Vauxhall Gardens

Note: I assume this map more or less corresponds with the 19th century site?

VAUXHALL GARDENS: Popular balloon launching site

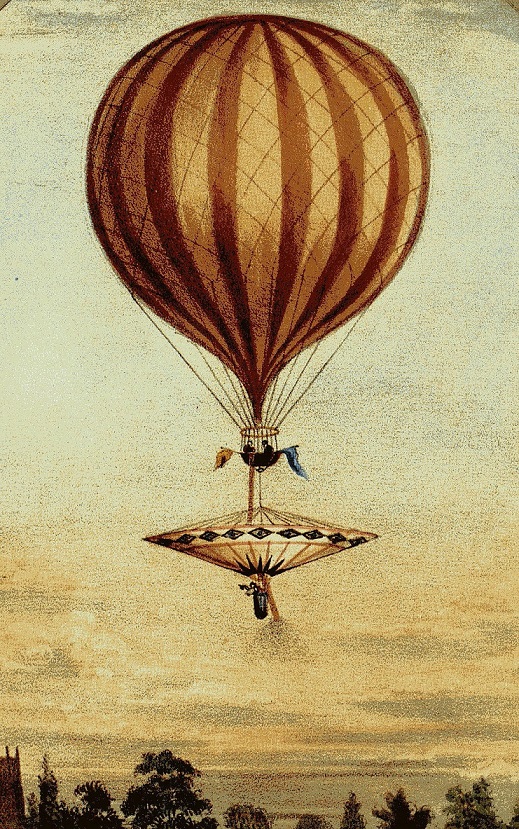

Note: The caption for this reads; "The Ascent of the Royal Nassau Balloon from Vauxhall with the Parachute attached".

Period of operation: 1816 to 1838 only? (Probably a much longer period?)

NOTES: I discovered this account of an ill fated parachute descent which departed here in 1817 in the book Flying’s Strangest Moments by John Harding which I think is worth quoting in full: “Robert Cocking was a professional watercolourist and amateur scientist who spent many years developing an improved design for a parachute. The great defect of the then standard umbrella-shaped parachute was its violent swinging during descent. Cocking calculated that if the parachute were made conical (vortex downwards) this oscillation could be avoided; and if it were made of sufficient size, there would be resistance enough to check too rapid a descent.”

“It was not until 1817 that Cocking had an opportunity to make his jump. He convinced the owners of a balloon, the ‘Royal Nassau’, that a parachute jump was just the sort of publicity they needed; it did not seem to bother them that Cocking had no experience whatever in parachuting or that he was 61 years old at the time. He built a parachute in a funnel shape and attached a bucket underneath in which he could ride. The trial was planned for take-off from Vauxhall Gardens. There were worries about the safety of Cocking’s contraption, however, and as the hour approached, the proprietors of the Gardens did their best to dissuade the inventor, offering to take the consequences of any public disappointment. He was undeterred and, at around six in the evening, Mr Green the balloonist, accompanied by a Mr Spencer, a solicitor, entered the balloon car, which was let up about forty feet so that the parachute could be fixed below.”

My note: As you will see from the two entries below and elsewhere in this Guide this “Mr Green, the balloonist” was almost certainly the Charles Green who throughout much of the 19th century was one of, if not the most celebrated British aeronaut. I somehow doubt it was simply by chance that he chose a solicitor to come along for the ride?

THE ASCENT

To return to the story: “A little later, Mr Cocking, casting aside his heavy coat and cheerfully downing a glass of wine, entered his parachute amid loud cheers with the band playing the national anthem. The balloon and aeronauts above, and himself in his parachute swinging below, rose in the gathering dusk out of view of the Gardens. The aeronauts, (My note: There was only one aeronaut on board…Mr Green), experienced a good deal of difficulty in rising to a suitable height, partly due the resistance to the air offered by the expanded parachute, partly to its weight.”

My note: I cannot see any reason why “resistance to the air” could possibly have had anything to do with this, balloons in flight, (or anything hanging off them), offer almost nil if any measurable resistance to the air. The relative inability of the balloon to climb was surely purely a weight issue.

THE DESCENT

“Cocking had planned on reaching 8,000 feet but when the balloon reached 5,000 feet, over Greenwich, Green called out that he would be unable to ascend to the requisite height if the parachute was to descend in daylight. Green said later, ‘I asked him if he felt quite comfortable, and if the practical trial bore out his calculation. Mr Cocking replied, “Yes, I have never felt more comfortable or more delighted in my life,” presently adding, “Well, now I think I shall leave you.” I answered, “I wish you a very ‘Good Night!’ and a safe descent if you are determined to make it and not use the tackle” [a contrivance for enabling him to climb up into the balloon if he desired]. Mr Cocking’s only reply was, “Good-night, Spencer; Good-night, Green!”

