Wyton flying sites

WYTON: Military aerodrome

Military users: WW1: RFC/RAF Night Landing Ground

75 (Home Defence) Sqdn

RFC (Home Defence) 65 & 117 Sqdns

20 Reserve Sqdn

RFC/RAF Training Squadron Station and Mobilisation Station 1916 to 1919

31 Training Sqdn (BE.2Es)

Location: I had considered that this airfield was pretty much in the centre of the WW2 airfield. But, a member of the VT Aerospace staff serving in 2010 at the present day RAF WYTON and who had researched the subject told me the WW1 site was “Just across the road from the WW2 site.” That’d be the B1090 to the west were there is now a small industrial estate, which seems to fit the general pattern of events?

Period of operation: WW1: 1916 to 1919 (It does seem the site closed for a short period after WW1 in 1920 before re-opening, and bearing in mind the remarks above, is of course still operational today)

Site area: WW1: 151 acres 1052 x 576

WYTON: Military aerodrome later major air base. Now with limited military/civil use

(Now in CAMBRIDGESHIRE)

Note. Pictures by the author unless specified.

Military users: Interwar years: 44 Sqdn (Hawker Hinds)

139 Sqdn (Blenheims)

WW2: RAF Bomber Command 2 Group later 8 Group

15, 40, 114 & 139 Sqdns (Bristol Blenheims)

83 & 156 Sqdns (Avro Lancasters)

No.8 (PFF) Group Comms Flight

1409 (Met) Flt (De Havilland Mosquitos)

Pathfinders: 39, 83, 109, 128 & 139 (Jamaica) Sqdns (Mosquitos)

83 Sqdn are also listed as flying Lancasters

Lancaster Major Servicing Station

Post WW2

1946: 1688 BDTF (Bomber Defence Training Flight) – (Still flying Spitfires?)

44 Sqdn (Avro Lincolns)

1960s: 543 Sqdn (Photo Reconnaissance) (Vickers Valiants & Handley Page Victors)

Note: Initially the Victors of 543 Squadron were the B.1 bomber version.

39 & 58 Sqdns (English Electric PR Canberras)

51 Sqdn (Comets & Canberras, later Nimrods)

1975: (Victors, Canberra’s, Comets & Nimrods)

207 (Southern Communications) Sqdn (Beagle Basset C.1s, Percival Devon C.2s & Percival Pembroke C.1s)

Note: Have I got the period correct for 207 Squadron?)

1980s: 51 Sqdn (Nimrods) 100 & 360 Sqdns, plus 1 PRU & 231 OCU (Canberras)

39 Sqdn (PR Canberras)

100 Sqdn (H.S. Hawks)

2013: Cambridge University Air Squadron and University of London Air Squadron

Grob 115 Tutors

(Both scheduled for moving to RAF WITTERING (NORTHAMPTONSHIRE) in 2014)

Operated by: 2000 - : Still RAF, used for ab initio training served by VT Aerospace Grob Tutors.

Location: E to ENE of junction B1090/A141, E to NE of B1090, S to SE of A141. 1nm N of Wyton village, 3nm NE of Huntingdon. Even a modern Flight Guide book states that this aerodrome is 3nm North West of Huntingdon and these very basic errors, (which really are inexcusable), often plagued my early research when simply trying to find out where really well known aerodromes are actually situated.

Period of operation: Military flying from 1937 to 1985? Civil flying from ?

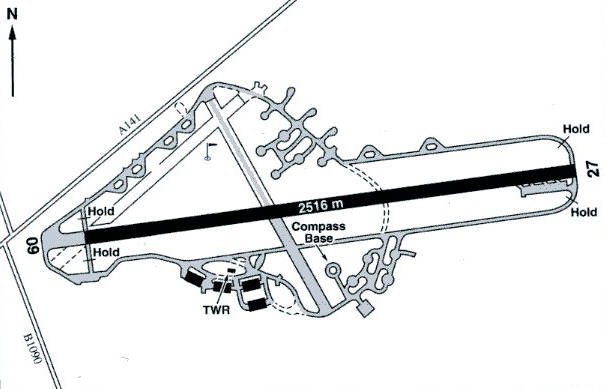

Note: This map is reproduced with the kind permission of Pooleys Flight Equipment Ltd. Copyright Robert Pooley 2014.

