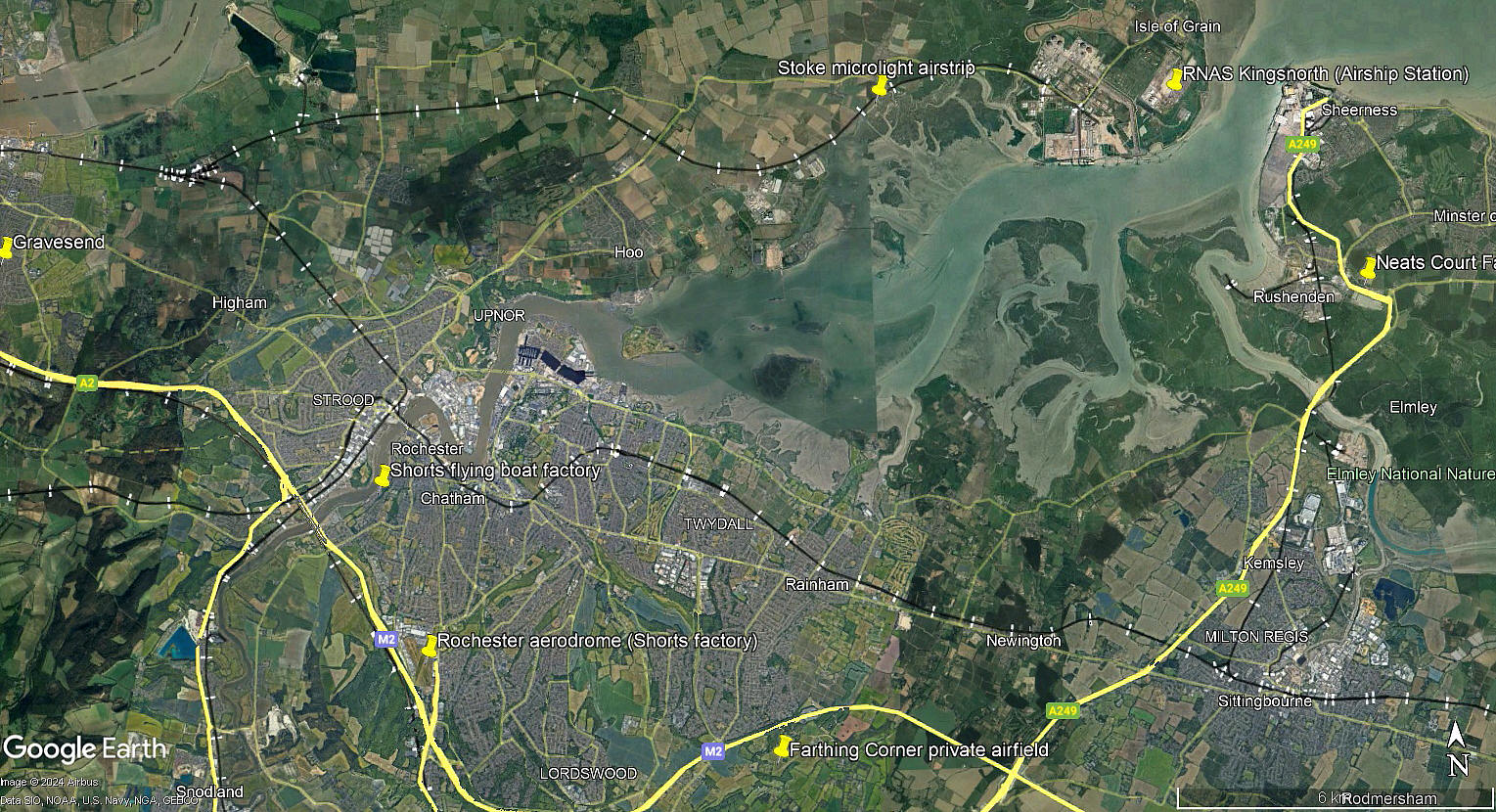

Rochester flying sites

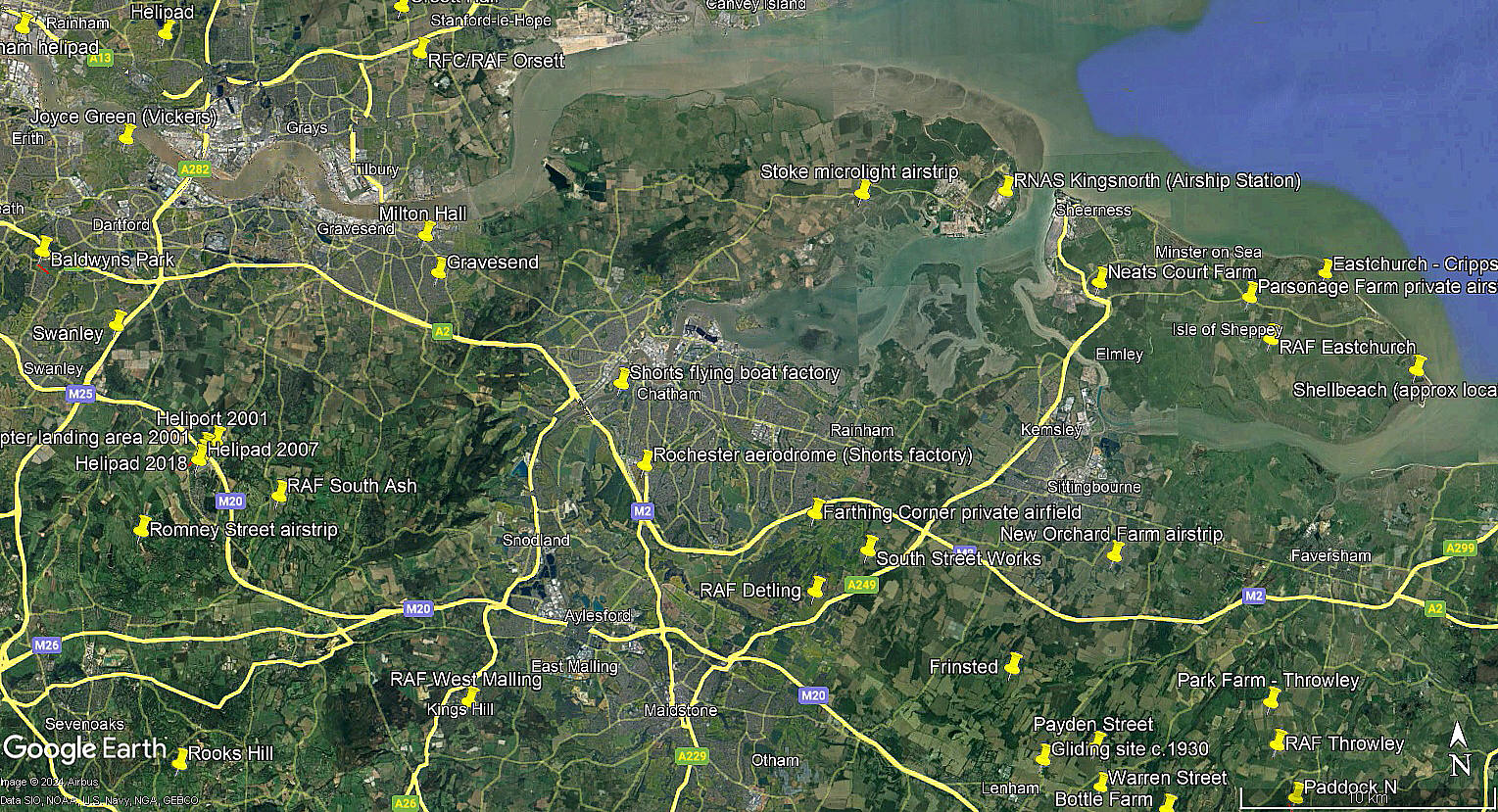

Note: This map only shows the position of Rochester town within the UK.

ROCHESTER: Early temporary flying site?

NOTES: In his book British Built Aircraft Vol.3 Ron Smith gives information about the Batchelor Monoplane built in 1910 at a site in Rochester. Presumably some flight trials took place, perhaps from a site in this area?