'Mr Cocking then pulled the rope that was to liberate himself, but too feebly, and a moment afterwards more violently, and in an instant the balloon shot upwards with the velocity of a sky rocket.’ Mr Harding then relates; “As soon as it was released, it was obvious that Cocking had neglected to take one thing into account: the weight of the parachute. The entire apparatus weighed 250 pounds, roughly ten times the weight of a modern parachute." My note: The weight of the parachute is not the issue, it is the size of the envelope required.

“Cocking’s parachute descended swiftly for a few seconds, but still evenly, until suddenly the upper rim seemed to give way, the whole apparatus collapsed (taking the form of an umbrella turned inside out, and nearly closed). The machine then descended with great rapidity, oscillating wildly. Two or three hundred feet from the ground, the basket became disengaged from the remnant of the parachute, and Cocking was doomed. His broken body was found in a nearby field.”

My notes: You’d need to get the boffins at the AAIB to pick the bones out of this but, I think, a couple of points can be taken for granted? For example the weight of this apparatus. You could easily parachute an ocean liner, probably with a parachute the size of Bedfordshire? The principal elements being having materials strong enough, fabrication elements strong enough, and enough surface area to provide enough ‘drag’ to defeat gravity to some extent.

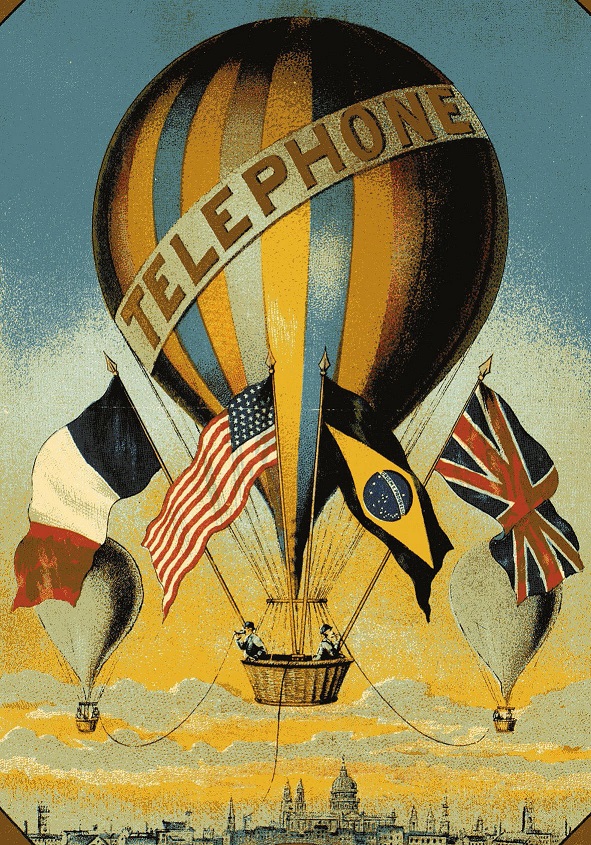

Note: This illustration is clearly an artists impression designed to celebrate the invention of the telephone. The reason for including it here serves to illustrate several points that are pertinent to the period. The 'balloons' are clearly flying to the south of St Pauls Catherdral in central London. A balloon launch, especially in the early half of the nineteenth century was a very prestigious affair indeed, and London was the centre of ballooning in the UK during the entire nineteenth century and this continued to be the case into the early years of the twentieth cenury. Obviously the designer of the illustration wanted to take advantage of this.

Also of interest is that the 'balloons' illustrated are of a gas filled type, possibly using hydrogen as the lifting agent due to the relatively small size of the balloon envelope - coal gas needed a much larger envelope. The last aspect is that with the prevailing winds in this area being west to sou-westerly, a balloon lifting off from VAUXHALL GARDENS would quite likely have been seen in this location - hence it being included here. So, a few facts based entirely on a work of fiction.

CHARLES GREEN

The more I learn about Charles Green the more I admire this man. Why isn’t he a national hero along with Nelson and Wellington? He really did think things through and was so obviously a great pioneer, and surely should be a national hero. Why do we Brits seem to have a skew-wiff idea of what constitutes a national hero? Like preferring David Livingstone to Charles Green for example where, as far as I can make out, the only thing Livingstone was particularly good at, was walking - albiet quite a long way through Africa. Obviously this is a rather unkind appraisal of the accomplishments Livingstone achieved, but I am trying to make a point.

