Command, first published in 1979. "76 Squadron, one of 4 Groups Halifax units stationed at Linton-on-Ouse in Yorkshire, lost a steady one and occassionally two aircraft a night throughout the Battle of the Ruhr. In 1943 as a whole, its crews operated on 104 nights and lost 59 aircraft missing, three times their average operating strength. Sometimes weeks went by without a crew successfully completing a tour."

The so-called 'Battle of the Ruhr' is highly misleading. Although the Ruhr region was the main target area, raids ventured as far afield as Berlin, Nuremberg and Munich within Germany. !943 was the turning point for Bomber Command, at last they were equipped with technology that mostly aided navigation, resulting in more accurate bombing. Even so, most bombs did not fall within three miles of the target.

The sad truth is that the bombing campaign by Bomber Command, did not lead to the war ending, as was predicted. Not even after the USAAF joined in. But in theory at least it could have done, especially after Hamburg when four raids in succession obliterated the city. It appears that Bomber Command feared that doing this on other cities would concentrate German defences, with unacceptable losses.

Without any doubt, after the Hamburg raids, the Nazi regime should have surrendered. It was quite clear what Bomber Command on their own could achieve. But delusions reigned supreme, a new generation of terror weapons, the V.1 and V.2 were being developed, and victory was still in sight. Quite why the Nazi's still believed this, after the Americans got involved, remains a mystery.

And, perhaps I should add, when 76 Squadron were ordered to move to the muddy, godforsaken airfield at HOLME-on-SPALDING-MOOR, and live in Nissen Huts, in order to make way for the Canadians in 6 Group, they were very unhappy - and you can easily see why - considering what they had already been through. But that is how Bomber Command worked.

SOMETHING TO BE EXPLAINED

As with many RAF stations especially in WW2, squadrons came and went often on a frequent basis. Considering the size of the task and the upheaval caused it does make one wonder what the principle reason was, or multiple reasons were, behind this policy. As a general rule stations on operations had either one or two squadrons based at any one time, dependent on the airfield size or area and/or the amount of dispersals available. A fully equipped fighter or bomber squadron would normally consist of 36 aircraft divided into three flights – A, B and C Flights and sometimes a Flight would be briefly based elsewhere for a variety of reasons.

Looking up the history of 408 and 426 (RCAF) Squadrons something certainly unusual and just possibly unique happened? Regarding 426 Sqdn, after flying Vickers Wellingtons at DISHFORTH they were moved to ‘LINTON’ to fly Lancasters, (albeit with Bristol Hercules radial engines), and then converted to Halifaxs! Are these the only examples of this happening? One can only imagine the opinions of the RCAF aircrews upon learning that after training up on Lancasters, they were then to fly the Halifax.

STILL VERY CONTROVERSIAL ISSUES

Viewed from the 21st century it is now relatively easy to see that the possibility of the RAF, (and indeed the British government), having Nazi sympathisers within the higher ranks, manipulating the systems to the advantage of the Germans, now appears pretty damned obvious? If true it really does explain so much. Should this come as a surprise? Probably not I would say, as our Royal family was essentially German, so surely it follows that many in their ‘establishment’ would be biased or even ‘pro-German’. Fearing a public backlash they quickly changed their family name to ‘Windsor’. A good call, still working today.

LMF - LACK OF MORAL FIBRE

The LMF issue, ‘Lack of Moral Fibre’, was perhaps just one step down from facing a firing squad for desertion -as practised in WW1. When the chances of surviving a ‘Tour’ of thirty operations was 50/50 at best, is it so small a wonder that many suffered a lack of will to continue. Indeed, the realities of being in a bomber stream would, without any doubt, make any sane person refuse to go again. This conundrum formed the basis of Catch-22 written by Joseph Heller, (Started in 1953, first published in 1961), which became a best-seller novel.

I suppose we do need to recognise that many of those ‘heroes’ who gladly kept going to ‘fight the Hun’ were not exactly entirely in touch with reality? Although many did find it quite easy to accept their death was ‘a price to be payed’ in the interest of a patriotic sense of duty, others struggled to equate this with the concept of something tantamount to deliberate suicide - as ordered. And who can find fault with that logic?

Once again, in his excellent book Bomber Crew John Sweetman gives a fine example of how this was dealt with: “….cases of so-called Lack of Moral Fibre (LMF), refusing to fly or perform duties in the air, were not unusual in Bomber Command. In other ways a sympathetic and compassionate commanding officer, at 76 Squadron Wing Commander Leonard Cheshire ruthlessly rooted out aircrew suspected of this failing.” (My note: But he was of course a zealot and remained so after the war). We most definitely needed zealots, and of course, the Cheshire Homes he founded after WW2 are quite rightly renowned and respected. “He argued that swift action was necessary in the interests of the man himself and, more importantly, of others. ‘That sort of thing could spread like wildfire, like an disease,’ he insisted. ‘I could not afford to hesitate as soon as there was a hint of a problem.’ Yet he is reputed to have taken a decorated man, suspected of LMF, in his own aircraft to give him a chance of redeeming himself.”

A truly wonderful man, trying and often succeeding I think, to balance the utterly brutal bombing regime (afflicting both sides in the war), with compassion and humanity. A clearly almost impossible task for us mere mortals.

2014

To quote from Pilot magazine (June 2014): “ Royal Air Force Tucano solo aerobatic displays will be flown this year by Flight Lieutenant Dave Kirby, who is scheduled to carry out more than sixty displays at forty venues in the UK and overseas. The 2014 display Tucano has received a special livery to commerate 100 years since the outbreak of the First World War. It features a ‘cloud’ of poppies around the nose and the words Lest we Forget, which are also carried on the aircraft’s underside with a single large poppy.” A wonderful tribute.

JUST A NOTE

In June 2014 I once again visited the Menin ‘Gate’ Memorial in Ypres, Belgium. I had once thought this was a memorial to those in the military who had died in WW1, the lists of names inscribed numbering thousands. After a first visit I learnt that all these deaths occurred just in the battle of the ‘Ypres Salient’. In 2014 I noticed an inscription, placed high up, stating that this monument was actually to those for which no remains were discovered after that battle, and therefore they have no grave in the many local war cemetaries to witness their existence.

It is of course quite impossible to distinguish, in that conflict, what sort of death would have been preferable? And for the pilots (and observers) involved after arriving at 'The Front', they rightly knew that most of them would die within a very short time span – measured usually in weeks if not hours. Troops on the ground admired the fliers, it seemed so glamourous to most of them, but being shot down in flames (without a parachute) was the dread of pilots and observers. Many jumped to end it quickly.

There are many very, very good books available on this subject - and I would really recommend reading all of them - a task I am still trying to accomplish.

We'd love to hear from you, so please scroll down to leave a comment!

Leave a comment ...

Copyright (c) UK Airfield Guide