Runways: WW2: 09/27 1829x46 hard 05/23 1280x46 hard

16/34 1280x46 hard

2000: 09/27 2516x61 hard

Over-flying WYTON in 2004 I took a few pictures and saw a shorter cross runway being marked up as 13/31? Was this because of the Grobs operated perhaps?

By 2004 another runway had been added on the old 16/34 runway. This was 15/33 760x18 hard, see picture above.

NOTES: This is certainly something to be noted regarding how WW2 started for the RAF, and quoted from The Reich Intruders by Martin Bowman: "At the time of Chamberlain's historic broadcast, (My note: Neville Chamberlain was the Prime Minister at that time and had declared war on Germany), a Blenheim IV of 139 Squadron, piloted by Flying Officer Andrew McPherson (killed in action 12.05.40), was preparing to take off from Wyton. His crew was Commander Thompson RN acting as observer and his WOp/AG Corporal V. Arrowsmith (KIA 24.9.40). A minute later they were airborne heading out over the North Sea to reconnoitre the German fleet at Wilhelmshaven. As they gradually gained height through haze and a freezing mist, which caused the camera and radio to freeze up, they must have had doubts as to whether they would be able to see their objectives. On reaching 24,000ft they flew onto Wilhelmshaven, where Comander Thompson was able to sketch details of the location of the enemy fleet. Finally, after the first operational flight of the war, which had lasted five hours and fifty minutes, they landed safely back at Wyton.

BY CONTRAST

It is of course my self-imposed duty to relate stories in this ‘Guide’ mainly related to flying, but there are a few exceptions I can’t resist, told by aircrew. This is one classic I’d say, told by Joe Patient in his book ‘PILOT’: “One evening a whole party of us climbed into one of the cars to go the George at Huntingdon which had always been one of our favourite pubs. After quite a few drinks we set off home. With so many squashed into the car, we didn’t notice until we were well on our way that Norry was missing. Norry’s tale of that night went the rounds of the RAF and was even told, slightly modified, on the stage by a comedian.”

“This was his story.” ‘When I came out of the George I found the sods had gone off and left me to fend for myself, so I had no alternative but to walk back to camp. By now it was very foggy indeed. I could hardly see two feet in front of me. As the odd car crawled by I tried to get a lift, but to no avail. I became a bit cheesed off with this and when the next one came by I opened the rear door and got into the back without saying anything. I looked around the car and in my sozzled condition was about to make apologies for my intrusion, but found there was no one else in the car, not even a driver. When it came to a corner or a curve in the road, a white hand materialised from nowhere, turned the wheel and vanished. I was getting very jittery and nervous about this and tried to collect my addled thoughts together, but told myself that while it was going in the right direction, I might as well sit tight.’

‘After about twenty minutes of this ghostly journey, the car finally came to a halt at the gates of Wyton aerodrome. I got out and had retreated two or three yards from the car when a squadron leader and flight lieutenant came into sight. “I shay old chaps,” I said with a drunken slur, “don’t go near that car, it’s haunted.” “Haunted be buggered,” said the squadron leader, “We’ve just pushed the bloody thing all the way from Huntingdon.”

'PAMPA'S FLIGHTS'

By comparison he tells of ‘Pampa's’ flights for weather reports for a raid on Nuremburg on the 30th March 1944. “Norry and I took off at 1035 hrs to 5500°°N. 0500°E., after which we reported 4/10ths cumulus cloud over the sea with a cloudbase at 1,660 feet and tops at 9,000 ft. A large amount of cumulus was noted and reported to the north of our furthest position. Landed at 1235 hrs. A further Pampa deep into Germany was carried out by Flying officer T. Oakes (P) and Flight Lieutenant R. G. Gale (NAV/W) taking off at 1200 hrs. They reported seeing only fair weather cumulus throughout their route. These rather mundane flights are mentioned because of their relation to what has been described as the greatest error of judgement in any operation of Bomber Command, resulting in its biggest single loss. It would seem the two reports were discounted because the bombing raid on Nuremburg that night was carried out in full moonlight and with little cloud cover. The results were disastrous. Ninety-five aircraft, (sixty-five Lancasters and thirty one Halifaxes) were lost, with very little damage to the target.”