THE EARLY DAYS

In his excellent book, British Aviation - The Pioneer Years, first published in 1967, Harald Penrose gives us this account. "With every indication of increasing orders for seaplanes, Horace, Eustace and Oswald Short decided that it was uneconomic to transport their productions from Sheppey to the Naval Medway base for testing, so Oswald was instructed by Horace to find a new site, and presently discovered a flat ledge of Medway shoreline beneath high ground near Rochester Bridge."

"Purchasing it at waste-land price, they began building a new factory with ample room to extend along the shore."

I strongly suspect that this site was south of the Rochester Bridge? See below.

A FLYING CIRCUS VENUE

ROCHESTER was the 106th venue for the Sir Alan Cobhams 1929 Municipal Aerodrome Campaign. Starting in May and ending in October one hundred and seven venues were visited. Mostly in England, two were in Wales and seven in Scotland. This venue was almost certainly in October.

It is of course very tempting to assume they used the ROCHESTER aerodrome used by Shorts, but experience has taught me to be very wary of jumping to such conclusions. If anybody can kindly offer advice, this will be much appreciated.

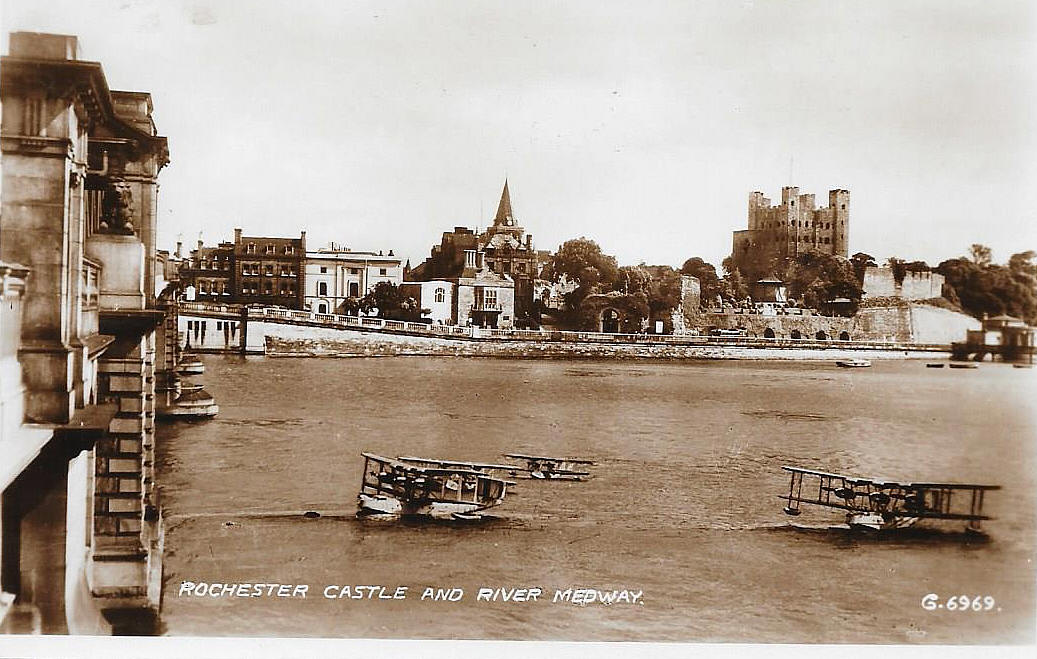

A MIKE CHARLTON MEDWAY GALLERY

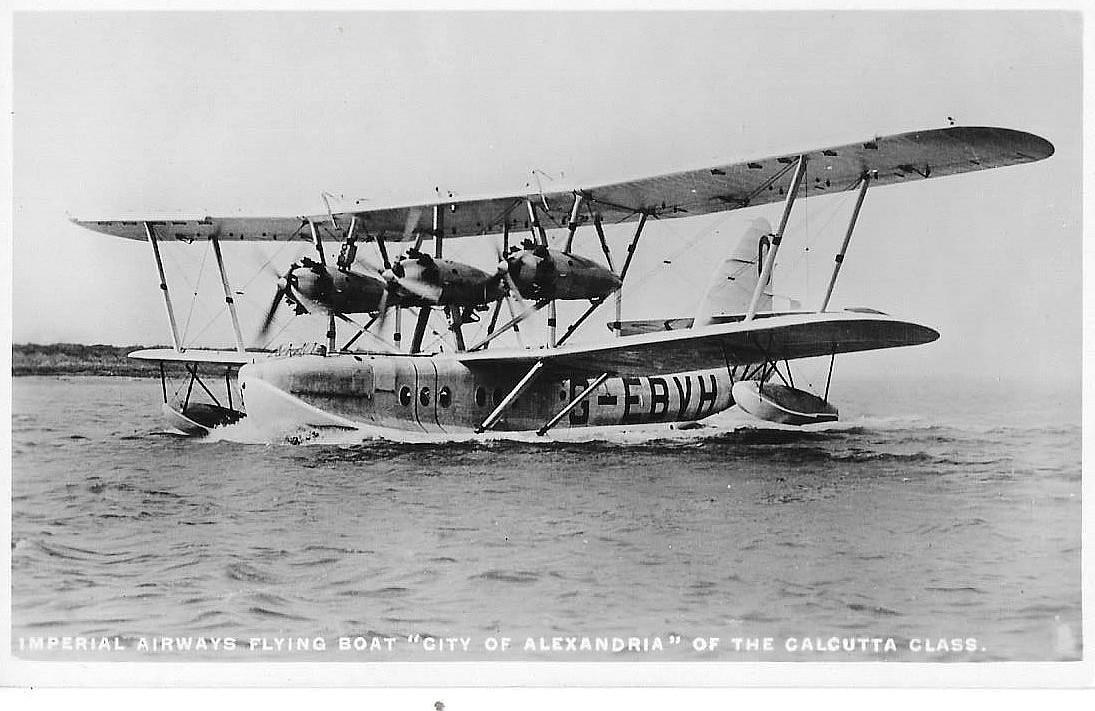

Here is a collection of flying boat pictures from postcards very kindly provided by Mike Charlton which were produced by Shorts in Rochester. He has an amazing collection, see: www.aviationpostcard.co.uk

First picture: My knowledge of this era is woefully inadequate, but I think the two three-engined flying boats might be either S.8 Kent or Rangoon types? And beyond, possibly a S.19 Singapore? Any advice will be most welcome.

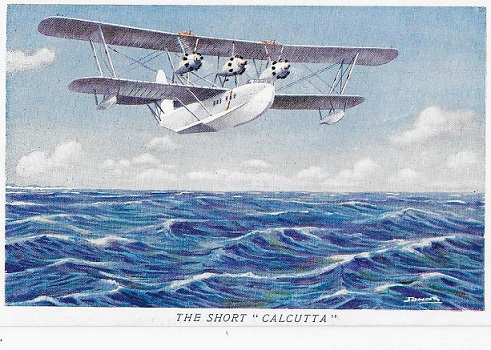

Second picture: It appears that the 11-seater Short S.8 Calcutta G-EBVH was originally N215 operated by the RAF. Registered to Imperial on the 13th September 1928 it served with them until June 1937 when it went to Air Pilots Training based in Southampton. Six months later it was broken up for spares at HAMBLE.

I suppose it seems likely, given that it was named 'City of Alexandria' that G-EBVH probably spent most of its life with Imperial in the Middle East and Africa.

Third picture: Yet another conflict of accounts?. One usually reliable source states that the 29-seater Short S.23 Empire G-ADUU was registered on the 7th October 1935. Yet the official records say it was registered to Imperial Airways on the 8th March 1937. It appears it was based in Bermuda and sank there on the 21st January 1939.

Fourth picture: The 29 seater Short S.23 Empire 'Centurion' G-ADVE was first registered on the 7th October 1935, nine months before the first example flew on the 3rd July 1936. Once registered with Imperial its base was listed as ROCHESTER. It sank at Calcutta, India, after landing on the 12th June 1939.

