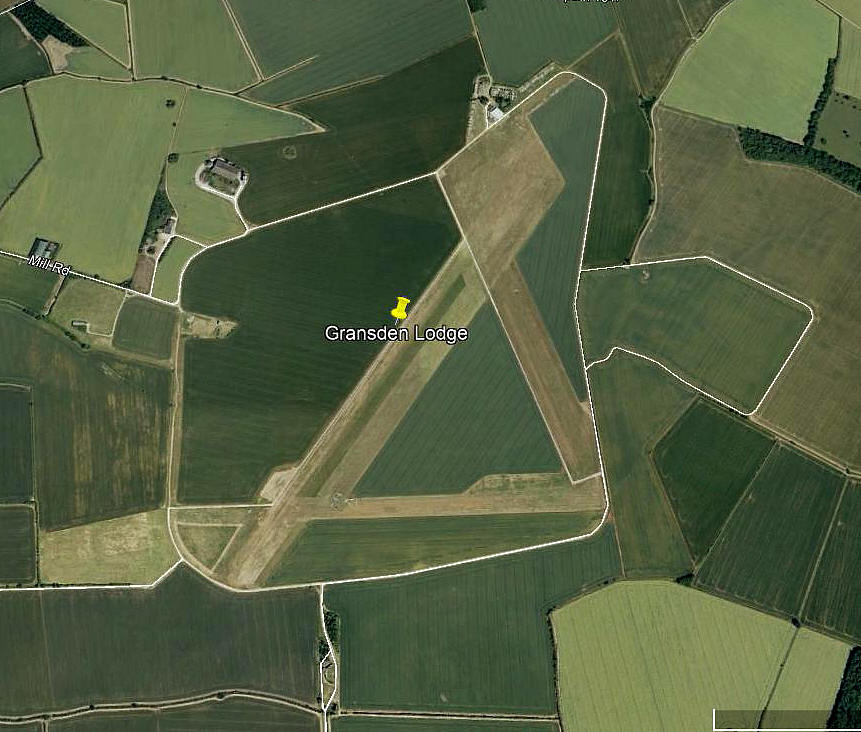

Gransden Lodge

GRANSDEN LODGE: Military aerodrome later civil gliding site (Now apparently in CAMBRIDGESHIRE)

Note: This picture was obtained from Google Earth ©

Note: Picture by the author who was more intent on photographing the GA airfield Little Gransden seen in the foreground. The main reason for not getting closer to GRANSDEN LODGE is that, quite rightly, the gliding fraternity take a dim view of light aircraft busting through their area of operations without permission, and we didn't know if they had a radio frequency in use.

Military users: WW2: RAF Bomber Command 8 Group

1474 Special Duty Flight (Vickers Wellingtons)

142 Sqdn (DH Mosquitos)

405 (Royal Canadian Air Force) Sqdn (Avro Lancasters)

Bomber Development Unit (Avro Manchesters, Handley Page Halifaxs & Avro Lancasters)

Location: E of Little Gransden & NW of Longstowe villages, 9nm W of Cambridge

Period of operation: Military 1942 to 1955 then much later gliding site to present day

Runways: WW2: 03/21 1829x46 hard 17/35 1280x46 hard

10/28 1280x46 hard

NOTES: Although having the bog standard runways and hardstandings for 36 heavy bombers the fact that in 1944 ‘only’ 1111 RAF personnel, (including 275 WAAFs), were listed here seems to indicate this airfield was possibly still being used for more specialised operations? In fact it appears that specialised operations were a feature of GREAT GRANSDEN throughout much if not most of WW2.

SPECIAL OPERATIONS

As mentioned elsewhere in this 'Guide' these specialised operations were often incredibly dangerous and it seems a shame that far greater recognition is generally not afforded to these aircrews. Take this example given by John Sweetman in his excellent book Bomber Crew. I trust you’ll agree it is well worth giving the account from 1942 in full: “The airborne radar carried by enemy night fighters remained a puzzle. Until more details were known, no effective counter-measures could be fashioned."

AN EXAMPLE

In the early hours of 2 December, therefore, a specially equipped Wellington from No.1474 Special Duty Flight took off from Gransden Lodge near Huntingdon with extraordinary, and for its crew potentially fatal, orders to allow a night fighter to close in, all the time radioing information about its radar emissions and performance. Once this had been done, the crew could make its escape – if still possible. The Flight’s ORB (My note: Operations Record Book) noted that ‘the aircraft was engaged on the eighteenth sortie on a particular investigation, which necessitated the aircraft being intercepted by an enemy night fighter, and up to this sortie all efforts to get such an interception had failed.”

Incredible isn’t it? Many people, especially some historians, seem to get quite upset at the suggestion that RAF aircrew sometimes embarked on missions which were clearly suicidal and although I accept this in terms of ‘intention’ I find it a damned fine line to distinguish the difference between ‘intention’ and ‘expectation’. To my mind crews embarking on missions such as this crew performed were incredibly brave.