“Wyton was like a morgue. Never had I experienced such silence, although many stations had suffered greater losses. It is difficult to appreciate that more fully trained aircrew died in that one night than the total killed in Fighter Command during the whole of the Battle of Britain. Following as it did, less than one week after the traumatic flight to Berlin, when seventy-two aircraft were lost..”

IS AN EXPLANATION POSSIBLE?

How on earth could these raids have been allowed to happen? It appears like a wilful and evil act of sabotage. Sometimes in life you have to accept that although appearing utterly ridiculous the only remaining answer, no matter how unacceptable - is in fact the truth. Could it really be true that within the corridors of power, within government, the Air Ministry and especially RAF High Command, they were riddled with Nazi regime moles? Dedicated as far as possible to wreak havoc, death and damage? If so - they were very bold. Today we are told to believe these mostly public school educated people were often utter fools, mindless cretins etc. I refuse to believe this, it simply doesn’t make sense - or does it? The military system spends a lot of effort in making sure that at every level ‘in the ranks’ – orders are mindlessly obeyed, even if they make no sense. And objections from lower ranks are seldom allowed to be heard, before an event taking place.

If you accept my contention that these very senior people knew exactly what they were doing then quite suddenly the proof exists almost everywhere, if you care to look for it. In fact almost the entire bombing campaign appears deliberately organised to inflict maximum damage to our forces. For example just look at the inbound routes chosen as often as not, compared to the outbound routes. Plus of course the insistence of having streams of bombers all following the same route. It is now recognised that experienced crews flew away from the streams to help avoid detection and in some cases pilots retrained as navigators to enhance their chances of surviving!

This didn't just apply to Bomber Command either. In 2015, just before editing and filing this entry, I had just finished reading Spitfire Pilot by Roger Hall, DC. This is a superb book which I would highly recommend as his descriptions of aerial combat are without equal. He tells of being in a Flight which had been given vectors to intercept an incoming enemy bomber force. Knowng that the instructions would put them at a severe disadvantage, the pilot leading the Flight flew on a reciprocal course and turned the Flight around to intercept the top cover Luftwaffe fighters at their level. The results were dramatic - they shot down several Me 109s with no loss to themselves. Having announced this tremendous victory, the pilot leading that Flight was immediately posted elsewhere - destination unknown. It really does make you think what on earth was going on, does it not?

Quite often, even though just a private pilot, I applied the rule of how I would go about it to improve my chances of survival when on a mission, and indeed to protect those flying around me. Invariably I would have adopted entirely different tactics. I would for example never ever group large amounts of aircraft together along a single route. Needless to say the risk must increase enormously when approaching the target but I would at least try to spread the force around before homing in. With the navigation aids becoming available and several countermeasures being developed, surely it was possible to devise fairly simple methods to reduce the risk? For example having echelons coming in from a variety of directions at timed intervals and varying altitudes. Flying a huge heavily laden bomber stream directly over the most heavily defended territory seems utter folly. And, generally speaking, it appears that having reached the target, the bombers could then make their way home by flying over much safer routes. This isn't just opinion, the records exist for anybody to scrutinize.

Perhaps the biggest surprise being that ‘Bomber’ Harris apparently didn’t seem to realise what was going on under his command?

FRIENDLY FIRE

Another common WW2 theme Joe Patient mentions in his book Pilot is the possibility of what is now euphemistically called ‘friendly fire’. To quote from his part in the D-Day landings; “Some of our fighter pilots were not very well up on their aircraft recognition, so there was the ever-present possibility of being shot down by one of our own in the general mayhem." This possibility was reduced in the last few days when all our aircraft had black and white stripes painted round their fuselages and beneath their wings. Another reason for painting ‘invasion stripes’ on the fuselages and wings of allied aircraft was to try and deter Navy and Army anti-aircraft gunners from shooting down Allied Forces aircraft. On another note it appears that the single weather report he and Norry filed on the 3rd June 1944 after a Pampa flight to Morlaix and Vièrge and finding it, “…pretty solid from 18,000 feet down to 500 feet in most places.” - was probably the key factor in the D-Day landings being delayed by 24 hours. He explains, “It was a bit dicey descending to 500 feet when not completely sure of our position, but it was required, so we did it thoroughly."