Fifth picture: The Short S.8 Calcutta first flew on the 14th February 1928. Seven were built:

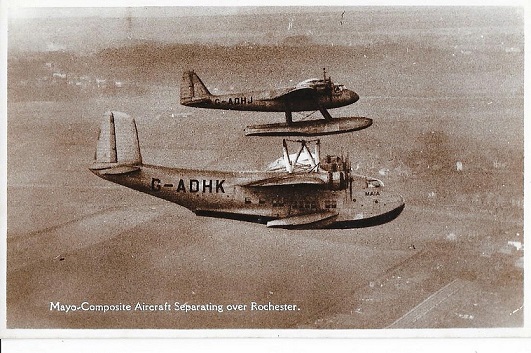

Sixth picture: More information about the 'Mayo-composite' is elsewhere in this listing. It is probably difficult today to realise just how incredibly important the quickest delivery of mail was in the development of airlines across the world. Carrying passengers was an 'add-on' feature to quite a large extent. And indeed, the 'Mayo-composite' was designed to enable mail to be carried quickly, mainly across the Atlantic.

Seventh picture: For some reason, in this artists impression, the carrier is seen as 'Calypso' which was G-AEUA. And, as far as I am aware, never involved with the 'Mayo-composite' trials.

Note: *Copyright unknown, probably no longer applicable? The local area and area views are from my Google Earth © derived database.

A MICHAEL T HOLDER MEDWAY GALLERY

We have Mike Holder, another great friend of this 'Guide', to thank for providing the following:

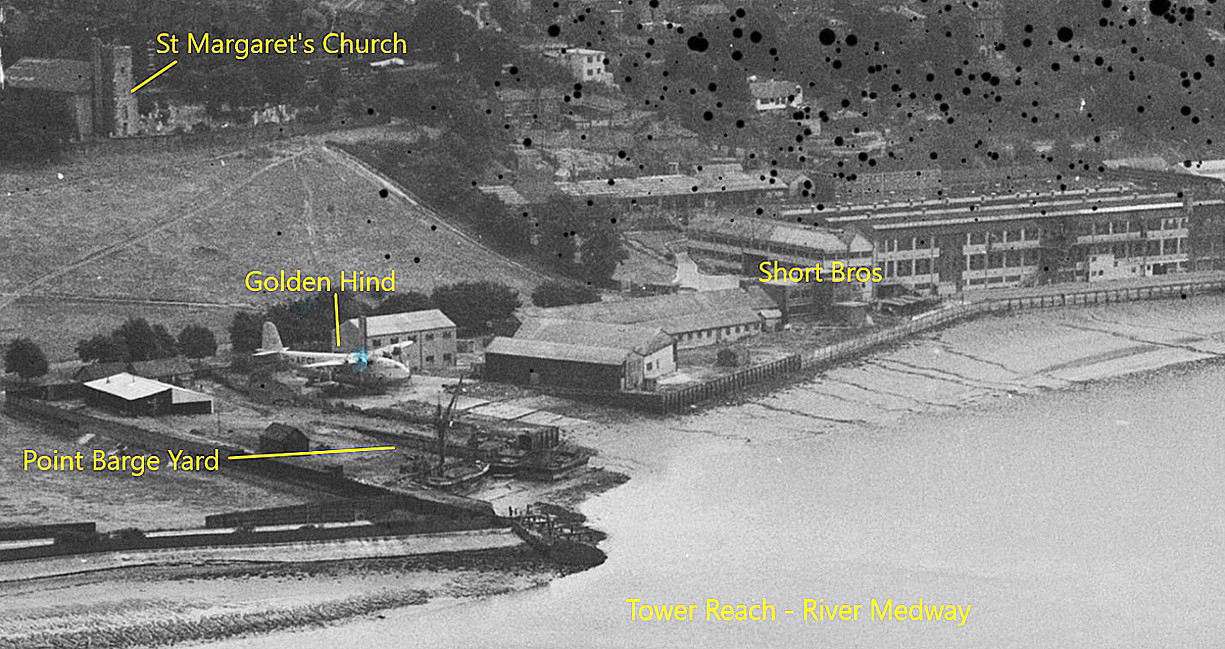

Note: The 1949 photo features G-AFCI 'Golden Hind'.

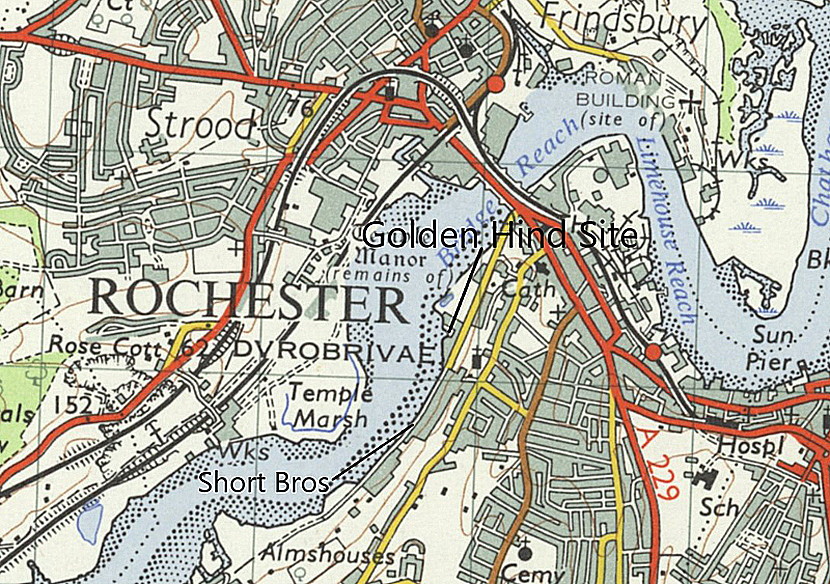

ROCHESTER:

Private Seaplane/Flying boat Station (Adjacent to factory)

(Also known as MEDWAY or RIVER MEDWAY and BORSTAL)