It is claimed that Charles Green made a total of 526 ascents during his career as an aeronaut. In 1836 Mr Green negotiated a deal with Frederick Gye and Richard Hughes, the proprietors of VAUXHALL GARDENS, to perform balloon ascents as part of the attractions on offer. Indeed, balloon ascents, and not just by Charles Green, were a major feature until the venue closed in 1859.

Perhaps the most famous part of Charles Green's involvement was the massive balloon he commissioned, the Royal Vauxhall which stood eighty feet high and used coal gas as the lifting agent. This was often used to give up to nine passengers and ascent to around a hundred feet so that they could view famous landmarks in central London.

NOT ALL PLAIN SAILING

As this tale illustrates: “Meanwhile, Green and Spencer had a narrow escape of their own. At the moment the parachute disengaged they had crouched down in the carriage, Green clinging to the valve-line to permit the escape of gas. The balloon shot upwards, the gas pouring from both the upper and lower valves. The two men were then forced to put their mouths to tubes attached to an air bag that they had had the foresight to provide for themselves, otherwithey would have been suffocated. The gas still managed to deprive them of sight for four or five minutes.”

The tale ends: “When they came to, they found they were at a great height but descending rapidly. They managed a safe descent near Maidstone, Kent, still unaware of the fate of their late companion.” To the last this author seeming totally convinced the solicitor Mr Spencer was having a very proactive part in the proceedings, stating “they” time and time again. This is a common mistake amongst reporters and journalists, thinking that passengers were heavily involved in certain incidents or accidents. Can we get this right for once, a passenger is just that, just a passenger. Having no more influence on the outcome on the actual flight, by and large, than baggage.

A FLIGHT TO GERMANY

On 7th November 1836 the aeronaut Charles Green with two passengers, (Robert Holland MP and Thomas Monck Mason a theatre producer), took off from here at about 13.00hrs to undertake a long distance flight in the ‘Royal Vauxhall Balloon ’. Passing over Canterbury, Dover, Calais and Liege they flew through the night before landing in Germany near Weilburg in the Duchy of Nassau at about 07.00. That is a distance of about 480 miles (772kms) a feat I find even today as being quite extraordinary.

For a full and detailed account of this remarkable and fascinating flight I can highly recommend reading Falling Upwards by Richard Holmes. Not least for the list of food and drinks they took on board to sustain them. After making this flight Charles Green renamed the Royal Vauxhall as the Royal Nassau in honour of the region, north-west of Frankfurt where they landed.

A HIGH ALTITUDE FLIGHT

In 1838 George Rush of Elsenham Hall, (near to STANSTEAD), a wealthy amateur scientist and astronomer, (who developed an aneroid barometer), chartered Charles Green to test instruments in high altitude flight. Remember dear reader, we’re talking 1838 here, not 1938. Their first attempt reached 19,000ft but a later flight seems to have reached 27,000ft. They had no oxygen breathing apparatus on board and by today’s standards it seems remarkable they even survived? But survive they did and held this altitude record for about 25 years.

AN ATLANTIC CROSSING

Even before the 1840s Charles Green had noticed that the prevailing high altitude winds in the UK were from the west. As Richard Holmes quotes in his book Falling Upwards: 'Under whatever circumstances I made my ascent, however contrary the direction of the wind below, I uniformly found that at a certain elevation, varying occasionally but always within 10,000 feet of the earth, a current from west to east, or rather from the north of west, invariably prevailed.'

Mr Holmes also tells us that Charles Green had calculated that a two-thousand-foot guide rope, fitted with canvas sea drags and copper floats, would be enough to stabilise an eighty-thousand-cubic-foot balloon and keep it airborne, without expending additional ballast, for 'a period of three months'. Plus of course, the voyage would have to depart from America.

It appears that, if a generous sponsor could be found, he would undertake a trans-Atlantic flight immediately. In the event he could not find a sponsor and refused to embark without one, so the project was shelved. One can only conjecture that, if a sponsor had been found, the attempt would have succeeded. Without much doubt, if anybody could have made the flight at that period in time, Charles Green was the man for the job.

However, given the knowledge we have today of the often violent weather systems which crop up regularly in the north Atlantic, and the almost complete lack of any forecasting ability at that time, it would appear that the chances of surviving a low level crossing would have been marginal? On the other hand, there was already a great deal of maritime knowledge available regarding conditions likely to be encountered across this ocean at various times of year, so we must wonder if Charles Green had fully studied the subject; given his claim to depart immediately if a sponsor could be found.

We'd love to hear from you, so please scroll down to leave a comment!

Leave a comment ...

Copyright (c) UK Airfield Guide