Conducting these Met flights, or Pampa sorties, was a very dangerous business and many crews were lost. As Air Vice-Marshall Bennett said, “No. 1409 Flight never hesitated for one moment, and never failed to do their job with absolute reliability and consistency. In fact, even when aircraft unserviceability interrupted the flight it was only a matter of minutes before an alternative aircraft was in the air on the same job, or, alternatively, if the unserviceability occurred when the flight was well in hand, it would be completed in spite of the unserviceability. There were harrowing experiences for the crews of 1409 Flight when they were intercepted, particularly by the German jets just towards the end of the war, which could outpace them but not out-manoeuvre them. The anxiety to run for home had to be overcome whenever the enemy closed, so as to take advantage of the Mosquito’s ability to out-turn the enemy.” Just like photo-reconnaissance aircraft these Met Flight Mosquitos were totally unarmed.

COMETS USED?

I will readily admit that until researching this ‘Guide’ I had no idea that a version of the DH.106 Comet airliner was used here (or elsewhere for that matter) by the RAF for photo-reconnaissance duties alongside PR versions of the Canberra, from 1963. These being replaced by the Nimrod (itself a design roughly based on the Comet) in 1974. I had mistakenly thought they were employed just for transport duties at bases such as LYNEHAM.

Mike Holder gives us a small insight into what was involved: "The Comet 2s were the square windowed variety - de Havilland Comet C.2R - and could not be fully pressurised - I think we flew with a cabin altitude of 20,000ft. We spent most of the flight on oxygen which was a bind - no smoking - and our sandwiches used to curl up due to the lack of humidity. The Navs (Radar and Plotter) were opposite the front door facing port on a bench like Nav station. The galley was just to our right which was behind the cockpit with the two pilots and engineer. If the Engineer forgot to puncture the foil cover sealing the NAFFI coffee tins, they used to explode half way up the climb, covering the navs with coffee powder. And I can't decribe the mess, especially on your nav charts and of course over us. Just try tipping a jar of coffee powder over your head and you'll find out."

Not quite the glamorous picture the RAF tried to portray of our finest heroes serving on the front line! It is hard, is it not, to avoid bursting out laughing?

On the other hand, he added this snippet: "We had a Comet 2 hack, an old BOAC Comet used for pilot continuation training. It was still kitted out inside with the BOAC layout. I used to enjoy going on the CT sorties because the nav sat directly behind the 1st pilot; it was wonderful to sit there and stare out of the window and watch the world go by."

He also tells us that: "51 Sqn also used Canberra B6s and 39 Sqn had its PR9s and 360 Sqn had the Canberra T4, B2, B6, T17, PR7 and E15s. Finally 543 Sqn had its Victor 2s for its recce role."

Note: This great picture was kindly provided by Mr Michael T Holder

Mike Holder was a navigator radar and later a navigator plotter on Avro Vulcans before progressing to the Comet 2R and latterly the Nimrod R1, MR1 and MR2. This example, XW664, was a Nimrod R1 of 'R' Flight, 51 Squadron, and the picture is dated 31st October 1973, this being during its inaugral flight.

He tells us that; ".... although based on the Comet, the Nimrod R1, MR1 and MR2 did not fly anywhere near as well due to the addition of the bomb bay structure under the fuselage which caused it to exhibit a continual 'Dutch Roll' which was highly undesirable for its R1 role and certainly was not an asset for the Maritime role. Any yaw on an aircraft puts false drift into the navigation system and calculates a false wind. This affects your weapon aiming system. What you need of any weapons platform is the ability to sit still for 10 seconds while you aim your depth bomb, torpedo or whatever ordnance you are about to launch at your target. The modification of the fin - extending it forward - was supposed to help, and later finlets were added to the rear wing to improve stability (For AAR)."

"Note: the Vulcan had yaw dampers to stabilise it. It was a good steady platform for bombing."

"The Nimrod was practically a clone of the Comet; we had the same four hydraulic systems - the same electrics, fuel systems etc - you only have to look at them to see the Nimrod is a Comet with a bomb bay strapped on and the fin extended forward. In maritime it was known as a "14 man, 4 fan, 14 can, all aluminium, stacks of room in them, hot shit pursuit ship - we're big, we're brown and we're beautiful and on a mission from God and don't you forget it." That's what I told a young USAF lady corporal in Keflavijk, Iceland. She just stood there with her mouth open - that'll teach her to say "What's a Nimrod?" "

THE END OF AN ERA

In 2023 it was announced that RAF WYTON had been formally closed. But it seems, a new grass runway, (08/26 940), had been laid out in 2015.