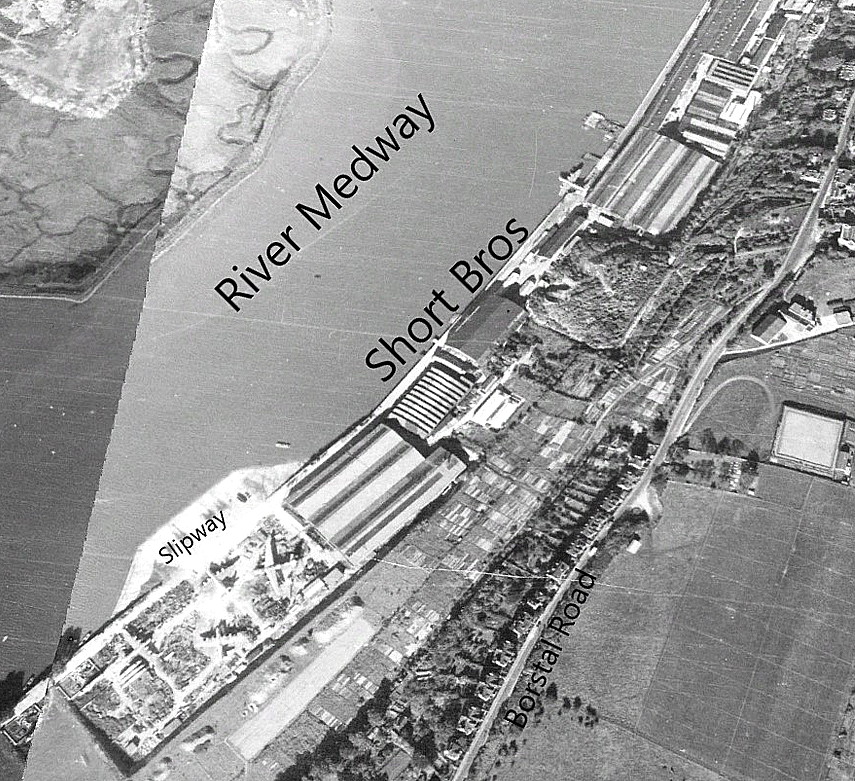

Users: Short Bros

WW2: ATA 6 FP

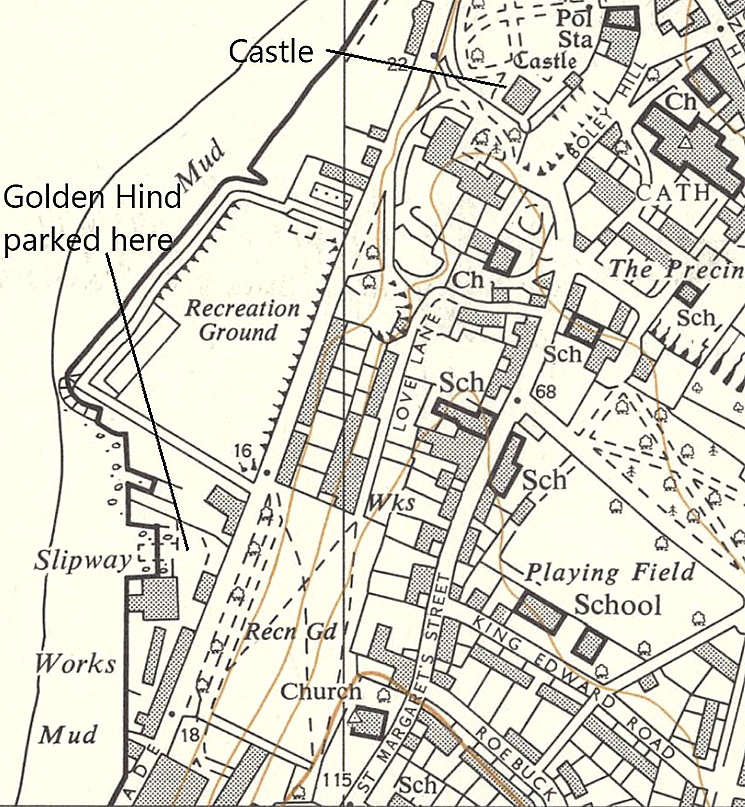

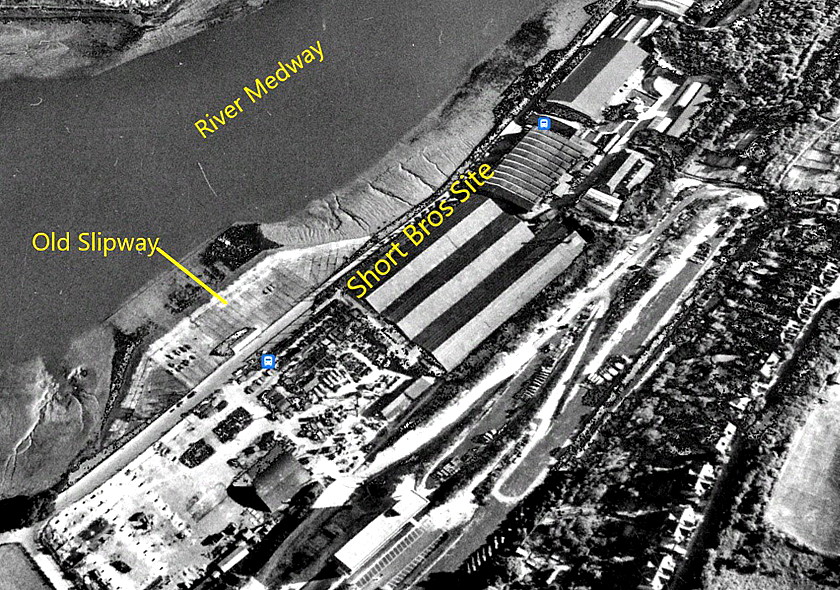

Manufacturing: From October 1913 to January 1914 Short Bros built a factory for seaplanes on the banks of the Medway, later to produce their famous flying boats. If I’ve got this correct the slipway they constructed is still in existence just N of the M2 motorway bridge on the east bank

Location: Originally on The Esplanade

It appears that another site on the River Medway, S of the Rochester Bridge and just N of the M.2 motorway was also used, with the factory co-located.

Period of operation: 1911 to 1946? Some say 1914 to 1948

NOTES: It appears that on the 1st December 1911 Lieutenant A M Longmore (RN) first landed a ‘water plane’ or seaplane on the RIVER MEDWAY - presumably near Rochester?

A PIONEERING FLIGHT

30th June 1926: Alan Cobham departed on another incredible pioneering route proving flight to Melbourne, Australia in the tried and trusted DH.50J (G-EBFO, this time fitted with floats by Short Bros), returning to land on the Thames outside the Houses of Parliament on the 1st October. Just over three months and a huge improvement I suppose (?) over his previous flight to Cape Town completed not long before.

It is often claimed, or so it seems, that this and the previous project to Cape Town were, in effect, exploratory flights for Imperial Airways. Which would appear to make a lot of sense? However, in his 'autobiography' A Time To Fly, Cobham makes no mention of any involvement, or any interest expressed by Imperial. Indeed, they were both independent projects depending initially on generous sponsorship, which, if successful would generate world wide fame and a corresponding huge amount of publicity. And this was most certainly a proven result - ending with Cobham receiving a knighthood.

Cobham, (with a lot of help of course), was clearly becoming an ace at organising long distance flights. His flight to Cape Town and back lasted from the 15th November 1925 until the 13th March 1926. Just about three months. The Australia return flight lasted from 30th June 1926 until the 1st October. Again, just about three months but with roughly a straight line distance of 10,500 miles from Melbourne compared to 6000 miles from Cape Town. Probably twice the amount of flight time in 'real' terms?

A VERY INTERESTING ASPECT

As Cobham readily admits, after deciding that a floatplane was by far the best option for the trip to Australia, he had no experience - at all! He took himself off to Rochester get some practice. As can be expected, the trip on floats was a huge learning curve, but he coped. He also makes an interesting note, which reflects my experience flying around Scotland and down to the south coast of England; "I was perfectly happy about crossing France and other land areas in a seaplane, though some people considered this an eccentic thing to do. If a forced landing became necessary, almost any lake or river would serve as a good aerodrome; and at worst, it would be less dangerous to bring a seaplane down into a field than to ditch a wheeled aircraft."

This said he was not prepared to risk flying around Australia on floats, so a wheeled-undercarriage was shipped to Darwin.

SOME THINGS DON'T CHANGE?

Some things in history don’t change much, like the hatred in some if not most Middle East factions for western culture and ideology. On the way across Iraq Cobham’s engineer, Mr Arthur Elliott, was fatally wounded when they were fired at in flight, (apparently by a Marsh Arab), whilst en route over southern Iraq to Basra, where Mr Elliott died in hospital the next day.

It appears that Cobham was so distraught he was in favour of calling the whole thing off but had so much support he then decided to continue, possibly to honour the memory of his much trusted engineer? In those days it was UK imperialism of course but for some Iraqi people, then and now, I suppose the difference between UK and US regimes hardly counts?

KEEPING GOING

Having made the decision to continue now with Sgt A H Ward as his engineer 'loaned' by the RAF, they flew from Basra to Bushire and Karachi. Then right across India by way of Bahawalpur and Delhi and Allahabad and Calcutta. They then flew via Chittagong, Rangoon and Penang to Singapore. Finally by way of Sumatra and Java to Timor, and across the water to Darwin. Cobham making no comment on any of this, as if it was just another routine affair.

Although most accounts state they reached Melbourne, it appears they actually flew onto Adelaide! It is interesting to read that Alan Cobham did not really much appreciate the adulation he and his crew received in Australia, much though it was enjoyed at the time. The whole point being that if a pretty much 'bog-standard' light aircraft and crew could now achieve this - therefore the way ahead for scheduled services with modern airliners - was very much now on the cards.

GETTING GOING

Wasn’t it simply astonishing how quickly companies like Imperial Airways could get their act together? As said, Cobham returned with his findings on the 1st of October, (using a seaplane of course), but, the first Imperial Airways proving flight to India, using a DH.66 Hercules landplane, took off from CROYDON on Boxing Day the same year.

AND MORE PIONEERING FLIGHTS

17th November 1927: Sir Alan Cobham departs on yet another epic 20,000 mile flight to survey Africa in the Short Singapore G-EBUP. Presumably finding time to get a ‘twin’ rating in between. In his autobgraphy A Time To Fly he readily admits that converting from a DH.50 on floats to a ten-ton twin-engine Short Singapore was a major learning curve in every respect.

It is sometimes reckoned that this flight was to some extent commissioned by Imperial Airways. It wasn't. They had no interest in extending their routes south of Cairo. This was a joint venture by Cobham-Blackburn Air Lines to establish an airline route to South Africa. The first sector was a short 'skake-down' flight from ROCHESTER to the River Hamble at Southampton which ended up, no fault of their own, an utter shambles.