But when you read their accounts, virtually to a man they would deny this. They point out that in a war, when your nation is fighting very hard just to survive, the concept of self-preservation has to be put way behind the call of duty, the willingness to follow orders and a patriotic ideal to sacrifice oneself to enable your nation to survive. Regarding the latter, by 1943, it was by no means a guaranteed outcome of course.

“Shortly after 4.30 a.m., near Mainz, the special radio operator, Pilot Officer Jordan, picked up faint signals, which increased in volume as a fighter came closer. He warned the crew to expect an attack and drafted a message for the wireless operator, Flight Sergeant Bigoray, to transmit, it being ‘absolutely vital that this information’ – and particularly the frequency of the incoming signal – ‘should reach base at all costs’.

‘Almost simultaneously the aircraft was hit by a burst of cannon fire. The rear gunner gave a fighter control commentary during the attack and indentified the enemy aircraft as a Ju 88’. While the pilot, Sergeant Paulton, corkscrewed, although hit in the arm Jordan drafted another message confirming the frequency of the fighter’s airborne radar. At this point, the rear turret malfunctioned and the gunner was wounded in the shoulder during a second attack in which Jordan was hit in the jaw. ‘But he continued to work his sets and log the results and told the captain and crew from which side to expect the next attack’.”

“The front turret was then disabled and the gunner (Flight Sergeant Grant) wounded in the leg. As the wireless operator (Bigoray went forward to help Grant, an exploding shell wounded him in both legs and he had painfully to return to his seat. The Ju 88 could not be shaken off, but Pilot Officer Barry (the navigator) managed to free Grant. Jordan now suffered an eye injury, and he realised that he could not continue with his work much longer. With his intercom connection shot away, he had physically to fetch the navigator to help him. However, Jordan was effectively blind and was forced to ‘give up the attempt to show Barry what to do’."

"Meanwhile, Flight Sergeant Vachon had moved from the useless rear turret to the astrodome from which he ‘could give evasive control’ until wounded once more, whereupon Barry replaced him. Durng all this chaos, the aircraft had plunged from 14,000ft to 500ft, with ‘violent evasive action still being taken by the captain’. To his and his crew’s relief, after an estimated twelve attacks, the fighter broke away, leaving the Wellington heavily damaged and four of its six crew seriously wounded. Fortunately, the pilot was not one of them, but his aircraft was certainly in a bad way. The port engine of the twin engine machine had its throttle shot away, that of the starboard engine had stuck. Both engines were therefore misfiring, and both gun turrets were out of action. Added to these calamities, both airspeed indicators, the hydraulic system and the starboard aileron were useless. The prospect of reaching England looked decidedly slim.”

“Paulton did, though, nurse his perforated charge gently over the Channel, and at 7.15 a.m. the Kent coast appeared ahead. He decided that it would be unwise to attempt a conventional landing, so opted to pancake on the sea inshore. Bigoray’s injured legs were a problem. The wireless operator had the best chance of survival if he used his parachute, so Paulton flew over land before turning out to sea again. Bigoray duly made his way painfully to the rear exit, before he realised that he had not locked down the morse key so that the position of the aircraft could be traced. He went back to his post to do this before baling out with copies of his signals in his pocket in case they had not been received. Paulton put the damaged Wellington down on the water off Walmer. He and the rest of the crew then clambered into the dinghy only to find it so badly holed that they had to splash their way back to the wreckage and cling on until a small boat rescued them.”

And here comes the punchline! “The Flight report sparsely recorded: ‘Aircraft sank. All crew safe’.”

This incredible story needs no extra comment from me of course. But, on a more general note the Wellington, with its geodetic fuselage structure designed by Barnes Wallis, was renowned for being able to absorb a colossal amount of combat damage. Which begs the question, why wasn’t geodetic construction adopted for later aircraft designs, especially bombers? I’m sure somebody can answer this?* Also, does this almost singular ability explain why, although the Wellington first flew in June 1936, the last example rolled off the producton line in October 1945. See HAWARDEN in FLINTSHIRE for info on the Wellington LN514 built in less than 24 hours – and flown in just over 24 hours.

*In September 2021 I was kindly contacted by Mr Andrew Miller who explained that according to his understanding, the geodetic method of construction flexed too much to be clad in metal and therefore fabric had to be used. And, fabric on major structural components is useless above 300mph.

IN LATER TIMES

In 1985 GRANSDEN LODGE was listed as being used only for agriculture so presumably the gliding activity developed later?

N Perry

This comment was written on: 2020-06-10 19:44:02692 Squadron Mosquito were based here 04 June 1945 till disbanded 20 September 1945. 53 Squadron based Dec 1945 till March 1946 using Liberator transports.

We'd love to hear from you, so please scroll down to leave a comment!

Leave a comment ...

Copyright (c) UK Airfield Guide