Philip Noble

This comment was written on: 2020-01-08 06:48:32Between 1951 and 1958. I travelled daily to school from St Ives to Ramsey. Our route via B1090 - A141 junction RAF Wyton. On returning one afternoon, our double decker bus arrived at the cross roads at the same time as the only Lancaster then stationed at Wyton passed overhead as it came in to land.The girls on the lower deck screamed and us boys on the upper deck were counting the stones in the main undercarriage tyres ! Passing over,the bus swayed violently ,but we survived. One week later traffic lights were installed at the junction. I cannot remember the date, but would love to know more about the Lancaster. I am now 80. I was also present at BOB display 19/9/1953, when meteor from 56sqdn broke up in front of me, also at Wyton. Any further information would be appreciated,

Peter Cornelius

This comment was written on: 2020-08-28 09:41:06I joined 543 Valiant PR Squadron at RAF Wyton 10th January 1957 on my return from Operation Buffalo, the dropping of the Atomic Bomb at Maralinga, South Australia. 543 had just returned from a detachment to Goose Bay, Canada. Mine had been the warmer detachment so I was not envious! I was a Corporal Tech. Air Radio Fitter (included Radar). My Flying Log tells me that on April 2nd I was asked to fly in Station Flight Anson19 VM361in order to check Eureka and the B.A.B.s (Beam Approach Beacon.) Via the radar screen I started out by giving the pilot "Left and Right" instructions but he asked for "Dots and Dashes" to interpret for himself. We achieved the objective but then made a hasty return when an engine blew a plug. At least we didn't need to do a wheels-up forced landing as I had on my first ever flight, as 16 year old in Anson22 VV366. In May 1958 543 had a month long Exercise "Sunspot" to Luqa, Malta. I recall that one exercise was for photograph all the naval ships which had dispersed into the Mediterranean. This was achieved with photographs of all ships through cloud, apart from one ship which had returned to Valleta due to problems, and the arircrew had not thought to look there! July 17th 1958 I few by DH Comet (first jet aircraft flight - so comfortable) as far as Changi, Singapore, and then by Hastings to RAAF Edinburgh Field, South Australia, landing on the 23rd. There just a month while servicing a single Valiant from 543 as it photographed the Woomera Rocket Range in preparation for "Blue Steel" stand-off bomb trials. While at RAAF Edinburgh Field I noticed a Hastings looking deserted outside a hangar, and learned that it was awaiting a major service, which apparently the RAAF could not provide. Our small detachment were destined to fly in that Hastings for our return to RAF Wyton. With engines out of sync. it was amost unpleasant flight. Staging, amongst other places, at the high airfield of Eastleigh, Kenya, the pilot needed to "go around" after his first attempt to land. The flaps would then not retract so the "go around" was with engines roaring away in the thin air in order to counteract the drag of the flaps. At least a day in Nairobi, while the flap problem was sorted, meant that the RAF provided a rear-caged lorry for a tour of the wild life park. The continuing flight over the mountains of Africa. with many sharp "air pockets" meant almost all we passengers were sick, so much so that one passenger was dropped off at our final staging post at Idris. (I recall on one of the "air pockets" we had just been supplied with coffee in 'plastic' beakers. When the aircraft dropped the beakers came with us, but not the coffee! Suspended in the air above us was coffee in the shape of the beakers. At the bottom of the pocket we all ended up with coffee soaked laps. On 26th September 1958 I was promoted to Sergeant and moved into the Sergeants' Mess. I also left 543 Squadron and was moved to supervise 2nd Line servicing of Valiants in the hangar. That was 'short lived' as on May 30th 1959 I was posted to RAF Marham. I was sorry to leave such a happy station and would have been more so had I realised that I was going to finish my RAF time at such a low moral, unhappy station. On December 2nd I was flown in Anson19 VM324 to RAF Hemswell to deliver some radio equipment.

We'd love to hear from you, so please scroll down to leave a comment!

Leave a comment ...

Copyright (c) UK Airfield Guide