Detained by gales and then fog, they departed to Bordeaux then via Marseilles to Corsica and Malta, where things went seriously adrift, delaying the project for several weeks, almost finishing the project for good. But they overcame the problems flying to Torbruk, Aboukir and Alexandria where a major plague was afflicting Egypt. The next stage involved many complications and delays. Eventually they left Aboukir and arrived in Khartoum.

From Mongalla they flew to Butiaba on Lake Albert and then to Entebbe. Cobham noting that their heavily laden Singapore could take off perfectly well at great heights and in high temparatures. An aspect that plagued many other types in years to come. The furthest points on this trip were Port Bell near Kampala and Mwanza. The return trip was around the western 'rump' of Africa calling in at Lagos, Takoradi, Abidjan and Freetown in Liberia. Then to Bathurst and Port Etienne, more problems and Las Palmas with a serious fuel leak. Then back to more familiar places, Casablanca, Gibraltar, Barcelona and Bordeaux. As said, reading a fuller account in A Time To Fly is highly recommended.

After 82 take-offs and alightings and 330hrs flying, he arrived back in PLYMOUTH on the 31st May 1928. He then proceeded to tour the UK and show off this aeroplane.

THE UK TOUR

Here again the full story is very complicated and far from straightforward with some serious problems to resolve regarding the Singapore. But, incredibly, they took off from ROCHESTER for HULL on the 4th June. As Cobham says, "..none of us looked very healthy. I suspect that most or all of us had malaria." And it didn't get any better as the trip progressed. Nevertheless they perservered; From HULL to NEWCASTLE, EDINBURGH, GREENOCK, BELFAST, LIVERPOOL, SOUTHAMPTON and back to ROCHESTER.

They were fêted all the way, with a grand ceremonial luncheon when they completed the Tour on the 11th June.

THE WORLD HAD CHANGED

Despite assurrances that Cobham's airline would have the African routes, (which they had poineered), Imperial started flexing its political muscles. And Cobham's airline was thrust aside. Having no choice but to accept what was left on offer, from the 22nd July to 31st August 1931, Alan Cobham flies the Short Valetta floatplane G-AAJY for an African lakes survey flight. For the benefit of Imperial Airways.

Cobham makes a couple of interesting observations about the Valetta. He found it pleasant and easy to fly, even though the drag of the big fuselage meant that the third or central engine was practically useless. Had no flight testing been carried out? Probably not in those days, or certainly not in a way we would recognise today.

But, Cobham had recommended that the Valetta was fitted with water rudders on its floats. And what a vast improvement this made. What I think is well worth mentioning in this chapter of A Time To Fly are Cobhams comments, such as: "I may have been hyper-sensitive, just at that time, to the chronic stupidity of politicians and officials and civil servants. But if I was, I can hardly blame myself." He gives the example of the two airships - the R.100 and R.101. The latter, the government supported type being totally unsuitable, untested and overladen. It came to grief on its maiden flight to India at Beauvais in France on the 5th October 1930.

One can only imagine what Cobham would have made of 'Brexit', when so many people from the Prime Minister down, clearly lacking a basic education, have failed to realise that you cannot square a circle. You can hammer away as long as you want, but a square peg will not fit into a circular hole. Its either remain or leave. Either way the damage has been done, (2019), and the results will remain for decades to come.

THE FIRST FLIGHT OF A TRUE CLASSIC

On the 4th July 1936 the first Shorts S.23 ‘C’ Class ‘Empire’ flying boat G-ADHL made its first flight. A type which has gone down in British aviation history at least as being at the zenith of luxury and flying excellence. Incredible then that those ‘hey-days’ barely lasted for three years!

These services were curtailed by WW2 being declared. However, after being stripped down, the 'C' Class flying boats were in regular use, mainly it seems flying the 'Horse-Shoe' route to Australia via Lisbon and West and Central Africa. See extra notes below.

CIRCLING HALF THE WORLD

In his book Britain’s Greatest Aircraft Robert Jackson relates: “The first eastbound proving flight by an Empire Boat was made on 22 October 1936, when Canopus flew from Rochester to Alexandria via Caudebec, Bordeaux, Marseille and Rome. The return trip was started on the 30th, the aircraft flying via Athens, Mirabella and Brindisi.

On 13 December, G-ADHM Caledonia set out for India with five and a half tons of Christmas mail on board, carrying a similar load on the return trip. On the homeward flight, the pilot Captain Cumming, left Alexandria on 21 December and flew the 1,700 miles to Marseille non-stop in eleven and one-quarter hours. On the following day, he flew direct across France to land at Southampton after four and a half hours.”

He then goes on to mention; “ Regular flights from Marseille to Alexandria via Rome were started on 4 January 1937, using G-ADUW Castor, and on 12 January a through service was started between Alexandria and Southampton with G-ADUT Centauras. G-ADUX Cassiopeia also joined the service on 26 January, and on 18 February G-ADHM Caledonia flew the whole 2,200-mile distance from Southampton to Alexandria non-stop in thirteen hours.

By the end of 1937 twenty-two Empire boats were in service with Imperial Airways, and two more, VH-ABA Carpentaria and VH-ABB Coolangatta were also supplied to Qantas for use on the Singapore - Brisbane sector. Early in the following year the Australians received a third aircraft, VH-ABC Coogee, which was transferred from the British register.”

THE 'C' CLASS FLEET

The fleet of S.23, S.30 and S.33 C Class ‘Empire Boats’ is as follows, and I trust, is complete?

There are of course various web-sites which assist in the research.

THE S.23s

S.23 G-ADHL Canopus S.23 G-ADHM Caledonia S.23 G-ADUT Centaurus

S.23 G-ADUU Cavalier S.23 G-ADUV Cambria S.23 G-ADUW Castor

S.23 G-ADUX Cassiopeia S.23 G-ADUY Capella S.23 G-ADUZ Cygnus

S.23 G-ADVA Capricornus S.23 G-ADVB Corsair S.23 G-ADVC Courtier

S.23 G-ADVD Challenger S.23 G-ADVE Centurion

S.23 G-AETV Coriolanus (later Qantas VH-ABG) S.23 G-AETW Calpurnia

S.23 G-AETX Ceres S.23 G-AETY Clio S.23 G-AETZ Circe

S.23 G-AEUA Calypso

S.23 G-AEUB Camilla (Became VH-ADU with Qantas in August1942)

S.23 G-AEUC Corinna S.23 G-AEUD Cordelia

S.23 G-AEUE Cameronian (Originally named Cairngorm)

S.23 G-AEUH Corio (later Qantas VH-ABD Coolin)

S.23 G-AEUI Calpe (later Qantas VH-ABE Coorong)

S.23 G-AEUO Cheviot (later Qantas VH-ABC Coogee)

S.23 G-AEUT Corinthian (Originally named Cotswold)

S.23 G-AFBJ Carpentaria (later Qantas VH-ABA)

S.23 G-AFBK (later Qantas VH-ABB Coolangatta)

S.23 G-AFBL (later Qantas VH-ABF Cooee)

THE S.30s

S.30 G-AFCT Champion S.30 G-AFCU Cabot S.30 G-AFCV Caribou

S.30 G-AFCW Connemara S.30 G-AFCX Clyde

S.30 G-AFCY Captain Cook (ZK-AMA Aotearoa)

S.30 G-AFCZ Canterbury later Clare and possibly, later still, Australia

S.30 G-AFDA Cumberland (ZK-AMC Awarua)

S.30 G-AFKZ Cathay

S.33 G-AFPZ Clifton (later VH-ACD with Qantas in June 1943)

S.33 G-AFRA Cleopatra

S.33 G-AFRB (Not named and scrapped in 1943)

Australian examples operated by QANTAS:

(Queensland and Northern Territories Aerial Services):

S.23 VH-ABA (ex G-AFBJ Carpentaria)

S.23 VH-ABB Coolangatta (ex G-AFBK)

S.23 VH-ABC Coogee (ex G-AEUO Cheviot)

S.23 VH-ABD Coolin (ex G-AEUH Corio)

S.23 VH-ABE Coorong (ex G-AEUI Calpe)

S.23 VH-ABF Cooee (ex G-AFBL)

S.23 VH-ABG (ex G-AETV Coriolanus)

New Zealand examples operated by TEAL: (Tasman Empire Airways Ltd)

S.30 ZK-AMA Aotearoa (G-AFCY Captain Cook)

S.30 ZK-AMC Awarua (G-AFDA Cumberland)

THE FLYING BOAT ROUTE EXPANDS

Robert Jackson then relates: “ In September 1937, G-AETX Ceres made a survey flight over a new route from Alexandria to Karachi, the aircraft flying via the Dead Sea, Habbaniyah and Sharjah, and a regular service started the following month by G-AEUA Calypso. On this occasion, mail was flown from Southampton to Alexandria by G-AETY Clio, the journey being continued by Calypso, but on the return service G-AEUB Camilla made the entire trip from Karachi to Southampton.”

The sheer speed with which these services were being launched might seem quite astonishing today, but of course nearly all the routes crossed areas shown as pink on maps – under the control of the British Empire. Hence these flying boats were called ‘Empire Boats’. Even so, given the methods of supply available, the sheer logistics alone must have been both a daunting and admirable exercise.

IT GETS BETTER

And, it gets even better – to quote Robert Jackson again: “On 15 November 1937, G-AEUD Cordelia left Karachi to make a survey flight to Singapore, where she arrived six days later, and on 3 December G-ADUT Centaurus left Hythe to carry out a survey flight all the way through to New Zealand, completing the last leg from Sydney to Auckland on 27 December. This sector of the route was to be operated by Tasman Empire Airways Ltd, formed jointly by the British, Australian and New Zealand Governments, and three Empire Boats were allocated for this purpose.”

It appears, according to Robert Jackson, that the start of regular services between Australia and New Zealand didn’t commence until 1940, and this of corse was during WW2. However, in 1938 Qantas began a Singapore to Darwin service, soon extended to Sydney.

IN AND ACROSS AFRICA

In Africa, to quote Robert Jackson yet again: “On the Cairo – Cape Town route, the Imperial Airways workload was shared between Handley Page HP.42s and Armstrong Whitworth Atalantas until 1937, when the first Empire Boats joined the service. In the summer of 1937, the Empire Boats started an air mail service to Durban, and at the same time one of them – G-ADUV Cambria, commanded by Captain Egglesfield – made a 20,000-mile survey of the African routes, the task being completed on 4 June.”

A LESSON LEARNT

A by-product I had not expected to learn about when starting my research into British flying sites was the two-fold appreciation of both aviation industry advances and social history. Talking generally regarding the aircraft, I had not fully realised that when the ‘Empire Boats’ came into service the RAF front-line fighters were biplanes and the bomber types were, quite frankly, utterly useless. The later monoplane fighters, the Hurricane and Spitfire were only just coming into service, along with the Whitley, Hampden and Wellington bombers.

Regarding the social aspects there came the realisation that the very rich, and those in power, are not in the slightest affected by economic conditions applying to the country at large. And it was mostly this class of person who could afford to fly.

It came as quite a surprise to realise that the first flight of an ‘Empire Boat’ in July 1936, offering hitherto levels of luxury undreamt of previously, was followed in October with the starving Jarrow workers march to London. Quite obviously the ‘Great Depression’ was having little if any effect to those with wealth, privilege and status. This said it is claimed that the back-bone of the commercial success of the Empire Boats depended mostly on the carriage of mail.

A FLAWED CONCEPT

It is often stated that war-time conditions give rise to the most significant technological advances – but this is obviously a flawed and far too simplistic concept. As already stated, when the first ‘Empire Boat’ first flew in 1936 most of the front-line RAF fighters and bombers were biplanes. By comparison the Short 'C' Class flying boats were incredibly advanced and the RAF Bomber Command (as it later became) had nothing even remotely comparable.

When in the early to mid 1930s the British began to realise that another war with Germany was inevitable, (although many in high positions were in denial), aircraft manufacturers set to designing a completely new breed of fighters and bombers to face the task. The Hawker Hurricane first flew in November 1935 and the first Spitfire in March 1936. Only three or so years before WW2! When it came to the bombers the Armstrong-Whitworth Whitley first flew in March 1936, and the Handley Page Hampden and Vickers Wellington both first flew in June 1936 - and these were all only twin-engine medium bombers.

Incidentally, whilst on the subject, these three British bombers are invariably regarded as being very inferior to the equivalent German bombers. A complete myth and utter rubbish - in many ways they were superior. And, this is not just my opinion based only on sentiment - compare the figures.

And yet here we have, in the 'C' Class, a large four-engine monoplane with a speed, range and carrying capacity that the RAF couldn't equal for several years later! Perhaps it should come as no surprise that the now much maligned Short Stirling, the first of the heavy four-engine British bombers was also designed and built by Short Bros, and, in its day it was a revelation. It needs to be borne in mind though that the first Stirling flew in May 1939.

THE PACE OF PROGRESS

The first air race to Australia took place in 1919 (won by a Vickers Vimy), and yet, just eighteen years later, the ‘Empire Boats’ were setting standards of luxury and a superb flying experience which still, in some respects, cannot be fully equalled today. For example, you won't find too many B.747 or A.380 crews prepared to give you a low level cruise along the river Nile, etc, etc, etc. Obviously it is quite difficult to compare like-with-like in such matters.

THE FINAL STAGES, A WAR CAREER

It seems fitting to mention the remaining career stages of the Empire Boats and once again this account by Robert Jackson sums it up rather well: “The Empire Boats had an eventful wartime career, flying much of the time on sectors of BOAC’s ‘Horseshoe Route’ via East Africa and India to Australia. Two S.30s and two S.23Ms (the ‘M’ denoting Military) served with No.119 Squadron RAF for a few months in 1941, operating from Pembroke Dock, and three were lost during the war.

Thirteen boats survived, being refitted with Pegasus 22 engines, and continued to serve for a short period after the war, but all had been withdrawn by the end of 1947.” Here again, what a very great pity that nobody thought to preserve even one example.

AMAZING?

It now seems quite amazing to me today, (or certainly did when first written up several years ago), but it does seem the prototype S.25 Sunderland, (a design based on the ‘C’ Class), first flew here on the 16th October 1937! Much has been said and written about how unprepared the British Government and the military forces were for WW2, (as mentioned previously) but it also seems pretty clear that many individuals, private companies, corporations and indeed many within the RAF and government departments were planning well in advance. Well worth repeating I think.

A NEW DEPARTURE

The Shorts company were also planning advances in long distance trans-oceanic flights and on New Years Day 1938 the Short-Mayo Composite G-ADHK Maia and G-ADHJ Mercury made its taxiing trials on the Medway. The first flight of the combination was made on the 19th January with the first mid-air seperation in flight occurring on the 6th of February. In so many ways a brilliant idea and solution, but it was of course also a typical sort of British compromise. Barely practical and doomed to fail commercially, with hindsight of course.

The idea was that the bigger flying boat would take the smaller aircraft so far, and release the float-plane to finish the journey.

A TABLE OF SHORT BROS TYPES

In his excellent series of books British Built Aircraft, in Vol.3 Ron Smith provides a table of Shorts types that first flew from the two ROCHESTER sites from which this abbreviated version is mostly derived. In this table Ron Smith puts the Silver Streak G-EARQ. This was a remarkable aircraft being the first example of metal stressed skin construction, in the UK, but it was a landplane and, it appears, first flew at GRAIN (?) in 1920. He also includes the Satellite G-EBJU, another landplane which competed in the Daily Mail ‘Trials at LYMPNE.

Date Serial or Reg. Type Notes

19.04.21 N120 N.3 Cromarty, Short’s first flying boat

07.11.24 G-EBKA S.1 Cockle All-metal single-seat flying boat

05.01.25 N177 Felixstowe F.5 Metal hull version

06.04.26 G-EBMJ S.7 Mussel

17.08.26 N179/G-EBUP S.19 Singapore I

Note: Used by Sir Alan Cobham for the 1929 flying boat survey of Africa

14.02.28 G-EBVG S.8 Calcutta Flown by Imperial Airways

17.05.29 G-AAFZ S.7 Mussel II

27.03.30 N246 S.19 Singapore II With 4 x Rolls-Royce XII engines

21.05.30 G-AAJY S.11 Valetta For use by Sir Alan Cobham

24.09.30 S1433 S.8/8 Rangoon Military version of the Calcutta

24.02.31 G-ABFA S.17 Kent

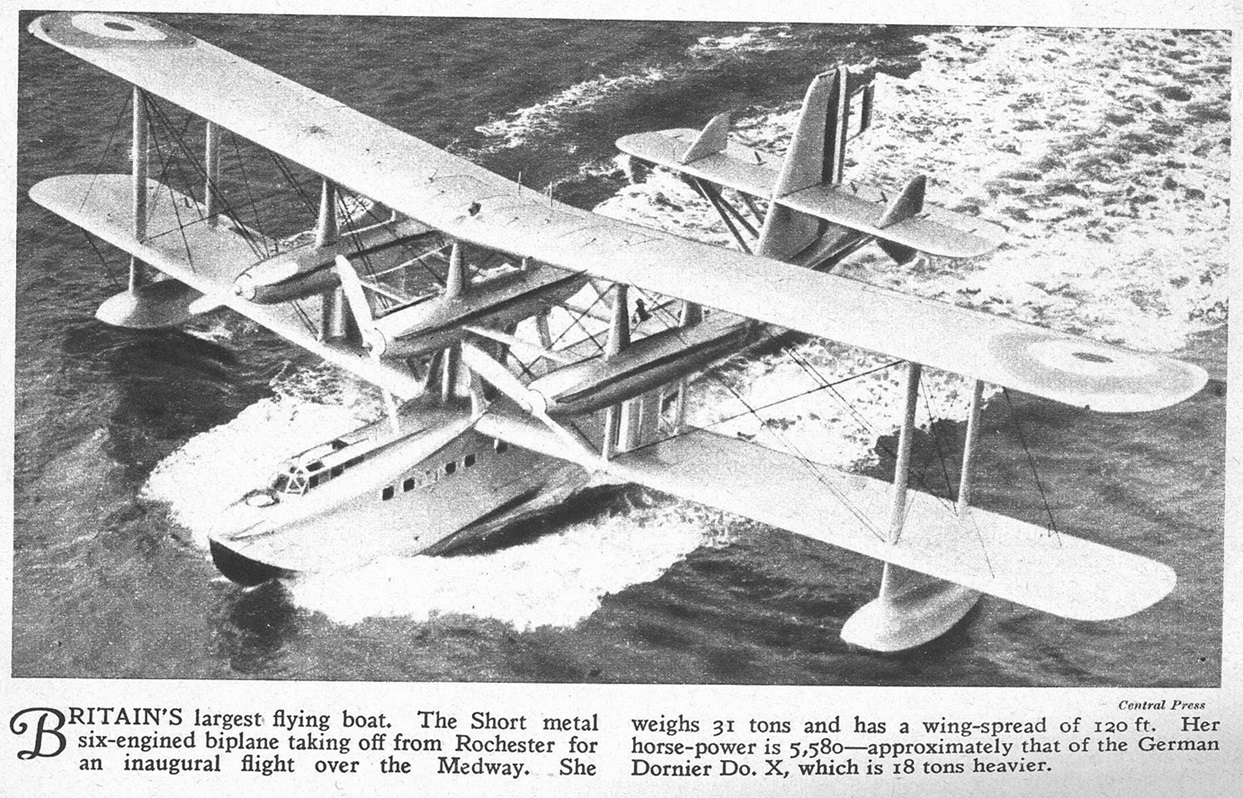

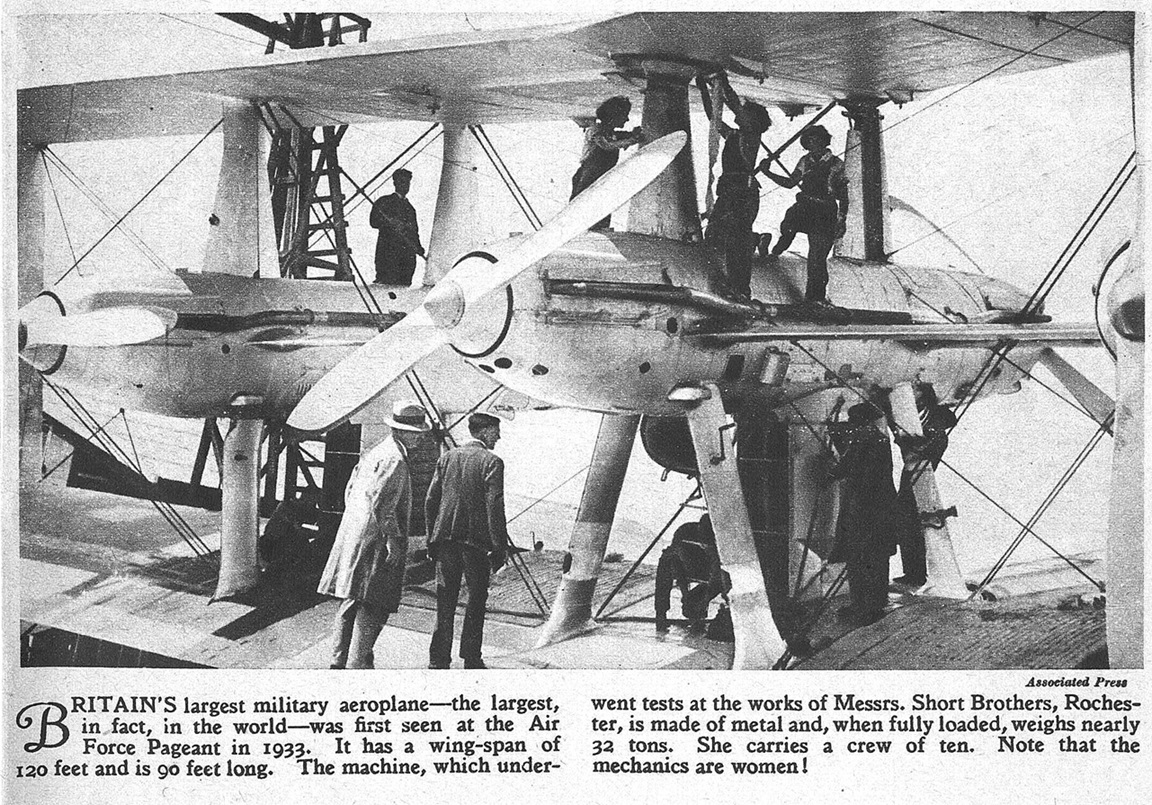

30.06.32 S1589 S.14 Sarafand A military flying boat with six engines

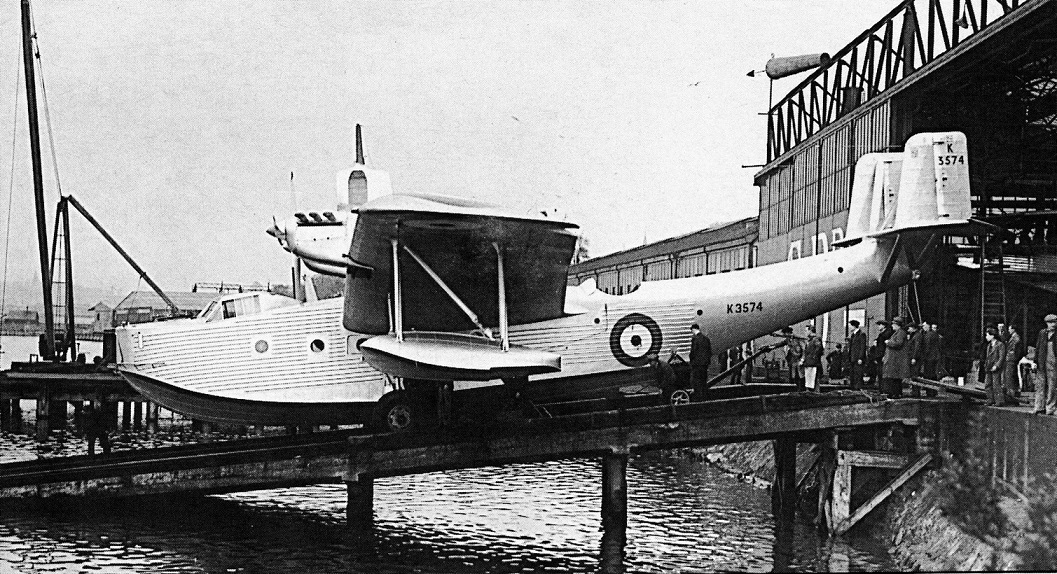

30.11.33 K3574 S.18 Knuckleduster

15.06.34 K3592 S.19 Singapore III 37 built for the RAF

22.10.35 VT-AGU S.22 Scion Senior Seaplane version

03.07.36 G-ADHL S.23 Empire

Note: The first of the classic Empire types for Imperial Airways

27.07.37 G-ADHK S.21 ‘Maia’

Note: The ‘bottom half’ of the Short Mayo composite ‘piggy-back’ project

05.09.37 G-ADHJ S.20 Mercury

Note: The ‘top half’ of the Short Mayo composite ‘piggy-back’ project

16.10.37 K4774 S.25 Sunderland

Note: Without any doubt the most famous British WW.2 military flying boat

28.09.38 G-AFCT S.30 Nine built

21.07.39 G-AFCI S.26 One built, the Golden Hind?

April 1940 G-AFPZ S.33 Last version of the S.23 Empire

30.08.44 MZ269 S.45 Seaford Sunderland development

14.12.44 DX166 S.40 Shetland Another Sunderland development

28.11.45 ML788/G-AGKX S.25 Sandringham

A COMMENT

Today of course when nostalgia often rules the roost, the Empire flying boats are invariably seen as the ‘classsic’ British flying boat design. In so many ways they were of course but their safety record is not exactly squeaky clean, especially when compared to the Handley Page HP.42s landplanes for example which had an exemplarary safety record. There is something to be explained here about the HP.42 type. Many people today cannot understand why Imperial Airways opted for such an antiquated design - as it is usually seen - when much faster and 'modern' designs were available.

The reason is quite straightforward, the HP.42 was, although an airliner of considerable size, in effect what we would describe today - for light aircraft especially - a STOL machine (Short-Take-Off-and-Landing). Many of the so-called 'airports' they used, certainly in the Middle East, were nothing more than rough strips - for which the HP.42 was ideally suited.

WHAT WAS THE 'TRUE' CLASSIC BRITISH FLYING BOAT?

The argument can rage forever of course and will never be won. My heart tells me it has to be the 'C' Class 'Empire' flying boats. But reason seems to suggest that my nomination for the ‘classic’ British flying boat would be the Sunderland and I really do believe that RAF Coastal Command Short Sunderland crews deserve to be far better regarded and appreciated.

LETS FACE IT

It appears that in total around 1,157 Sunderlands were built and typically final figures appear to vary. Exactly how estimates of production numbers of such a huge machine can be open to question is a subject that totally bewilders me.

Ron Smith in his series of books, British Built Aircraft states in Vol.3 that 749 were built at ROCHESTER, 133 in Belfast (SYDENHAM), and 35 at Windermere. This site was WHITE CROSS BAY on Lake Windermere in WESTMORLAND. A further 240 were built at DUMBARTON on the north side of the River Clyde west of Glasgow in DUNBARTONSHIRE.

And so, if numbers alone win the argument, which is I think a convincing position to adopt, the Sunderlands wins - hands down.

ANOTHER MEDWAY ASPECT

It also appears that Percival Aircraft Ltd used the River Medway when testing the Percival 6 floatplane X1/CF-EHF destined for the Hudson Bay Co in June 1946. Did Percival share the Short Bros facility? If not, yet another twist in the history of this area which needs to be explored. Can anybody kindly tell us more?

AIRCRAFT TYPE NUMBER SEQUENCES - FOR FIRST FLIGHTS

I often find it interesting to note that first flight dates for various types rarely if ever follow in sequence, hardly surprising of course due to development and design issues. But, I am often surprised at the time lag, even in the 1920s and 30s which had a reputation for producing new types from a ‘back-of-fag-packet’ concept to first flight often within months.

For example: Could it be that on the 17th September 1947, the Short S.40 Shetland G-AGVD was the last of the Short types to fly off the River Medway site? Or - am I correct in thinking this was the last ‘first flight’ of a Short type taking off from this location?

It does appear that the very last flight of a Short flying boat from the RIVER MEDWAY factory was a Short S.45 Solent in April 1948. This was G-AHIY and the last Solent 2 for BOAC. Further Solent 3 and Solent 4 types were built at SYDENHAM in Belfast, Northern Ireland.

A REDUNDANT CONCEPT?

Much is now made about how the British clung onto the flying boat concept long after they became a redundant concept. To quote Ron Smith, “The Sunderland, Hythe, Sandringham and Solent were to provide BOAC and Aquila Airways with the backbone of their long distance fleets in the immediate post-war years, until succumbing to the superior economics of such types as the Constellation, Stratocruiser and DC-6.” This is certainly the generally held opinion but in many ways utter bunkum, the American types needed airports to be built, whereas flying boats require just a jetty and a handful of buoys.

Both require terminal buildings, maintenance facilities etc. In many cities around the world a water landing site is much closer to the city centre than an airport and generally speaking, by it’s very nature, does not inflict anywhere near as much noise nuisance. And of course, the British had the faciilties more or less in place. For example, elsewhere in this 'Guide' I have explained that if Bristol hadn't let Saunders-Roe down by failing to provide them with suitable engines, the Saunders-Roe Princess, far from being the total failure as it is invariably described as being, was a long-haul airliner with considerable potential, far superior to the American landplane airliners at that time.

PUTTING INTO PERSPECTIVE PERHAPS?

By this stage in history, throughout much of the world, American interests, “the new Colonial power” having 'won' WW2 in most respects, and succeeding in putting the Soviet Russian ‘empire’ into a fortress mentality, ruled the roost and they decided flying boats were most certainly against their interests. Quite why they took this stance is somewhat hard to understand as the Americans had a splendid tradition of building first-class flying boats.

Then again perhaps hardly surprising as the utterly brilliant Saunders-Roe Princess must have really put the wind up them? It was in many respects, the forerunner of the Jumbo Jet concept.

DIVERSIFICATION

Ron Smith makes a very important point regarding the 1920s and 30s which probably applied to many aircraft manufacturers? These were lean times for most so a degree of diversification was needed. Short Bros, at face value a most successful company in aviation, also built motor boats, lifeboats, electric canoes and even bus bodies.

It came as a sort of delayed shock, more of a limp surprise really, to realise that the ‘hero’ aviation companies of my youth were actually concerned with manufacturing first and foremost. Making aircraft may have been their first love and priority, but keeping the factory going overcame any prejudice.

LAST BUT NOT LEAST

Mr Graham Frost, a great friend of this 'Guide', has discovered that the Royal Geographical Society had, from new it seems, a de Havilland DH.60X Gipsy Moth Coupe, G-AAUR, which was a seaplane. Based according to offical records at Rochester. We do not know exactly where on the River Medway it was based, or indeed if it was fitted with a single float or twin floats - both options being available. The 'Coupe' designation shows it was fitted with an enclosed canopy, that type of seaplane being built mainly for export.

I suppose it is quite possible it was transported abroad from time to time? It was registered 05.03.30 until? Perhaps Short Bros offered it sanctuary? With folding wings it could be easily tucked away in a corner of a hangar. Later, in February 1933 it was converted back to being a standard landplane DH.60G Gipsy Moth, (no 'Coupe' fitted presumably?), and re-registered G-ACCY. I can find no record of it after 1933 until it appeared registered to the Redhill Flying Club on 07.02.35. It crashed at Redhill on the 20th June 1938.

A COUPLE MORE PICTURES

In August 2024 Mr Ed Whitaker kindly loaned me his copy of The Pageant of the Century published in the mid 1930s, which he had found in a car boot sale. It contained many pictures I had never seen before, and these are two examples. Indeed, the Short S.14 Sarafand, (S-1589), is not well known today. But, in its day, as a 'proof of concept' experimental one-off type, it was exceptional and flew quite well.

The captions claim it was the largest flying boat in the world. It was not, that claim to fame in that era belonging to the Dornier Do.X. the Short S.14 being a rival, and second largest. However, this design by Shorts was superior in that it had pretty much the same power with its six engines, compared to the twelve engines, (British Jupiter engines), on the Do.X, and was considerably lighter. It appears the Dornier weighed 28,250kg empty whereas the S.14 weighed 20,293kg. That difference in weight probably accounting for, in large part, the Dornier having a claimed top speed of 130mph against the S.14s 150mph, despite being a biplane.

We'd love to hear from you, so please scroll down to leave a comment!

Leave a comment ...

Copyright (c) UK Airfield Guide